You could wallpaper your bathroom with the promises printed on liquor bottles. Words like “authentic,” “heritage,” and “handcrafted” get tossed around like cilantro at a taco bar, but they rarely mean what you think they mean. Some are written in stone by government lawyers. Others were invented during lunch by someone in marketing whose main qualification was owning a pair of Warby Parkers.

Let’s crack the label open.

Bottled-in-Bond

In 1897, the US government took a break from railroads and robber barons to pass the Bottled-in-Bond Act, America’s first real consumer protection law for booze. It guaranteed your whiskey wasn’t secretly made from kerosene, tobacco spit, or the 19th-century version of drywall dust and fentanyl.

Before that, most whiskey came from rectifiers, middlemen who bought raw spirit and “improved” it with neutral grain alcohol, syrups, iodine, or whatever else was handy. Genuine distillers hated it, consumers couldn’t trust a label, and the government wanted a cleaner way to collect taxes. Bonded warehouses gave them all three.

Today, “Bottled-in-Bond” still means:

- One distillery

- One distillation season

- A minimum of 4 years in a bonded warehouse under government lock and key

- Bottled at exactly 100 proof

If your whiskey follows those rules, you’re drinking something even the federal government agrees is legit. Which might be the first and last time that happens.

And far from being a dusty relic, Bottled-in-Bond became a badge of honor during bourbon’s 21st-century comeback, with distilleries proudly stamping it on labels as proof that their bottles were both historic and trustworthy.

Tequila vs 100% Agave

Mexico owns the word “Tequila” the way France owns Champagne: by law, geography, and the power of being deeply unimpressed by shortcuts.

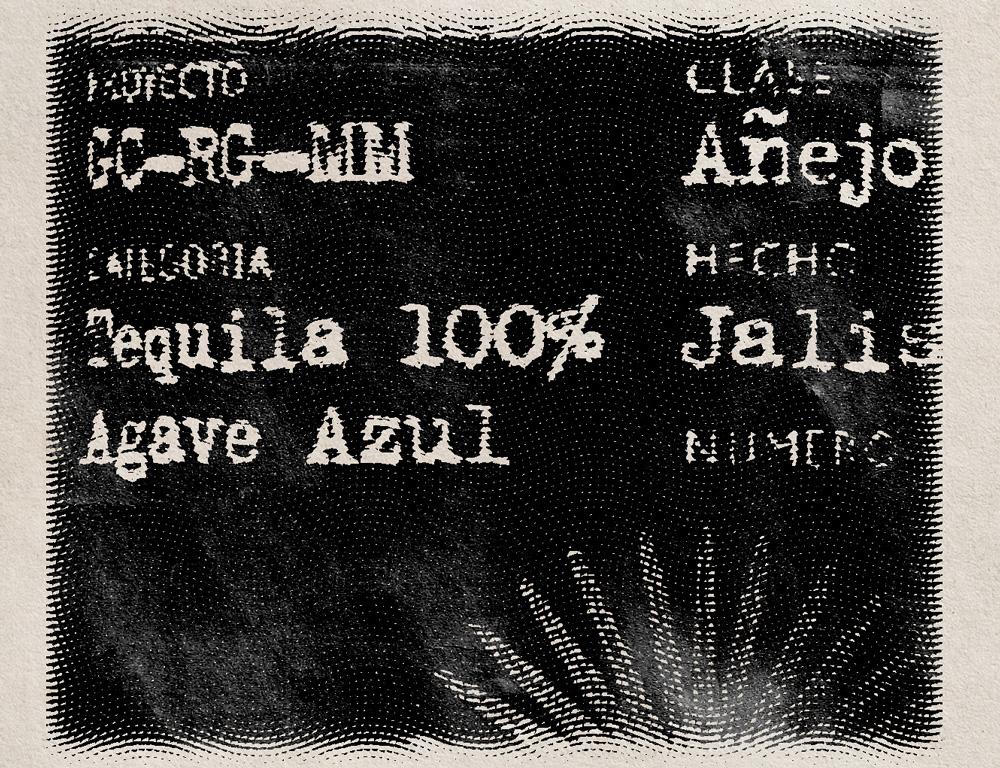

Under NOM-006, real tequila must be made from Blue Weber agave in very specific regions like Jalisco and a few side gigs in neighboring states.

Now, here’s where things get slippery: Tequila only needs to be 51% agave sugars. The rest can be cane sugar, corn syrup, or whatever legally counts as fermentable, which means you’re drinking mixto, not the good stuff.

Bottles that say “100% agave” or “Tequila 100% de agave”? Those are required to be bottled in Mexico and made entirely from agave sugars. But even then, a splash of oak extract or glycerin is still fair game.

And then there’s the NOM code. It’s a government ID that ties a tequila back to its certified producer. Different brands can share the same NOM if they come from the same company or facility, which is less a unique fingerprint and more like realizing your fancy jam and your Lunchables both came off the same corporate truck.

Tequila is one branch of the larger mezcal family. Mezcal stretches wider, with more agave types and traditional methods that often lead to smokier, earthier profiles. It’s not about better or worse; it’s closer to Scotch regions with different rules, different flavors, and different traditions.

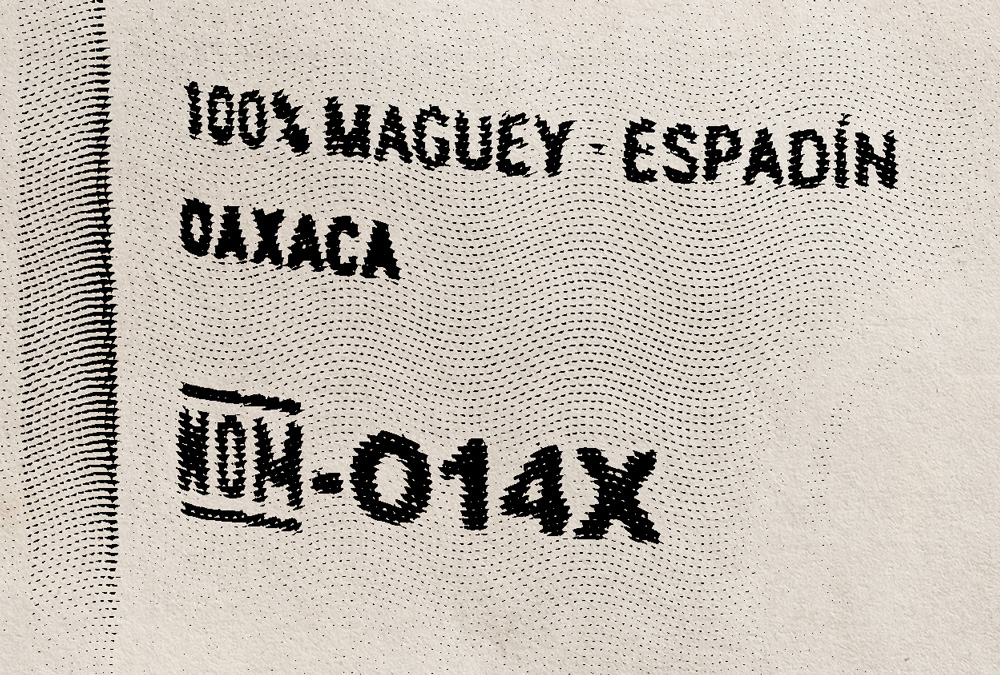

Mezcal runs on the same regulatory backbone but under a different rulebook, NOM-070. Instead of just a number, mezcal NOMs include letters that reveal the state (O for Oaxaca, M for Michoacán, D for Durango), a sequence number for certification, and a final letter tied to that state’s system.

For example, NOM-O191X on Madre Espadín and Madre Ensamble shows both spirits were certified in Oaxaca at the same facility, even if the bottles or agave blends differ. Some labels choose not to display it prominently, or sometimes not at all. The producer might lean on the Denomination of Origin (DO) hologram, QR codes, or other verification marks instead.

So whether you’re drinking tequila or mezcal, the NOM is the same kind of thing: a regulatory ID that tells you where it was certified, not how good it is.

Bourbon vs Straight Bourbon vs Kentucky Straight Bourbon

If bourbon were a person, it’d be the guy in a perfectly ironed Oxford shirt who’s quietly been following the rules since 1964. For something to be legally called bourbon, it has to be at least 51% corn, distilled under 160 proof, barreled in new charred oak at no more than 125 proof, and bottled at a minimum of 40% ABV. No flavors. No coloring. Just legal Protestantism in liquid form. Regulation here.

Straight bourbon takes it further. It must age at least 2 years, and if it’s under 4, the label has to say so. It’s the difference between someone who shows up on time and someone who also brings their own clipboard.

Kentucky Straight Bourbon is where the clipboard guy inherits family land. Kentucky has been the center of bourbon since the late 1700s, when settlers discovered that the region’s limestone-filtered water, corn-friendly soil, and humid summers with cold winters made whiskey practically raise itself in the barrel. By the late 1800s, Kentucky was producing so much that “Kentucky Bourbon” became a shorthand for the good stuff. The state leaned into it, passing its own law that you can’t use “Kentucky” on a label unless the whiskey was distilled and aged there for at least a year. So when you see “Kentucky Straight Bourbon,” it means all the federal straight-bourbon rules, plus the weight of two centuries of local bragging rights.

Proof and ABV

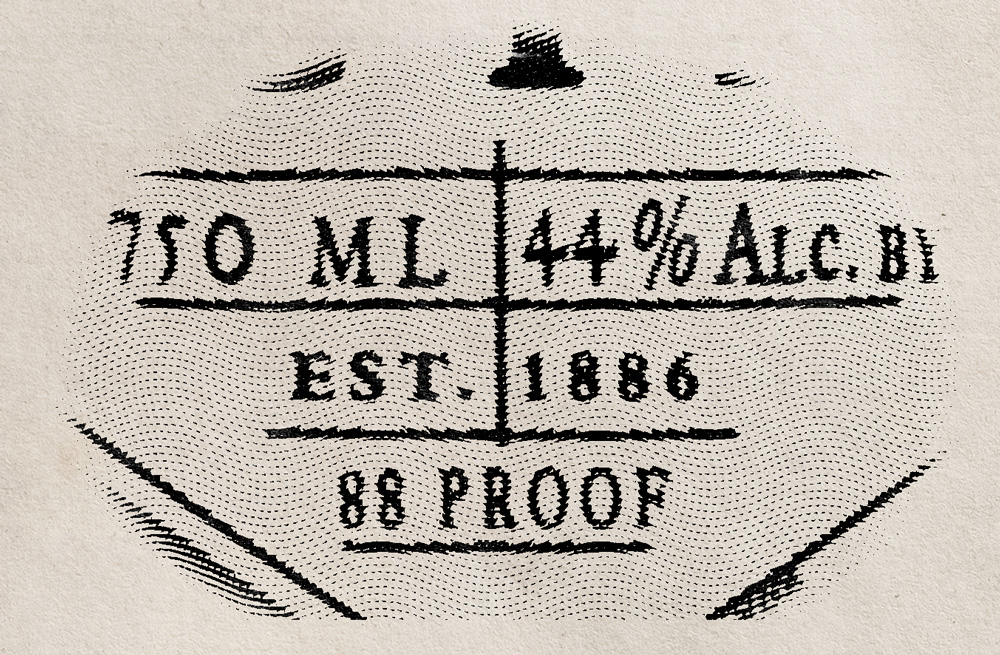

Here’s the trick: in the US, proof = ABV × 2. If you see 90 proof on a bottle, it means it’s 45% alcohol. Nothing mystical. Just arithmetic.

The word proof comes from old English tax law. In the 1500s, inspectors tested spirits by mixing them with gunpowder and striking a flame. If the powder still ignited, the spirit was “above proof” and taxed more. Too weak and it fizzled, too strong and it flared out. The system stuck long enough that by the 18th century Britain fixed 100 proof as 57.15 percent ABV, the point where gunpowder would reliably ignite.

When the US codified its own system in the 1800s, the government cut through the math and made it simple: proof would be exactly double the ABV. So 80 proof is 40 percent alcohol, 100 proof is 50 percent, and nobody needs to light gunpowder on their bar counter to figure it out.

Cask Strength, Barrel Proof, Overproof, & Navy Strength

Barrel proof is the label’s way of saying, “We didn’t water this down.” According to the legal fine print, the bottling proof has to be within two degrees of the original.

Cask strength means the same thing but is technically unregulated.

Most spirits settle at 40% ABV, the legal minimum in the U.S. for calling something whiskey, rum, or gin. Anything stronger than that is considered overproof. It just means “above the standard,” whether that’s a bourbon bottled at 110 proof or a rum that clocks in at 151. Overproof doesn’t have a legal cutoff, it’s more of a warning label that you’re holding firewater.

Navy Strength is the one fixed point. The legend says the British Royal Navy kept rum at 57% ABV so if it spilled on the gunpowder, the powder would still fire. It’s a great story, but it’s mostly marketing lore. By the mid-1700s, the Navy was already using hydrometers to measure strength, and rum and gunpowder were stored in separate compartments of the ship. No one was sloshing rum on cannon charges below deck.

The real “navy strength” number, about 54.5% ABV, came later. When hydrometers replaced the old gunpowder test, officials compared a batch of rums that had historically “passed” the fire test. They averaged the hydrometer readings and locked in 95.5 proof, which translates to 54.5% ABV. That became the official issuing strength, and modern “Navy Strength” labeling keeps the myth alive with a rounder 57% figure. Difford’s Guide explains.

For flavor, overproof spirits hit hotter and carry more concentrated character. Bartenders prize them for cocktails that need backbone, since the extra strength holds up against citrus, sugar, and dilution. Straight, they’re not subtle, they’re intensity in a glass, showing off every edge of the spirit. Personally, I prefer overproof ryes for my old fashioned so I still get that whiskey flavor in balance with the ice and simple syrup.

Small Batch

“Small batch” sounds artisanal. Like someone made it wearing an apron and sells it at the farmers market. But it means nothing legally. Could be ten barrels. Could be two hundred. There are no rules. Just vibes.

Single Barrel

Unlike small batch, single barrel usually means what it says: all the whiskey came from one barrel. No blending. No filtering. Just one moody cask doing its best.

The implication for flavor is huge. With a single barrel, you taste the quirks of one cask’s life, such as where it sat in the rickhouse, how the wood breathed, and how the climate hit it. One barrel might lean rich and oaky, another bright and spicy, another soft and sweet. It’s as close as whiskey gets to a fingerprint.

Single barrel bottles are often positioned as premium not because the rules demand it, but because they let you taste individuality instead of a recipe. It’s whiskey with no safety net, and that’s the appeal for some.

Single Malt

In Scotland, single malt means malted barley, made in pot stills, all from one distillery. It must be aged at least three years in oak. There’s an actual regulation for it.

In the US, we finally caught up. In December 2024, The Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) approved American Single Malt Whisky: 100% malted barley, made at one distillery, stored in oak (new or used), bottled at 40% ABV or more.

Single Grain

Despite the name, single grain doesn’t mean one grain. In Scotland, Ireland, and Japan it means whisky from one distillery, made mostly in column stills, with corn, wheat, or unmalted barley in the mix along with malted barley. All three require at least three years in oak. The style is usually lighter and cleaner than single malt, which is why it rarely takes center stage on its own.

In the US, “grain whiskey” means something else entirely. Federal law defines it as a whiskey made from a mash bill that is at least 51 percent of a specific grain other than corn. Rye whiskey, wheat whiskey, or barley whiskey all count here. American grain whiskey leans on a single dominant grain rather than a multi-grain mix, making it more about one flavor profile than a softer blend of several.

Blended

Once you’ve met single malt and single grain, blending is the next move. Blended Scotch is a mix of those two, all made and aged in Scotland for at least three years.

“Blended” doesn’t automatically mean worse, even if that reputation has followed it for decades. In Scotland, blending single malt with single grain created a whisky that was smoother, more approachable, and, most importantly, consistent. That reliability made blended Scotch the global standard, and it still accounts for almost 90 percent of all Scotch sold.

In the US, the word picked up baggage. American blended whisky can legally contain up to 80 percent neutral grain spirits, essentially vodka, with just enough whiskey for flavor. The result was thinner, cheaper bottles that turned “blended” into shorthand for “budget.” Blended bourbon is stricter, at least 51 percent straight bourbon with the rest made up of other whiskey or neutral spirits. It’s a blend, not a dilution. Usually.

In Canada, blending is the house style. Whisky must age at least three years, and most of it is a mix of grain whisky and flavouring whisky (lower proof but with stronger flavor). Some bottles lean soft and velvety, others land squarely in beige.

So does blended mean worse? Not in Scotland or Japan, where blending is treated as a craft and master blenders are celebrated for creating balance out of dozens of whiskies. In the US, the legal shortcut built its own bad reputation, and the word never fully recovered.

Natural Flavors

According to FDA law, “natural flavors” must be derived from a natural source like fruit, bark, dairy, whatever, but it doesn’t have to taste like that thing. “Natural lime” might contain actual lime oil. “Lime with other natural flavors” could be lemons pretending to be limes.

‘Artificial flavors’ are lab-built, not inherently toxic. The real question is whether it tastes like lemon or like the stuff you mop with.

Real Fruit vs. 100% Juice

If your canned cocktail says “contains real juice,” it could legally mean 1%. The real law comes from 21 CFR §101.30, which says if a product shows or implies juice, it has to disclose how much. Only “100% juice” is guaranteed to be, well, 100%. The rest is just fruit-adjacent optimism.

Non-Chill Filtered

Chill filtration pulls out fatty acids and esters that make whiskey go cloudy in cold glasses. That’s all. If your bottle says non-chill filtered, it might look a little foggy, especially on ice, but that haze contains flavor, body, and a trace amount of smugness. More on that.

Reserve

In the US, “reserve” is completely unregulated. It can mean older barrels, or just that someone liked how the word looked in cursive. In Rioja, Spain, Reserva means red wine aged at least 3 years, with at least 12 months in oak. But that’s Rioja. Your whiskey’s “Grand Reserve Edition” might be aged in nothing more than ambition. Rioja DOCa explanation

Estate Bottled

In wine, estate bottled is real. Under US wine law, it means the grapes were grown, crushed, fermented, aged, and bottled on the same estate, inside the same AVA (American Viticultural Area). This is a federally recognized grape-growing region, mapped out for its particular soil, climate, and geography.

In spirits, “estate” is just a word. Could mean anything. Could mean nothing.

Age Statements

If a bottle says twelve years, every drop inside must be at least twelve. It’s a minimum, not an average. Spirits under four years old must list the age.

![It’s Time to Begin Again: 3 Uncomfortable Frameworks That Will Make Your New Year More Meaningful [Audio Essay + Article]](https://www.primermagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/begin_again_feature.jpg)