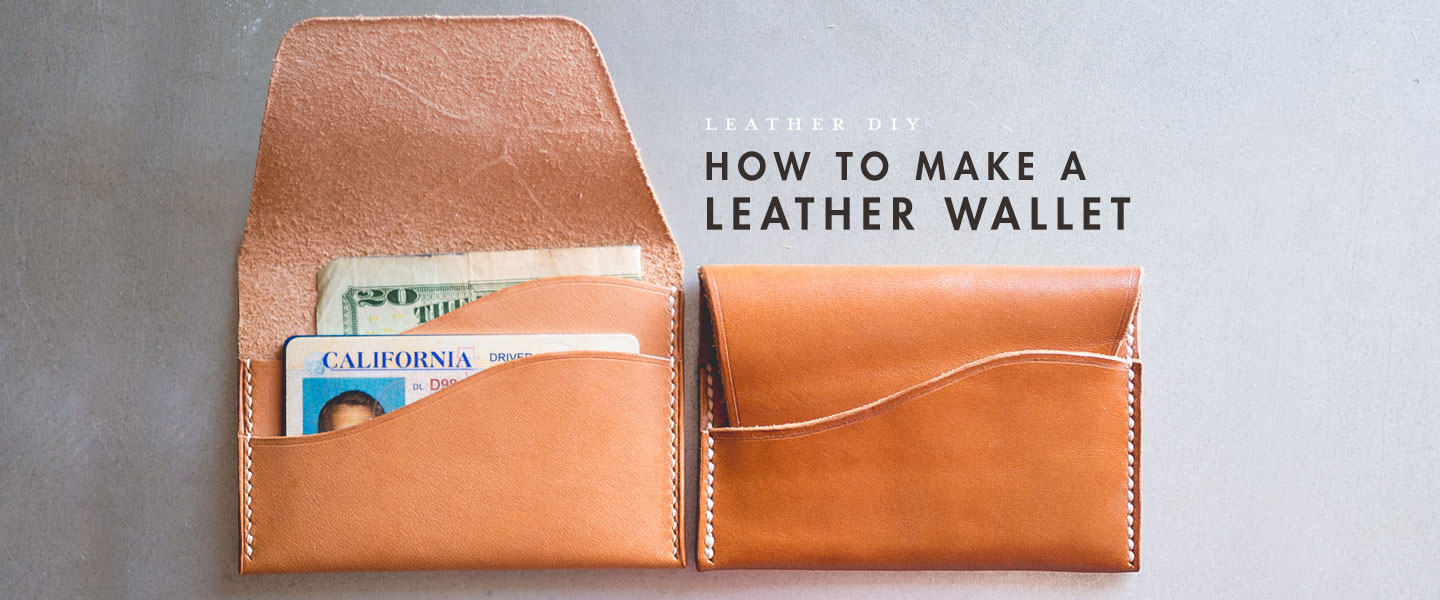

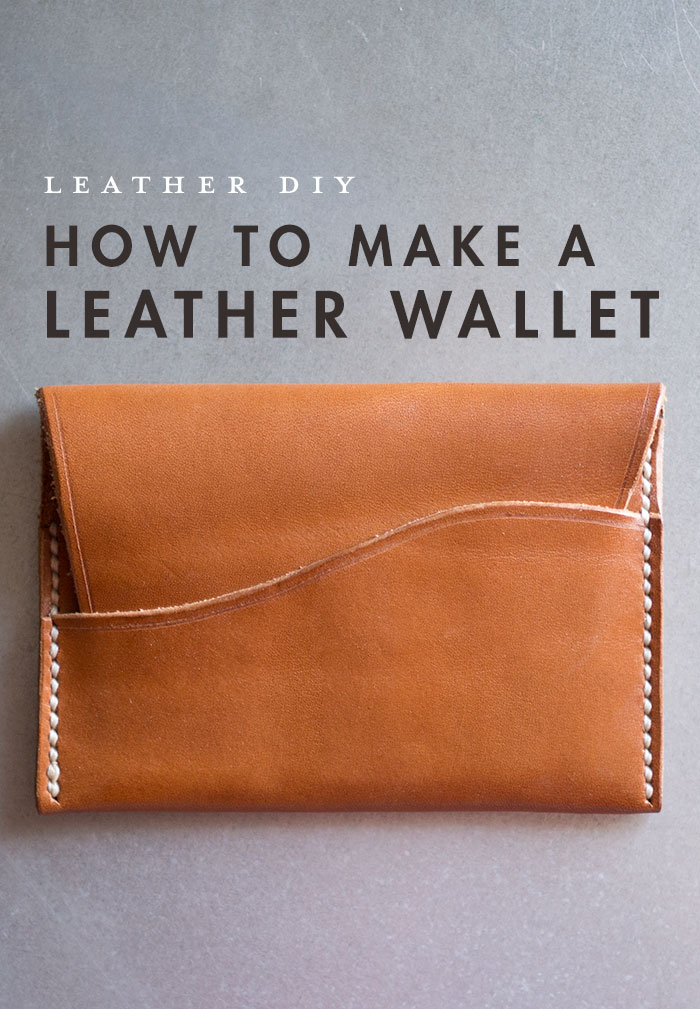

A detailed but easy introduction to leathercraft with a beautifully minimalist wallet project. Watch out Etsy.

By Kevin Lee

Minimal wallets are a classic trend in men’s fashion, and are a good way to lighten up that bulk in your pockets. With some leather and a few basic tools, you can make a very nice one for yourself to use, that will have enough space for a few cards and some folded up cash. With this guide, you’ll learn the basics of leather working that you can also extend to larger projects once you’ve mastered the basics!

For the leather alone, it probably would not take any more than 1 sq. ft. of leather, although more might be needed for mess ups! A great place for beginners to buy single square feet of leather is Springfield Leather. Another alternative is Tandy Leather Factory, which tends to have many brick & mortar stores spread throughout the country. A square foot of vegetable tanned leather should run about $10, and other variants of leather generally will cost similar prices as long as they are not exotic.

Here’s a quick list of the things you’ll need. You can get by with less, but this is what I used in the tutorial and it’s how you’ll get a really nice finished piece. You may have these items already if you made my last leather diy project, a leather watch strap.

- Leather

- 2 needles and thread

- X-acto or sharp knife

- Ruler or t-square

- Stitching chisel

- Leather groover

- Medium grit sandpaper, 200-400

- Contact cement – For gluing the ends of the leather

- Bone folder – For folding the ends of the leather

- Neatsfoot oil – For softening the leather

- Glycerine soap bar – For burnishing the edges of the leather

- Gum tragacanth – For burnishing

- Pure beeswax – Final step in burnishing

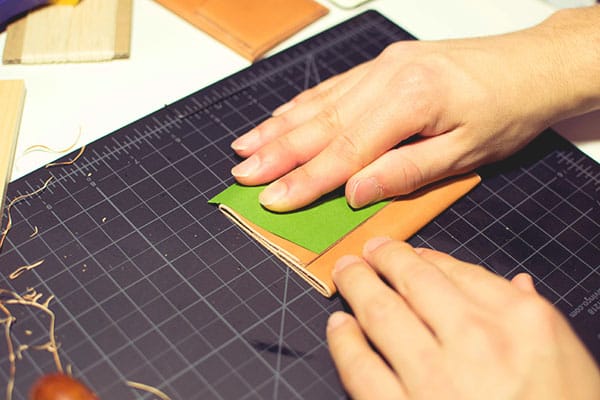

Cutting the leather out is the first step. Unless you have experience sharpening your own knives, a sharp X-Acto Knife works very well for this. The basic dimensions for the body of this particular wallet was 7.5″ x 4.25″

If you have the resources or experience, it's best to use programs like Adobe Illustrator to make a proper template for your project, or make a practice prototype on cardstock or fabric first. Hopefully, in this tutorial you can learn the basic fundamentals of leather working. Enough to get you started on making small leather goods, like wallets, pouches, and the like. There's loads of helpful videos on youtube if you just search what you want to learn, as well as leatherworker.net, a really helpful forum.

Cut the Leather

The curve cut out. I then use this “template” to cut the curves out on the actual pieces I will be using. This ensures a consistent look.

Came out quite cleanly.

Slightly wetting the parts of the leather you wish to bend with water helps out immensely.

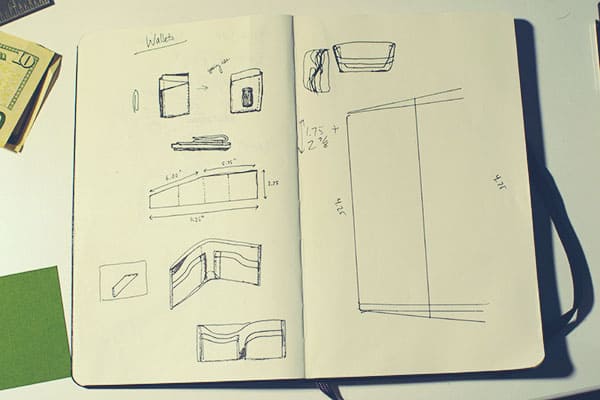

Cutting out the inner pocket piece. (There were 2 total pieces in the wallet) The curve is traced with the same scrap piece.

Testing the fit and look.

An optional, yet helpful step is to condition the leather you're working with. If using vegetable-tanned leather, such as the one I used, the leather can start out quite stiff. After being conditioned with Neatsfoot oil, it can become more pliable and easier to work with.

Trimming the edges of the pieces. If your trimmer is sharp, it should glide easily and make clean cuts without pulling the leather. This step takes off the sharp edges of the pieces and rounds them off.

Laying out the angle for the top flap. I made the right side a little sharper to make it go into the flap easier because of how the “wave” rose up on the right side.

Cutting out the angles with a rotary cutter.

I freehanded the corners around a penny. You don't have to be absolutely exact with corners since you have to trim+sand+burnish them later on anyways.

Burnishing – Sanding

When burnishing your edges, the more steps+time you take results in a better looking edge. The process I use consists of: sanding the edges, wetting the edges with water, rubbing a bar of glycerin thoroughly into all edges, burnishing with a bone folder (the white stick), applying gum tragacanth to all edges, burnishing again, applying beeswax thoroughly into all edges, then burnishing all edges again for several minutes. As you can tell, this is one of the most time consuming processes. My steps are quite excessive, but sometimes using just water and burnishing with that will work well.

How everything looks up to this point.

I use a leather groover to mark a decorative line just below the edges of the pockets.

Closer up.

Burnishing – Water

This is the beginning of the burnishing process. Water is applied to the sanded edge and burnished. If just sticking with water, it's ok to skip the rest of the burnishing steps.

Burnishing – Glycerin

Glycerin is applied.

How it looks immediately after the glycerin. It should already look glossy, but we're far from done.

Burnishing with a bone folder. Thin leathers are usually harder to burnish because if you're not careful you can squish the edges inward, but the glycerin reduces friction greatly, so you can lightly lay it on the edge and just focus on rubbing it briskly.

Burnishing – Gum Tragacanth

Applying gum tragacanth. It's a gummy liquid that gets tacky when dry, which helps the leather fibers stick to each other.

Burnishing – Beeswax

After burnishing the gum tragacanth, applying beeswax to all edges. This is the final step when burnishing. Beeswax helps to further add to the longevity of the leather's edge by waterproofing it.

How the finished edge looks.

Now we're ready to start putting the pieces together. Here, I apply contact cement (Weldwood) to edges that need to be joined. It serves a dual purpose: 1. Hold edges together so that they can be sewed much easier, 2. They hold the very tips of the edges together, which is essential when you're making a burnished edge. If you don't glue them together in some way, your burnished edges WILL fall apart eventually because the stitching cannot hold together the outermost outskirts of the joined pieces of leather. As seen here, it helps to mark the edges of where you will need to glue before actually applying the glue. This way you know exactly where to stop.

Glue applied. You don't need to go too far inwards with it. It's just important that you get all the outer edges thoroughly glued.

You'll need to apply 2-3 light coats of it. Leather is extremely porous and it will practically absorb all of the first layer, and your bond won't be as strong. This was a mistake I made on my first project, and the edges didn't burnish properly because the edges kept coming apart. The glue should look glossy like this on all edges when dry. (Contact cement is ready for use when it's dry and tacky – in about 5-10 minutes)

After joining, it helps to use a mallet to ensure a good bond, since a lot of the cement lies within the fibers.

Last flap cemented and ready for joining.

After all edges are joined, take a very sharp knife (I used my carving knife here) and slowly scrape the edges so that you have a very straight edge. As you can guess, the better job you do of gluing the pieces together, the less you have to do here. If your pieces aren't lined up, they won't look nice when burnished, and you won't even be able to reach some pieces when burnishing.

Here, I use that same tool as before to mark a line for the stitching. Without some sort of indicator like this, your stitching will be all over the place.

Using a stitching chisel to mark spacing accurately. These can be found on places like Amazon for quite cheap. Make sure the chisel is absolutely perpendicular to the leather, or else it might come out at an angle on the backside, which means a bad line of stitching on the backside.

All the holes punched in.

Saddle Stitching

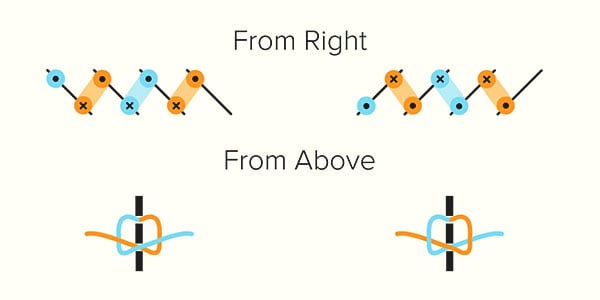

Simple GIF I made of myself stitching. It shows the core process of the saddle stitch. For those who don't know, 2 needles are threaded to opposite sides of a single piece of thread, then they are both run through each hole. This makes the stitching much stronger than that done by machines, because even if the stitching on one side snaps the other side will hold the leather together.

To make your stitching look nice and consistent, it's imperative that the same needle goes over the other one, every time. Here's a nice diagram I found on leatherworker.net back when I had trouble with the concept.

After the last stitch, cut the remaining thread as close to the leather as possible, then use a flame to quickly burn the last frayed thread. Try to poke it back into the hole if it's still sticking out.

Stitching on the back. If your saddle stitching is consistent as mentioned before, the zig zags/slants in the stitching will also be consistent. The thicker ends of the lines are where I doubled back the stitching to lock the remaining thread into place.

As a final step, I apply a liquid mixture of Beeswax + other oils to give the leather some water resistance, but not enough to prevent natural patina over time.

I waited for the cement to set a bit before burnishing the sides, and now I apply beeswax as the final step. I like to really cake it on as shown here. It helps to soften the beeswax by heating it with a flame before rubbing it on.

After it's all been burnished and worked into the leather, here's how the edge should look.

I apply another light coat of Neatsfoot Oil at this point to finish the conditioning.

Finished!

It'll lighten up a bit after the last coat of oil dries.

Close up of the stitching. Neat stitching is important when it comes to leatherwork!

The finished result. Hope you enjoyed reading through!

Be sure to read my other tutorial, how to make a leather watch strap.