|

This content series is in partnership with smartwater. smartwater, live a life well hydrated. Click here to learn more.

What is this? |

For many of us with big ambitions, there is one thing standing in the way: fear of failure. This fear, however, is by and large irrational. Fear of failure is as irrational as fear of crowds, fear of flying, fear of public restrooms and fear of killer asteroids. Fear of failure is equally as crippling as these fears as well. But contrary to the aforementioned fears, the fear of failure isn’t irrational because failure is as unlikely as a plane crash, a real-life Armageddon by asteroid or getting an STD from a toilet seat. Actually, part of the reason that you shouldn’t be afraid of failure is that it’s inevitable. The other part: failure is beneficial. In fact, if you haven’t seen success in your life, it’s probably because you haven’t failed enough.

Failure is one of the key ingredients to success. Failing at something that you truly want to achieve is actually the second most productive thing you can be doing (the least productive thing you can be doing is nothing). This is true for almost everyone. If you ever see someone brazenly waving the flag of success, I guarantee you that they are doing so from atop a mountain of past failures. They didn’t succeed in spite of those failures—they succeeded because of failure.

Let me explain.

Failure is Exploration

For goals big and small, a misconceived or misperceived lay of the land can be one of the biggest pitfalls. Before we’ve given something the old college try, we have a tendency to underestimate the distance and obstacles between point A and point B.

Let me give you a quick personal example.

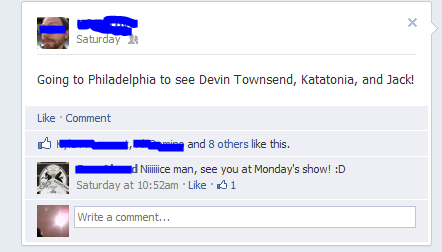

Recently, I got back in touch with one of my old high school buddies. We had always been good friends, even roommates and bandmates for a time, but after college, he moved to Utah and I moved to Pennsylvania. As such, we hadn’t had face time in nearly a decade. But good news! He was going to a concert in my new hometown. We made plans to meet up after the show. I got some vague details about the venue and started making up the guest room. Around midnight, I started wondering about his whereabouts. So, I thought I’d check Facebook and I saw this post from earlier that day:

“Going to Philadelphia to see Devin Townsend, Katatonia, and Jack!” it said. That was all well and good. Except for one thing: I live in Pittsburgh.

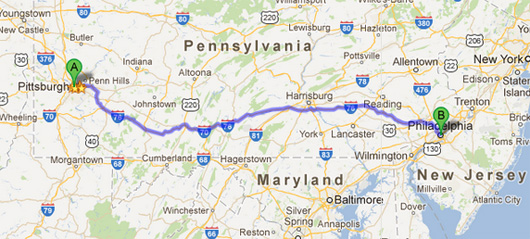

For those of you unfamiliar with Pennsylvania, may I present to you a visual aid:

True, Philadephia is much closer to PIttsburgh than Utah. But he was still not in a very strategic location for crashing at my place for the night and then heading back to D.C. (where he now lives).

To my friend’s credit, I was never very specific about where in Pennsylvania I lived. We both made some pretty bad assumptions and we never ended up hanging out that weekend. Next time, though, we’ll probably wind up in the same zip code.

That’s a very literal example, but it applies to other goals and destinations as well. Until we actually try to get there, we often have no idea how far away “there” actually is. And because of that, we risk under-preparing for the journey.

Let’s say you have the big goal: start a restaurant. You spend most of your days thinking of all the fun things: the menu, the decorating, the clever marketing ploys. You even start mapping out the obvious milestones: perfecting a signature dish, finding a location, hiring chefs and managers. You think about these things night and day, you trawl forums and even pick the brains of a few seasoned restaurateurs. But as soon as you take the leap, you find out that there are a million things that you hadn’t considered yet. What kinds of permits do you need? How are you going to get a liquor license? How will your business entity be structured? Where will you buy your produce? How will you get a loan? How do you make a business plan?

Even if you do all your homework, there will be certain blind spots that you encounter cold. These are often the areas where you will fumble and possibly fail. But the good news is that next time around, you’ll know what to expect and you’ll have a plan.

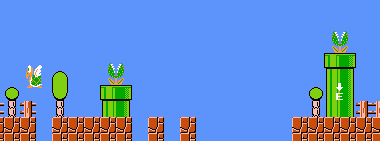

Think of it like World 8 on Super Mario Bros. The first time you hit that huge pit with the piranha plant on both sides, you’ll probably fall right down the drain. You’ll probably die 50 times bumping into the other baddies on the map. But with each guy, you’ll get a little bit farther and a little bit wiser about each hazard along the way.

In the same way, exploration through failure is the key to nabbing the top of the flagpole and hearing those fireworks. You’ll have to sacrifice a few extra lives to uncover the map, but once you’ve shed light on those uncharted territories, the way forward will be clearer.

Failure is Experimentation

Thomas Edison is quoted as saying: “I have not failed. I’ve just found 10,000 ways that won’t work.” Whether he ever said that on the record or not, the sentiment is the core of experimentation. As Merriam-Webster defines it, an experiment is:

“an operation or procedure carried out under controlled conditions in order to discover an unknown effect or law, to test or establish a hypothesis, or to illustrate a known law”

Other definitions specifically mention that an experiment is a methodical trial and error procedure. The keyword here being “error.” Trial and error is best applied to methodical problem solving. In fact, for many disciplines, such as mathematics, programming and medicine, trial and error is the main method of problem solving. If you believe in evolution, then your very existence as a human being is the product of billions of trials and errors.

Like the exploration facet of failure, experimentation helps you learn more about the problem. But each trial and error also helps you learn more about the tools and assumptions you are bringing to the table. Each time you throw something new at the problem, it reveals a little bit about the nature of the problem and the nature of your methodology. It tells you what is working and what is not. But it can also reveal peripheral knowledge about your tactics that, while not immediately useful, may be handy for another problem.

Take WD-40, for example. WD-40 stands for “Water Displacement, 40th formula.” In order to settle on the formulation for this now household name, the inventor Norm Larsen had to go through 39 “failed” formulations. Although the development of WD-40 was undoubtedly methodical, it’s unlikely that WD-2 was obviously better than WD-1, WD-3 was an incremental improvement on WD-2, WD-4 was the best thing since WD-3, etc. But the totality of all this experimentation—the 39 “failures” as a whole—are what made WD-40 possible.

And here’s the kicker: WD-40 wasn’t originally designed for unsticking rusty screws, silencing squeaky hinges or any of the other scores of household uses that WD-40 is famous for. It was developed for a very specific purpose: to protect the outer skin on the Atlas missile from corrosion. What the makers of WD-40 learned about coating rockets ended up being an even bigger success on the consumer market.

So, the next time you try and fail, don’t think of it as a waste of time. Think of it as another data point that contributes to the perfect formulation of success.

Failure is an Equalizer (of Odds)

So, what if you’ve overcome your fear of failure. You’ve put in your hours, done your homework, learned all the lessons and you still fail. Even failures like these, where you’ve done absolutely all the right things, are good. Look at it this way:

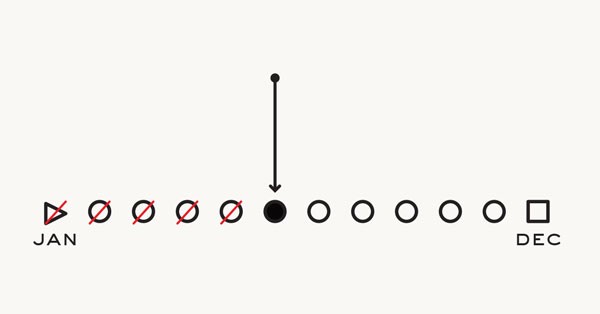

Let’s say you are competing for a job. It’s down to you and five other guys. Let’s say that, through some magic of the universe, all five of you are equally matched in every way. You have the same experience, skills, level of education, dashing good looks, etc. Based on that, which one of you gets chosen is nothing but a matter of chance. There can only be one winner, and so the hiring manager is going to have to make some sort of arbitrary decision, since no one is differentiated in an objective way. The hiring manager chooses, it’s not you, and you fail.

What happened here is that, given the circumstances, the only thing standing between you and success was probability. You had a 1 in 5 chance of winning that position. If there is truly nothing left for you to improve upon, examine or evaluate, then there is only one way to turn that situation into a success: fail four more times. If there is a 4 in 5 chance of failure, then the way forward is simple. Fail all four times and then on the fifth, you will be successful (assuming you didn’t beat the odds before that).

Of course, it’s not always that clean cut. You won’t ever be in a situation where things are truly evenly matched among you and your competitors. The odds won’t ever be as simple as 1 in 5, or 1 in 100 or 1 in a million. But no matter what the odds are, they will be increasingly more in your favor at each attempt. If you have to hear “no” 100 times before you hear a “yes,” then all you have to do to get 10 answers of “yes” is to hear “no” 1,000 times.

This is the principle behind mass marketing. And if it works for those telemarketing scumbags and spammers, it can work for you. This is especially true because you won’t be spraying and praying. You’ll be applying all the things you’ve learned from your past failures and making your next attempt better than your last.

Need more convincing?

Consider the following:

In 1899, a young entrepreneur took a big risk by leaving his illustrious career as an engineer at Edison Illuminating Company and founding a company called Detroit Automobile Company. A brilliant mind backed by three politicians, the venture seemed very promising. But the engineer proved to be a bit too fastidious with the designs, and the company only produced 20 vehicles before it folded in 1901, just two years later. The company reorganized under a different name, but again failed to meet the founder’s vision. He left the company, and without him, it flourished into one of the most recognized names in automobile history: the Cadillac Automobile Company.

But what became of our down and out hero? He started yet another company, this time partnering with a Detroit-area coal magnate and entering into a strategic $160,000 with a local machine shop. In spite of a an innovative design, sales for the company remained slow. And when the machine shop started demanding payment for the first delivery, there was a crisis of liquidity. Rather than folding, the engineer’s partner landed another group of investors and convinced the machine shop to buy into the reorganized company: Ford Motor Company. The rest is history.

By no means were Henry Ford’s previous attempts complete and abject failures. But it’s worth bearing in mind that the automobile that changed the world was the Model T, not its predecessors the Model A, the Model K or the Model S. It’s also worth noting that Ford’s early efforts weren’t the only failures in the company’s history (Ford Pinto, anyone?). The fact that Ford’s eventual successes outweighed its inevitable failures is what helped this American business withstand The Great Depression, the rise of foreign automakers and the 2008 financial crisis.

More examples:

If you visit the House of Happy Walls, you’ll find a room where approximately 600 rejection letters plaster the walls. The writer they were rejecting: Jack London, who wrote White Fang, Call of the Wild and Martin Eden (the third of which is a semi-autobiographical work that starkly illustrates failure coming before success).

One athlete is quoted: “I have missed more than 9,000 shots in my career. I have lost almost 300 games. 26 times I’ve been trusted to the game winning shot, and missed. I have failed over and over and over again in my life. And that is why I succeed.” You might know of him. His name is Michael Jordan. [Relevant Nike ad]

Theodor S. Geisel’s first children’s book was rejected so many times that he considered burning the manuscript. By his count, the book received 26 rejections before it was picked up by Vanguard Press. The title: And to Think I Saw It on Mulberry Street by Dr. Seuss.

As a comedian, he was booed off the stage during his first appearance at a comedy club. As a sitcom actor, he played the bit role of Frankie the courier on Benson but was fired after three episodes. Today, Jerry Seinfeld is quite famous as both a stand up comedian and a sitcom actor.

Conclusion

That all being said, I understand why you fear failure. I fear it, too. But what you and I both fear isn’t the impact of failure. It’s the feeling of failure. The feeling of failure is, well, shitty. It sucks to lose. It’s embarrassing, it’s awkward and it’s inconvenient. But it shouldn’t be discouraging.

This is because failure is never ever a waste of time. The only time you truly fail is when you give up. If you face failure 1,000 times but succeed on the 1,001st try, then all those previous attempts are now longer failures: they are training.

If you find that fear of failure stops you from putting forth your best effort (or any effort at all), I implore you to stop. Stop being afraid of failure and embrace it. Because in the end, failure today is the only thing that will allow you to succeed in the future.