You’ve found yourself in front of a wall of hooch and you’ve got no idea which way is up or down. You’re wondering what the difference between the $200 bottle and the $40 bottle is and can’t make heads or tails of any of the words written on any of them. We’ve all been there, but for me knowing every word on those bottles? That became a challenge, as did how they were made, and the histories behind each one.

In my past 15+ years of bartending, I’ve accrued awards, certifications, and diplomas in alcohol from all over the world. I’ve done all the legwork and I’m here to help you navigate the wonderful world of booze and make you more comfortable in front of that ever-expanding and confusing wall of juice.

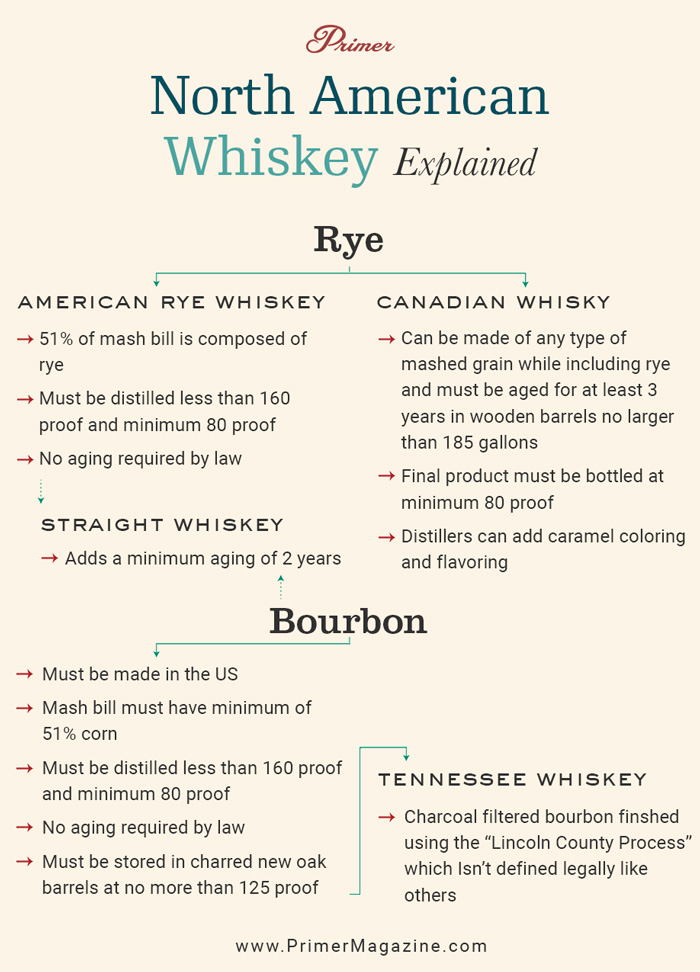

For our first discussion we’re going to dive into the wonderful world of North American whiskies and what makes them unique, fun, and delicious. We’re going to focus on three main types of whisk(e)y: Bourbon, American Rye, and Canadian. But, let it be known that these aren’t the ONLY types of whiskies made in North America, and maybe we’ll eventually talk about the rest, but for today we’re focusing on the big three.

Bourbon

In 1792, when Kentucky joined the Union, people had already been experimenting with distilling corn, but as more immigrants moved into the Ohio River Valley, where corn is especially plentiful, they brought their distilling knowledge and techniques of their home countries. By the 1820s the name ‘bourbon’ had already been attached to the whiskey made in the region, but it’s not until 1835 that bourbon as we know it became the forefather of how we still define it to this day.

In 1823 a Scottish chemist-physician by the name of James Crow moved to Kentucky and began distilling for the Pepper family. Dr. Crow began closely investigating a method of using the spent mash (that’s the gunk left over from distilling) to add to the next round’s grain mixture to help get it to turn to alcohol. This technique is now known as Sour Mashing and today is utilized almost universally throughout the bourbon industry.

While Crow certainly didn’t invent the method (as some marketing teams would have you believe), his scientific background lent to him refining the technique and, by the mid-1930s, essentially birthing modern day bourbon.

James Crow's name on the label of Old Crow

There are many sad truths about the alcohol industry, one is that (almost) no matter what spirit you’re talking about, the reason it is the way it is and tastes the way it tastes is often more to do with legislation and taxation than traditions (remember this as we move forward), and bourbon is no exception.

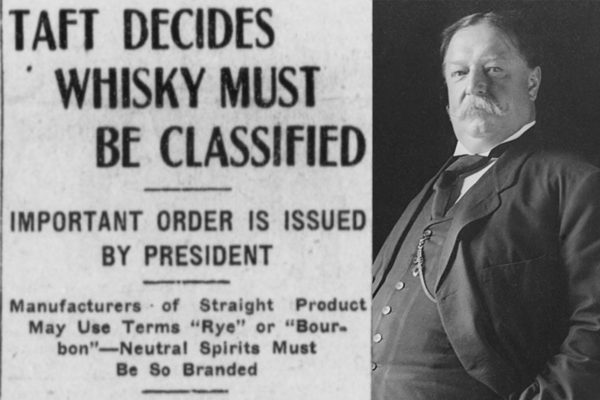

In 1906, the novel The Jungle was published by Upton Sinclair that forever changed the world as we know it. Sinclair exposed the nauseating conditions within the meat-packing industry, and it led to the creation of the Pure Food and Drug Act in the same year. Many distillers began labeling their products as ‘Pure Whiskey’, while others were forced to label themselves as ‘Imitation Whiskey’ due to the new laws.

In 1909 tempers had boiled over on both sides of the debate and President William Howard Taft was forced to step in and define what a whiskey, and bourbon, was.

His decision was amended in 1938 to include that all bourbon must be made in new oak barrels, and again in 1964 to state that it is purely a product of the United States (not just Kentucky), but otherwise Taft’s ruling on what a bourbon is remains standing to this day defining it as a product:

- Made from at least 51% corn,

- distilled no higher than 67.5% Alcohol By Volume (abv) and cannot be bottled lower than 40% abv,

- for it to be labeled as “Straight” it must be at least 2 years old

- and, although it can be watered down, it must be unadulterated with no added colors or flavors.

Bourbon can be a divisive subject when it comes to suggestions on how to use it in a cocktail. Bourbon didn’t enjoy much success until after Prohibition, so was left in the dark when cocktails had their first Golden Era. Bourbon almost always leans sweet due to its high corn content, especially compared to other whiskies, I feel it best shows itself in modern classics such as the Paper Plane or Four Horsemen.

If you’re looking for a slightly obscure classic I’d recommend dabbling with the Boulevardier Cocktail (be careful, as this is sometimes thought of as a ‘Bourbon Negroni’ which always ends up as a disaster in the glass), and it’s always what I reach for as my preferred pour for a Whiskey Sour.

Settle in: Check out Primer's Playlist: Music to Sip Whiskey to: A Gentleman’s Introduction to the Blues

American Rye Whiskey

This might come as a surprise to many, but the earliest spirits distilled in the American colonies were gin, brandies and rums. Early Dutch settlers to New York, then Fort Amsterdam, brought with them the traditions surrounding genever (an early form of gin) production brandies that were made using a process of distilling that involved freezing cider, and New York had 16 rum distilleries within the city by 1720, who mostly smuggled their molasses from Martinique.

But, the combination of many factors left a void to be filled in the nations spirit production: the end of the Revolutionary War, the opening of the Erie Canal (which provided better access to grain from the distillers in the northeast), heavy pre-war taxation on molasses products, as well as Scottish and Irish settlers bringing their distilling techniques into Pennsylvania and Maryland’s rich rye grain belt saw rye whiskey become the United State’s first born-and-bred spirit.

Even George Washington had a more-than-modest rye distillery set up at his Mount Vernon residence producing over 41,000 liters annually.

Rye became important to the farming communities east of the Appalachians, they were able to distill and preserve any of the excess grain from their harvest, as well as spirits, and weren’t prone to spoilage while transporting through the mountains to sell to the Eastern States. Reeling from the financial toll of the Revolutionary War and realizing that a self-supporting and effective government isn’t cheap, Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton began to take notice of the massive economic impact the whiskey trade was having.

Hamilton proposed an excise tax on whiskey produced in the United States, and the farmers of Pennsylvania were outright hostile to the idea, feeling the tax was an abuse of authority that unfairly targeted those west of the Appalachians who relied on crops as a livelihood (those in the east were mostly large scale farmers who could afford the tax and didn’t have to cross a treacherous mountain range to get their goods to major cities; and tax breaks were provided based on producing more).

Whiskey Rebellion

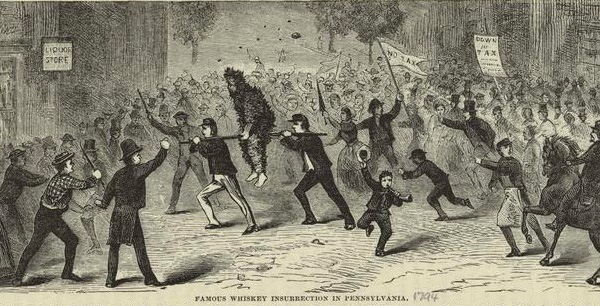

An illustration from 1880 depicting a tarred and feathered tax collector as a part of the “Famous whiskey insurrection of Pennsylvania”

Things go south quickly in 1791 when a tax collector in Washington County is tarred and feathered. Over the next few years the Whiskey Rebellion, as it became known, became more aggressive and demanding, forcing George Washington to march a militia to Western Pennsylvania to stomp out the rebellion.

When the rebels, most of them poor farmers, saw the soldiers they immediately surrendered without any casualties.

George Washington surveys his militia in Maryland before marching toward Western Pennsylvania to suppress the Whiskey Rebellion

Bourbon wasn’t the only thing affected by the Pure Food and Drug Act, as once the act passed, Maryland’s whiskey production ground to a halt as it was mostly rectified, pure spirit with flavoring agents added, leaving Pennsylvania rye (often referred to as Monongahela Rye) to reign supreme.

And, as with bourbon, rye can owe its definition to President Taft’s 1909 decision that defined it almost exactly as bourbon, with the exception that it must be made from at least 51% rye, not corn, and isn’t limited to production within the United States.

Unfortunately for rye, after prohibition hit the US people’s tastes had changed and most of the people now demanded bourbon as their whiskey of choice.

Where bourbon is sweet due to its corn, rye is spicy thanks to its rye. Rye is making its resurgence, fueled by the demand for true classic cocktails such as the Manhattan, Red Hook, Sazerac, or Old Fashioned cocktails where it’s spicy, big bold nature shows best as a base for many of the classic whiskey cocktails that have been enjoyed for generations.

Canadian Whisky

Oh, Canada! The land where rye is “rye” even when it’s not rye… It gets very confusing. But, let’s start at the beginning.

Canada, much like its southern neighbor, was almost certainly not making whiskey in its earliest days. In fact, one Mr. James Grant is shown to have a rum distillery that was outputting over 1.5 million liters annually by 1797. Canada’s rum production was already booming going into the 19th century, however, reports started to surface that residents west of York had begun to distill their excess grain into rye. The government at the time supported these endeavors and encouraged the practice to the point where there was one licensed distillery for every three hundred residents in Upper Canada at the time, it was not long before that Irish and Scottish settlers plied their trade and helped launch the beginnings of commercial distilling in Canada.

The success of Canadian whisky (that’s without the ‘e’) is owed, at least partially, to the strife of other nations. During the Napoleonic Wars, there were frequent brandy and wine shortages in England. Canadian whisky, helmed by the famous Molson family, had already become well known for its quality, and the output of Canadian distillers was far greater than that of any scotch producer at the time.

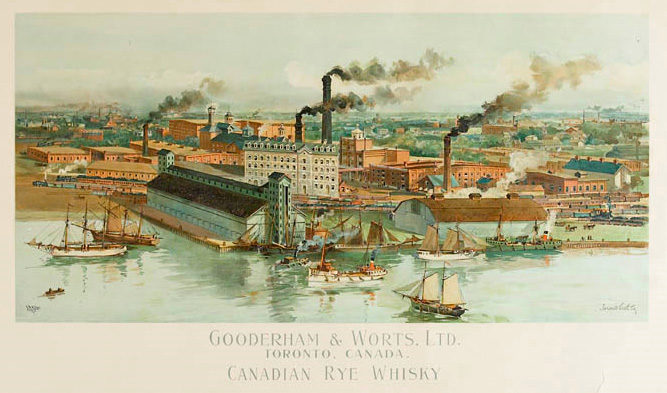

Shortly after the City of York was renamed Toronto in 1834 members of the Gooderham & Worts family began distilling operations in the city. In a time of deep recession, they were challenged to build the greatest distillery the world had ever seen. It took some time but by the end of the century, Gooderham & Worts distillery was the largest in the world. The distilleries two massive pot stills were able to produce over 7.5 Million liters of whisky annually and the entire operation is credited with being a major part of Toronto’s transition from a backwoods outpost to an industrial center.

The Gooderham & Worts distillery in Toronto

The timing of Gooderham & Worts' success, along with the operations of Seagram and Walker could not have come at a better time, because as the Canadian whisky industry was just hitting its stride, the taps were about to run dry in the south.

By the time Prohibition was enforced in the US, hundreds of millions of dollars of whisky began pouring across the border to quench the thirst of Canada’s neighbors.

Unfortunately for the Canadians, there is no Taft character in their whisky story, so the laws on making Canadian whisky are a fair amount looser than those of their Southern counterparts.

For instance, in Canada, you can legally add 9.09% of imported liquor into the whiskey and still call it Canadian whisky. This rule is a tough pill to swallow for a lot of self-prescribed whisky connoisseurs who define themselves as traditionalists, but it’s a practice that’s used in many whisky-producing communities in more roundabout ways. The true talent in Canadian whisky is that of blending, in places like the US the different grains are added together before they’re distilled, whereas in Canada generally grains are all distilled separately and then blended together after distillation.

Canada’s blended whiskies are well sought after for their quality around the globe, and although many whiskies can be primarily made of corn, barley, or wheat, Canadian whisky is almost ubiquitously referred to as “rye” whether the whisky contains any.

Let it be known that the ryes that Canada does produce are some of the best in the world and many distillers in the United States actually contract Canadian distillers to make rye for their American brands.

Because Canadian whisky can be such a chameleon, it can be hard to lock down just what type of cocktails it works best as a category. It can fill the void in many situations depending on the nature of the whisky. Bolder offerings like Lot 40 Canadian Rye can make a fantastic Manhattan, whereas something with a bit less spice and a bit more sweetness, like Gooderham & Worts, works great in a whisky sour.

Drink, enjoy, and be merry.

![It’s Time to Begin Again: 3 Uncomfortable Frameworks That Will Make Your New Year More Meaningful [Audio Essay + Article]](https://www.primermagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/begin_again_feature.jpg)