A Morning in September

It’s a Tuesday in September 2001 and Michael Hingson, the Mid-atlantic sales manager for a Fortune 500 computing company, is prepping for a corporate training session with his colleague David. Michael’s the head of the New York office, overseeing seven employees. Their office on the 70th floor of Tower 1 offers a stunning view over lower Manhattan, the Hudson River, and New Jersey. It’s a thoroughly typical, normal day at work. For now.

8:46 AM: a muffled explosion. The building shudders. Michael and his colleagues begin to realize something is terribly wrong. Debris is falling past the windows outside. They have no way of knowing an airliner has slammed into the North Tower 25 floors above them. Suddenly, Michael is a typical office worker thrust into an extraordinary, terrible situation: the worst terror attack ever on American soil.

Except Michael isn’t typical at all.

Amongst the many extraordinary people in the World Trade Center towers on 9/11, Michael stands out because he’s totally blind. And amongst the many heroes from that day Michael is exceptional because of what happened next.

Michael’s co-worker David starts to panic. Michael tells him, “we’re going to get out, but we need to do it an orderly way.” Michael guides his coworkers to an emergency staircase and leads their descent to safety as the stairwell fills with choking smoke. At the 30th floor, he’s met by NYFD firefighters and declines their assistance so they can help others. As he descends, floor after floor, other panicked people see Michael, calm and encouraging, and follow his group to safety.

Michael Hingson is an American hero. But he’s something more. How exactly did a blind man caught in the North Tower of the World Trade Center not only save himself, but help save so many others? What was different about Michael from those who succumb to panic? What hidden aspects of his past, personality, and skill set enabled him to do what he did?

He’s an example of remarkable, improbable leadership in crisis. What can you and I learn from Michael about how to be a leader in an emergency? What does he teach us about being an everyday hero, every day?

What Stops Good People from Stepping Up?

In order to unpack the lessons Michael has to teach us it helps to realize, in many ways, his situation wasn’t so unique. Most of us will never be in a disaster on the scale of 9/11, but just about all of us will come across a situation where people are injured, panicked, in need, or worse. “The chance of encountering some sort of emergency situation in our lifetime is guaranteed,” says Jerry D. Smith Jr., Psy.D., “and how one responds or does not respond, may mean the difference in life or death to someone you care about or yourself.” Smith is a licensed psychologist and consultant who has spent the last 15 years working with law enforcement as a first responder to emergencies ranging from hostage situations, federal prison escapes, and bomb threats to hurricane response. His message: whatever form it takes, you will encounter a crisis large or small, and probably not where you expect. “Most emergency situations will occur either at or near your home or work place,” says Smith, “where there is not a trained professional on hand.”

Emergencies happen. They will happen to you. And if you’re like most people you’re probably OK with that – at least, in the abstract – because you assume you’ll act appropriately. In our culture, we love to watch action movies starring a hero who does the right thing every time, no matter the personal cost. If you ask most people they’d probably say they share those same action-hero values. Aliens invading? Sign me up. Killer earthquakes ravaging the west coast? I’ll co-pilot for my buddy Dwayne Johnson. But what happens when you see a homeless man fall in the street? Do you help him up?

The problem with our hero narrative is many people simply don’t step up. And I’m no exception.

I lived in New York City for ten years. Nearly every summer, someone would collapse on the subway or sidewalk in front of me. It was often an older person who simply got overheated. So what did I do?

I froze. For a split second, I did nothing. Then, I’d look around to see if someone else saw what happened and was stepping in to help. Then – and only then – I’d move to assist the person. Sometimes I got to them first. Often, however, my few moments of hesitation meant someone else stepped up and I could hover at the edge of the incident, looking concerned, but doing nothing. I’m not proud of my response. I’m also not unique. The question is, what stopped me? What causes that voice in your brain to say, “someone else will handle it,” or “I don’t want to get involved,” or “I don’t think I can help here?”

It turns out psychologists have a name for what causes that voice: the Diffusion of Responsibility. “Simply stated, Diffusion of Responsibility suggests the more witnesses to an emergency, the less likely someone will act,” says psychologist Jerry Smith. It explains why people don’t act in the face of obvious wrong or crisis: they assume someone else is responsible, and do nothing.

The Diffusion of Responsibility can lead to a related phenomenon called the Bystander Effect, a documented social phenomenon in which a group of people don’t come to the aid of a victim in the presence of others, despite witnessing extreme suffering. “I have seen civilians stand around looking on while a seemingly random stranger walked up and started assaulting another man in front of a young boy,” Smith told me, “but the classic example is the Kitty Genovese murder in New York City in 1964.”

Kitty Genovese was 28 when she was raped and stabbed to death outside her apartment building in Kew Gardens, Queens. At the time it was reported 37 or 38 witnesses either saw or heard the brutal crime and did nothing. An unidentified neighbor was quoted as saying, “I didn’t want to get involved.”

Subsequent reporting has revealed far fewer people saw or heard anything than originally reported and that two people did eventually come to Kitty’s aid, but it’s hard not to wonder: if someone had taken decisive action, could she have been saved? The police were called – twice – but they wrote it off as a domestic dispute, in effect saying, “let them sort it out.”

If your response to the Kitty Genovese story is, “That should never happen again,” you’re in good company. The question is, what can you do to ensure it doesn’t happen, at least not on your watch?

Lessons from a Blind Guy

Showing leadership in a crisis can take many forms, but all action starts with acknowledging a single, simple fact: you can make a difference.

I spoke with Michael Annese, a fire Battalion Chief and author with over 20 years of experience in emergency services, who reminded me of Todd Beamer, one of the passengers on hijacked Flight 93 on September 11 who fought back against the hijackers. “In the midst of that chaos he took action, got others involved, and made a huge impact,” says Annese. “He wasn’t some ex-Green Beret. He just decided that was not going to happen in front of him.”

Research has shown leadership starts with your belief in your own ability to help. “Humans have an instinctual urge to fight a threat or try to flee from it,” says psychologist Jerry Smith. “A major factor that contributes to which instinct will win out is how competent that person believes themselves to be to respond to the situation, compared to other bystanders.”

So how do you rate your competency? Chances are, you’re undervaluing your capacity to lead in emergencies. Our assumption is leaders are like artists: either you’re born with the genius to be steady in crisis or not, but that’s simply not the case. Countless examples show untrained non-professionals can respond; guys like you, me, and Michael Hingson, the blind computer salesman caught in Tower 1 on 9/11.

At first glance, Michael is an unlikely leader, but that’s exactly why his story is so damn useful. Peer a bit closer and you’ll see he was, in fact, uniquely qualified to lead a group of panicked evacuees 50 stories to safety. There are three actions Michael took before and during 9/11 that allowed him to do what he did. The first is obvious, unglamorous, and utterly important: preparation.

As he tells it, “When I first went to work at the WTC, I was the one and only blind guy in the office. I spent a lot of time thinking about – what am I going to do in an emergency? What if I’m there alone? What if my employees are there?” Mindful of bombings in the 90s, he spent the first month learning the layout cold. “I got to the point where I could say, ‘I can’t get lost in here.’” When the attacks happened, Michael was able to quickly and confidently guide his colleagues to the emergency exit.

Battalion Chief Michael Annese echoes the primacy of preparation. “We train for active shooters, hurricanes, fires, stabbings, heli evacs, etc., so when the incident comes you have that muscle memory.” How does this apply to you? Do a quick risk assessment of your daily routine. What are the riskiest places and actions you undertake every day? Where are you likely to encounter an emergency?

Since most of us won’t undertake firefighter-level training, Annese recommends using visualization to project what you would do in an emergency scenario. “Think a couple moves ahead,” he says. “If you’re not anticipating you’re not in a position to be proactive.”

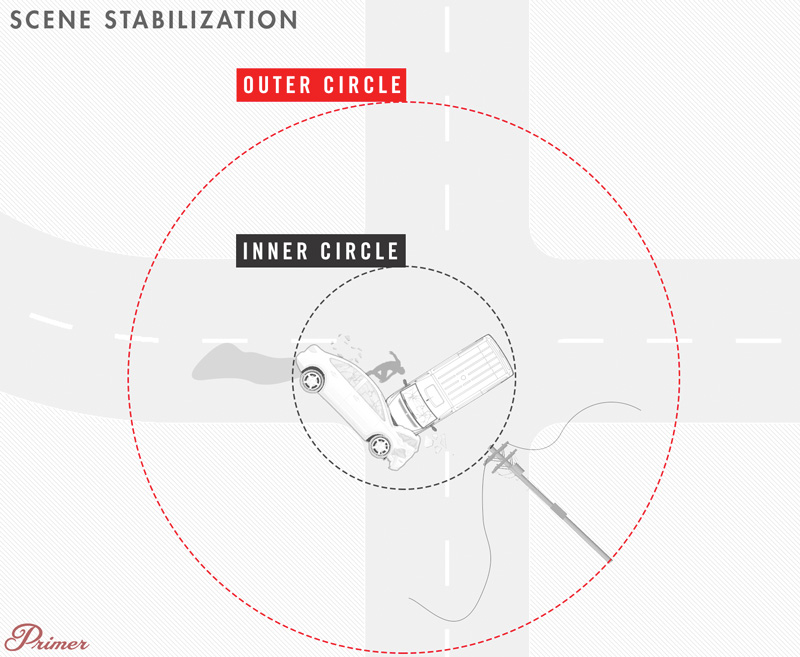

As a quick exercise, visualize coming up to a car accident at a busy intersection near your home. You call 911. With emergency services en route, you’re the only person on site. What’s your first move as you exit your vehicle? “You want to be aware of oncoming traffic,” says Annese, adding, “tunnel vision on the crash site is a common risk.” Next, take note of the hazards. “There’s an inner and outer circle of any crash,” Annese advises. “Look for downed power lines, gasoline, and other dangers at the outer circle.” Then, move to the inner circle and if you’re able, render care.

Embedded in this visualization is something Annese stressed over and over: situational awareness. In Tower 1 on 9/11, Michael Hingson brought a singular situational awareness to events unfolding around him. Shortly after the plane hit, his seeing-eye dog Roselle woke from a nap under his desk. She was calm. “Roselle’s attitude told me whatever was happening wasn’t such an imminent threat that we couldn’t react in an orderly way,” he says. As Michael and his group descended, his blindness was the opposite of a hindrance. Working with Roselle, Michael wasn’t as affected by increasingly smoky and chaotic conditions, which allowed him to project a calm and optimism that was a beacon to others.

This key fact reveals lesson number two: in a leadership situation, use whatever unique assets you bring to the table. Michael’s situational awareness was, in fact, superior to his sighted colleagues due to a lifetime of honing his non-visual senses. He even figured out what had happened based on the smell of burning jet fuel in the emergency stairwell. Where others might see weakness, Michael brought strength. Have you stopped to consider and properly value the assets you bring to an emergency?

Michael’s final action, however, was probably the most important. In dozens of ways large and small, Michael engaged other people. At one point he encountered a woman who said she couldn’t go on, so he gathered people in a group hug and coaxed her onwards. “When it got too quiet on the stairs,” Michael says, “I knew people were starting to go too far into their own thoughts, so I’d say ‘Hey everybody I’m Mike. I’m blind and I have my guide dog here. Don’t worry about the power going out. If it does me and Roselle can offer you a half price special to get out of here today.”

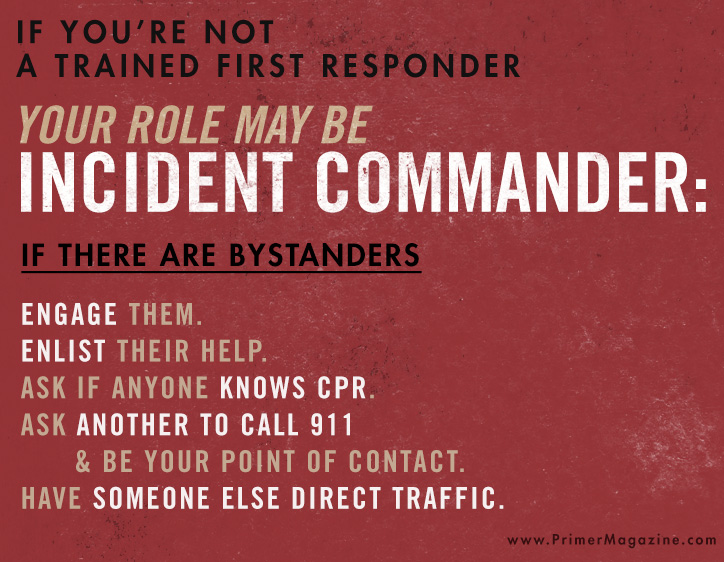

Michael became the de facto manager of the people around him, a crucially important role. “It is important for someone to assume what we call the ‘incident commander’ role,” says psychologist Jerry Smith. “This person directs the actions of others, outlining very specific goals to be accomplished.”

If you’re not a trained first responder, your role may be incident commander. Returning to the car accident scenario, imagine we’ve added some bystanders. Engage them. Enlist their help. Ask if anyone knows CPR. Ask another to call 911 and be your point of contact. Have someone else direct traffic. As Battalion Chief Annese puts it, “If you can get one person to look you in the eye, you can get them to help you out.”

Start with SIN

The takeaways from Michael’s story and the car accident visualization scenario are summed up in a three step process psychologist Jerry Smith recommends for civilians who find themselves in emergency situations: SIN. It stands for 1) Safety First, 2) Isolate and Secure, and 3) Notify. As Smith explains, “The first thing someone should do when coming across any emergency situation is check to make sure it is safe for you (or anyone else) to be there. If it’s safe you can move to step 3. If it is not safe, you will want to make sure no one else enters the unsafe area (step 2).”

The core principle behind SIN is to ensure that anyone attempting to help doesn’t inadvertently become victims themselves. As Battalion Chief Annese explains, “In the movies, they show firemen taking their masks off and giving it to someone else, but that’s a fiction. If you’re helpless you can’t help anyone else.” In summary, SIN means: Secure your own safety. If the scene isn’t safe, isolate and secure it to prevent others from entering. If it is safe, notify authorities and move into render care.

Redefining “Hero”

If you want to extend your crisis leadership preparedness beyond the abstract, go get training in the aspects of emergency response that interest you. CPR, first aid, and Wilderness First Responder are good starting places. Smith recommends, “FEMA has free online training that almost all first responders are required to complete regardless of agency or organization. Anyone can take these online courses.”

It’s also time to redefine what a hero is. For too long, it’s been more Captain America than the neighbor who notices your leaf pile has caught on fire and douses it with his fire extinguisher (preparedness!) before knocking on your door to let you know. A hero isn’t just the person who treats the injured or decks the bad guy. As Smith put it to me, “All it takes is one person to just step up and break the inaction of a group. That person doesn’t actually have to do much – just show the rest of the group that action, any action, is appropriate. Once that happens, the group can save the day.”

![It’s Time to Begin Again: 3 Uncomfortable Frameworks That Will Make Your New Year More Meaningful [Audio Essay + Article]](https://www.primermagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/begin_again_feature.jpg)