“The world breaks everyone and afterward many are strong at the broken places.”

They say that even while seriously wounded, he helped Italian soldiers to safety through a war zone. He once wrote over eighty stories in the space of twenty months just because he felt like it. His beard once grew a beard.

OK, maybe not that last one, but still – he is: the most interesting man in the world’s real-life inspiration.

Ernest Miller Hemingway.

Who He Was

Does this man even need an introduction? Type “man” into a Google image search, and you’ll get a bunch of pictures of guys wishing they were half as impressive as the consummate modernist writer/journalist/adventurer/Nazi-submarine hunter. As a Nobel-prize-winning novelist alone, the man had such an impact on literature that it’s been said every writer since has either had to emulate his style or consciously avoid it. And seriously – he was one of the chief inspirations behind the suave Dos Equis mascot, in spite of his humble origins.

Despite being his swashbuckling career, the start of Hemingway’s life couldn’t have been more dull. Ernest was born to a comfortable, middle class family in a comfortable Midwestern suburb. His parents were respected, well-behaved members of the community who expected their son would follow in their footsteps.

It didn’t happen.

The rest is history.

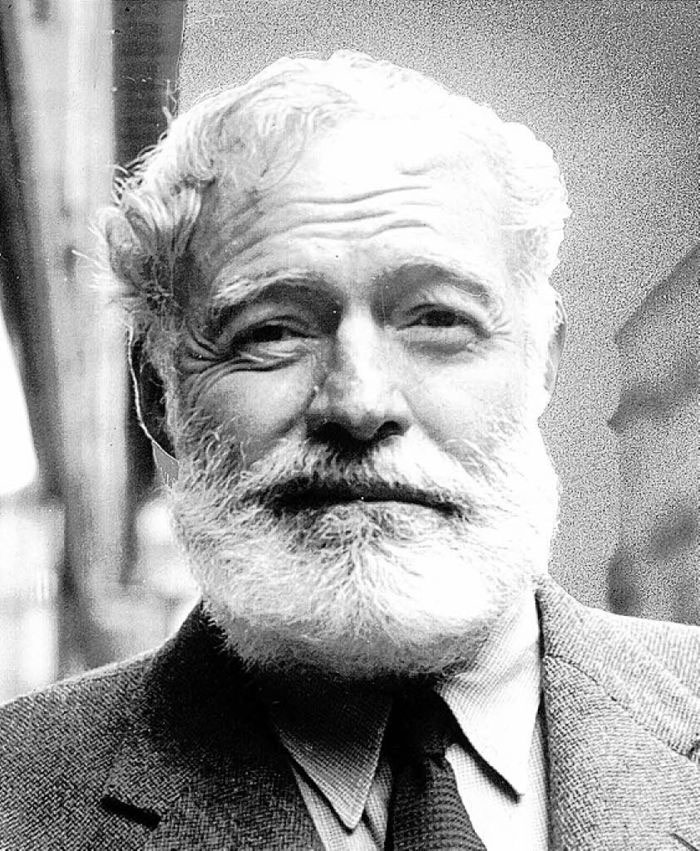

Short stories gave way to novels. Novels gave way to international acclaim and success. Success gave way to more adventures. Hemingway threw himself into chronicling the Spanish Civil War. During WWII, he reported from Normandy, even serving as an advisor to French resistance fighters. When the world ran out of battles for him to charge into, Hemingway came up with his own. He hunted big game in African savannahs. Fished for marlin in Cuba. He became a fearsome boxer. An in intrepid mountaineer. And while he didn’t always drink beer, he could always drink anyone under the table.

Why We Want To Be Him

Where do you even start? With Hemingway, there’s no shortage of attributes to be envied. His legendary status continues to dwarf writers to this day, and for everyone else, his eloquence, courage, and simple toughness make him hard not to admire. Even at the basest level, it would be tough not to want his exhilarating life.

But for most – it’s something deeper than all of that. Something more fundamental. Maybe it isn’t what Hemingway did but the way he did it. Stoically, but with an undying passion for life. Sophisticated as hell, but infuriatingly simple. Sensitive without being weepy. Tough without being callous. At the end of it all, Hemingway wrote the book on what it means to be a man, and according to Hemingway…

A Man Fights

“The worst death for anyone is to lose the center of his being, the thing he really is.”

…And Hemingway knew a thing or two about death.

By the time he was nineteen, Hemingway had seen more destruction and killing than most of us will in our combined lifetimes. And after the brutality and randomness of the front lines of the first world war, Hemingway would watch men and women die in their homes, in hospitals, on mountains, and in the streets. Like so many of what we’d now call the “Lost Generation” – Hemingway struggled to make sense of it all. Brave men died. Cowards died. Sooner or later everyone died, and not a damn thing could prevent that.

So what was the point then?

For him, it was integrity.

What truly distinguished men wasn’t when they died, but how they died – and more importantly, how they lived. Hemingway had watched his own parents stifle the things that made them who they were in order to fit into society. After his father committed suicide in 1928, Hemingway couldn’t but have helped wonder if his old man had died on that cold December day, or if he hadn’t truly been dying every day until then.

What makes a man a man isn’t the car he drives or the house he lives in, but his ability to be true to the fundamental things he believes – the only things a cold and capricious universe can never take away. As Hemingway saw it, a man is only as good as the things he claims to stand for, and those claims aren’t anything more than claims unless they’re put to the test.

Which is why we must all fight. No thought to the odds. No thought to the outcome. Not fighting strictly in the sense of war (which Hemingway often despised), not fighting in the sense of simple violence (though that could be part of it), but the simple act of putting your integrity to the test.

For some men, that meant facing down a charging bull in some dusty arena in Madrid. For others, it meant getting to the top of that mountain no matter how bitterly the winds cut through their coats. For still others, it could be as simple as getting back to the typewriter after a dozen rejection letters from editors, or refusing to move off the picket line, or a dozen other things that prove to the universe that you’re a helluva lot tougher than it is. That you can be destroyed, but not defeated. In his own words:

“A man must comport himself as a man. He must fight always preferably and soundly with the odds in his favor but on necessity against any sort of odds and with no thought of the outcome.”

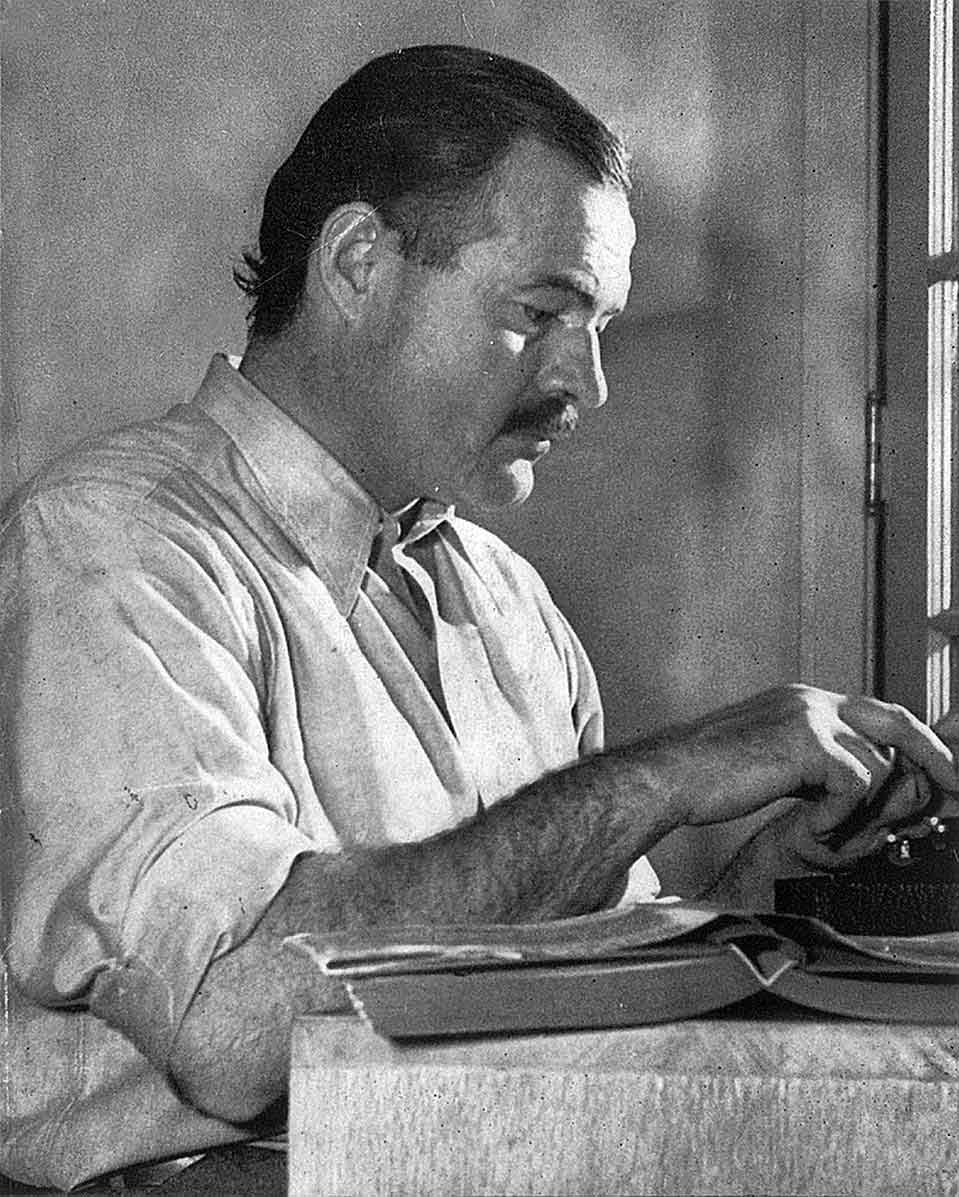

Hemingway posing for a dust jacket photo by Lloyd Arnold for the first edition of “For Whom the Bell Tolls“, at the Sun Valley Lodge, Idaho, late 1939.

A Man Loves

“But it is never a reproach that he has kept a child's heart, a child's honesty and a child's freshness and nobility.”

That’s the second half of the quote from up above, and it’s one that’s too often forgotten.

Hemingway’s swashbuckling life didn’t come without its share of bumps, bruises, and near-fatal plane crashes (two, one the day after the other). Over the course of his adventures, he would battle malaria, pneumonia, hepatitis, a ruptured kidney, spleen, and liver, skin cancer, and broken bones (and those are just the major injuries).

Folks who don’t understand Hemingway too often look at his life and try to model themselves after the worst kind of impassive, cold-blooded 80s action-hero – and they might be forgiven for making that mistake. After all, both Hemingway and his characters alike were absurdly tough bastards who could hammer nails with their knuckles and backhand grizzly bears just for looking at them wrong.

But that’s not who Hemingway was.

Ernest didn’t survive by being apathetic or unfeeling – just the opposite. Like the wise, old master from of every samurai movie ever, Ernest knew that to be able to fight, a man’s got to have something worth fighting for.

Hemingway was a deeply sensitive man. Not an expressive man, not an excitable man, but a sensitive one. Being tough and being apathetic are never the same thing, and Hemingway’s strength came not from being emotionless but from caring so deeply. In a world that’s all too frequently brutish and unfair, the only thing that makes life worth living are the moments of stirring and profound beauty. Not through blind optimism, but a sense of openness to the world, and a willingness to be enchanted and enthralled.

Some of the greatest moments in Hemingway’s writing come not when the protagonist is having his showdown, but in the sections immediately before. In the description of some cool, Spanish morning when our hero’s smelling the breeze through the old pines or feeling the spray of the salt air or watching the sun on the hillside. Its things like these – the little things – that make the world a fine place, and worth fighting for.

A Man Fails (And Keeps On Failing)

Given Hemingway’s incredible life, it’d be easy to assign him some legendary status – to think of him not as a man, but as some sort of adventuring demi-god (he did have a beard that would make Zeus thunder with jealousy). It would be easy to think of him as invulnerable. Invincible. Unstoppable.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

Hemingway failed, and failed constantly. He struggled with fidelity, botching almost all of his marriages. Hemingway lost friends to disputes and fights, often over petty and pointless differences. Hemingway had to contend with the consequences of his heavy drinking, and in spite of his award-winning work, writer’s block became a constant antagonist in his later career. Ultimately, Hemingway would take his own life, following a prolonged and brutal struggle with the same mental illness that lead to his father’s suicide.

Failure happens. A lot.

And it’s OK that it does.

Promotions will fall through. Relationships will end. We’ll let that exercise routine slip. Our team will lose. Sometimes these will be because of some issue on our part. Sometimes it will just be out of our hands. Regardless of the cause, we need to learn to live with it – to not hold ourselves in such high regard that we collapse at the first misstep.

Here we can learn from both Hemingway and his protagonists, who like their creator, were all far from perfect. Many are full of pettiness, self-doubt, anxiety, arrogance, selfish, stubbornness, and all the other flaws that make them (and us) human. That’s not to say these qualities are somehow “noble” – they aren’t. But they are there, and we can’t expect to move forward in life without coming to terms with them. And it’s this that made Hemingway the definitive badass he was. His succeeded not because he thought he was perfect, but because he knew he hasn’t. He didn’t get hung up on every drunken outburst, lousy draft, and failed expedition (of which there were many). He didn’t deny them or ignore them, but when the dust settled, he got back up and started over again. That humility is what kept Hemingway marching along when lesser men would have burnt out or given up.

And it’s what will keep us going too.

Download Primer's Free Art Download of Hemingway to print and hang!

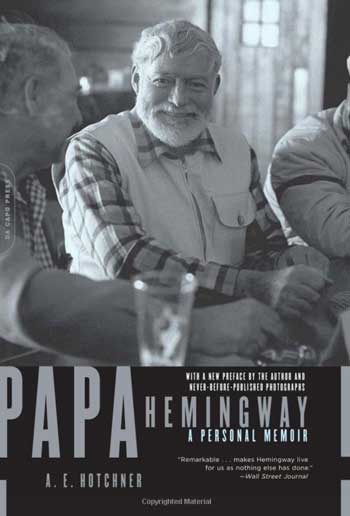

To Learn More About Hemingway:

Hemingway: A Biography – By Jeffry Meyers

Papa Hemingway: A Personal Memoir – By A.E. Hotchner

For Whom The Bell Tolls – By Ernest Hemingway

Read some of his work:

The Complete Short Stores – Free / Amazon