Do you know how to pick a good stock? In the unlikely case that you answered yes to that question, then I've got another one for you: are you among the less than 4 percent of stockpickers that will beat the market over a span of 50 years? If it's a yes to that one, too, then I congratulate you and wish you well in your burgeoning career as a high flying money manager. If you're among the vast majority of those that answered no to both, don't worry – we can still make you a millionaire by 60.

Of course, there are many routes that theoretically lead to big money – clamor your way up the corporate ladder, join a pyramid scheme, murder your brother and marry his wife – but if you're like me, you prefer the method that doesn't require any work or bloodshed. Luckily, a fella named John Bogle invented a thing called an “index fund” just for guys like you and me.

What's an index fund?

An index fund is a mutual fund or exchange-traded fund (ETF) that tracks the movements of a stock market index. You've heard of stock market indices: Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJI), Nikkei 225 (N225), Standard & Poor's 500 Index (S&P 500) and the FTSE 100 (“footsie”), for example. An index is meant to provide a snapshot of a market sector's performance. In most cases, the media cites indices to report on the overall health of the economy. We all know that a headline reading “Dow Jones down over 500 points” translates to “We're boned!” whereas “Dow Jones up a bajillion percent” means “Drinks on me!”

The stocks that make up an index are typically picked by committee (subjectively) or by a set of rules (objectively). The S&P 500 is composed by committee, with analysts picking the 500 stocks that they believe best represent certain industries based on the GICS. For example, Tyson Foods is included in the S&P 500 representing the “consumer staples” sector while Microsoft is included representing “information technology.” The Russel Indexes, on the other hand, are selected based on objective criteria, with the Russell 3000 Index being composed of the largest 3,000 companies in the U.S. by market capitalization (estimated value of a company by multiplying the share price by the number of outstanding shares).

A mutual fund is, essentially, a pile of money collected from various investors (you and me) and given to a money manager who chooses which stocks to buy. Most mutual funds have clearly delineated strategies and target certain sectors. Basically, instead of your investment being at the mercy of one stock's gyrations, you are spreading your bets over several stocks. But really, you are simply betting on the man who is managing your money. And you're paying him hefty management fees for it, too. Which is fair, really – that guy (or group of guys and gals and sometimes robots) have to pore over pages and pages of research and cut through all the corporate PR bullshit to find the healthiest stocks. The name of the game is “beat the market” and it's hard work. It's estimated that fewer than 20 percent of mutual funds outperform the market each year.

By now, you've probably figured it out. If the Wall Street kids are reinventing the wheel and still losing to the market, why not just invest in the market? That's what an index fund does. Instead of busting duff to sleuth out stellar stocks, an index fund simply plunks money down in the stocks that the thinktanks at the likes of Dow Jones and S&P have already spotlighted. And because most of the hard work is already done, the management fees are bargain bin affordable while the investment is nest egg reliable.

Wait, reliable? Really?

Believe it or not, yes, index funds are a safe bet. I know that the news is constantly sounding the alarm on market dips and, yeah, we've had a recession, depression or crisis here and there, but historically, the market has steadily been on the up and up.

For example, Vanguard's 500 Index (based off of S&P 500) has returned 9.84 percent since inception in 1976. (Compare that, also, to the highest savings account percentage I've ever seen: 3.00 percent.) As long as you are in this for the long run, you have virtually nothing to worry about. Of course, you'll want to diversify to some degree (there is the old advice: “own your age in bonds”) but if you can spare $83 bucks per paycheck (paid bi-weekly, that's about $2,000 a year) you can be well on your way to being a millionaire by 65 (60 if you start early).

Punch some numbers into Fidelity's Growth Calculator and see for yourself:

- Start with an initial balance of $10,000. (Optimistic, maybe, but hopefully someone's been saving on your behalf.)

- Contribute $2,000 a year. (Depending on how you do this, it's tax free.)

- Invest in an index fund at about a 9.00 percent rate of return. (Like the aforementioned Vanguard 500 Index)

- Let it stew for 40 years. (Beginning at age 20 and investing until 60)

- Come out with $1,050,678

Now, of course, there's other factors to think about, such as taxes, management fees and inflation, but you get the idea. Play with the numbers a bit and you'll notice that:

- The sooner you start, the more you'll make. (Einstein called compound interest the “most powerful force in the universe,” only half-jokingly.)

- The more you begin with, the more you'll make.

- Even a small contribution – especially made early – will make a sizable difference to the final number.

Even when times are tough economically, it's well worth it to squirrel away as much as you can. Those nickels and dimes that might buy you a pounder of PBR today can snowball into a comfy retirement tomorrow.

Getting Started

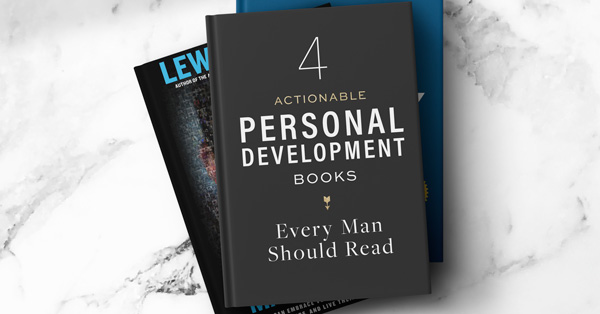

There are a couple different routes to investing in index funds. Most of them are as easy as visiting a site that offers them and signing up, just like you'd sign up for an online checking account. Top dogs in this field are Fidelity and Vanguard. (You'll need about $3,000 to $5,000 to begin investing, though.) Once you sign up, you'll notice that there are a lot of funds to choose from. They'll provide some stats for you, but I recommend the following reading:

- CNN Money's Best Mutual Fund's List

- Best and Worst S&P 500 Index Funds by Cost

- Motley Fool's Vanguard's Best Funds

- Vanguard vs. Fidelity from Battle of the Brands blog

- Picking The Right Index Fund from Forbes

- Index fund article from MarketWatch

The other way to get into index funds is to buy them like stocks. That's what exchange-traded funds (ETFs) are: funds that are listed on the stock exchange. To do this, you'll need to set up a brokerage account. Popular online brokers include:

You can also buy stocks through Fidelity and Vanguard. To understand why you might invest in ETFs instead of an index fund (or vice versa), check these articles out:

- Investopedia's ETFs vs. Index Funds.

- Motley Fool's 60 Second Guide to ETFs

- This piece from MarketWatch on Warren Buffet's endorsement of index funds.

- ABCs of Investing's guide on ETFs vs. Index funds.

So there you have it. As you can see, the prospect of investing in index funds opens an even bigger can of worms. But the takeaway lesson is this: start investing now. And by investing, I don't mean gambling by day trading or hopping on phony trends. I mean picking a reliable strategy – like investing in index funds, for example – and sticking to it. Trust me. You're future self will thank you.