|

This post is made possible by Indochino. Your next suit should be crafted to your exact measurements. Design yours at indochino.com.

What is this? |

Out of all seasons, winter truly tests a man. It tests his grit, his driving capabilities, his mental fortitude (commuting to work before the sun is up and coming home when it’s down can really do a number on you.), and of course, his ability to stay warm.

But it’s also the best damn season for suiting in the year.

In what other season can you find yourself in a luxuriously warm cashmere scarf and overcoat drinking a steaming cup of coffee and breathing in air so cold and crisp it feels like you’re inhaling the summit of Everest? No other season. That’s why winter is the best.

Although you might think of winter suiting as drab and boxy, nothing could be further from the truth. A winter wardrobe well-assembled is as sharp as anything. You just have to make sure you know what you’re doing.

Fabrics: Weights and Types

As for the types of fabric, there are two that reign supreme: Wool and flannel. These two fabrics keep you insulated. That’s why you’re not going to be wearing wool of more weight (more on that in a second) in the summer. The opposite applies as well. Linen, cotton, and thin blend suits are reserved for sipping mint juleps at the Kentucky Derby in the summer heat — not keeping you warm in thick, wet snow.

A flannel suit

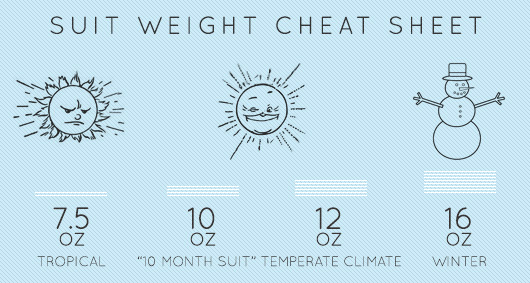

If you find yourself shivering in a suit during the winter, it’s most likely because the weight of the fabric from which it’s made is too low. Yes, there are different weights of fabrics. And they do matter.

When looking into suits that actually keep you warm, look into one around the 16-ounce range for both flannels and wool. They’re thick enough to keep you warm, but they’re not so heavy they look like you’re wearing a cropped overcoat.

Think of this number as the heftiness of the wool itself. The number you see (in ounces) comes from how much a yard of a given wool cloth weighs.

Thicker wool and flannel in the winter. If you get anything out of reading this article, it should be that.

And that’s for a reason.

Both flannel and wool have great heat-keeping abilities and stand up to the actual structure of a suit. Both have pros and cons—GQ recommends keeping flannel away from trouser bars on hangers unless having a big mark on them is your thing and wool can come in a dizzying amount of different varieties.

It’s a pretty simple thing to note: The higher the weight (ounces), the heavier the fabric, and for worsted wool (combed and spun wool), the higher the number of twists, the smoother the garment will be.

What is a Worsted Suit?

You’ll hear the term worsted come up quite a bit in reference to men’s wool suits. Most wools are created from spun yarns; with worsted wool, the wool fibers are first carded (detangled and straightened) to remove short and brittle fibers. What remains are the long thin strands, which are then twisted and spun into yarn. The longer strands create a finer and more durable wool.

What are Super 100s, Super 120s, and So On?

There’s also the designation of “super.” You’ve likely heard the term “Super 100s,” “Super 120s,” among others. This is a measure of the quality of the raw wool before it’s even made into a suit. Another history lesson: The number is derived, historically, from how many 560-yard-long spools (called hanks) a pound of the wool could yield. A grading designation was established: “70s” if a pound could yield 70 hanks, “100s” if a pound could yield 100 hanks, etc. Contrary to popular internet lore, the number is not an indication of how many twists a yarn has. “Super” is a superficial classification added to any number over 100, started as a marketing ploy in the early 1960s by the most prominent spinners in Yorkshire, Joseph Lumb & Sons.

Technology’s advanced a little while since the 1700s, when the initial classification began. A super number nowadays basically refers to the fineness of the actual strands of wool. The higher the number, the finer the fibers. The finer the fibers, the more you get in a pound. Generally speaking, the higher the number, the more expensive the suit will be.

A suit with a high super number means the actual fabric is softer and smoother and silkier (and more resistant to wrinkling). Buyers beware, though: This number isn’t heavily regulated, and it’s nearly impossible to confirm the S-number on your suit is actually what you got. The Wall Street Journal did a test on 10 suits ranging from $290 to $1,995 and found 4 had a lower “super” number than advertised.

Super 100s and 150s are basically a nice fine line. Textiles within that range will be strong, soft, and supple—and won’t cost you more than a down payment on a car.

Tweed: The Rugged Gentleman’s Fabric

Tweed, which is a form of woolen fabric in contrast to a worsted, is a great choice for those looking to give your wardrobe a traditional twist. Unlike worsted wool, tweed is known for its rough texture.

The nice thing about this texture is that it adds visual interest as opposed to the sleek look of a worsted wool. That’s not to say that all tweed fabrics feel like stitched-up burlap sacks, either. Rougher? Yes. But really, the best description of tweed is “rugged.” It was made for hardworking Scotsmen in places that look like the last hour of Skyfall: Misty, dark and cold.

It’s also been around for about 300 years. Starting in the 1700s, weavers in Scotland spun virgin wool (wool that isn’t salvaged from other fabrics—so basically wool that’s being used specifically for the garment) to create a truly durable cloth that, when made into a garment, kept its wearer warm and protected.

Legend has it that a London merchant misread a correspondence about “tweels” (the then Scottish word for “twill”) as “tweed” (as the fabric was made in the Tweed Valley) and the name was coined.

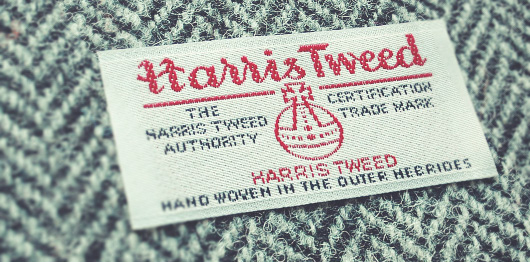

When researching some tweed garments, you’ll undoubtedly run into “Harris Tweed.” This handwoven fabric (which is actually protected and easily recognized by “the Orb”—a trademark logo of authenticity) is made by the residents of the Outer Hebrides of Scotland and is rich in history. And, of course, because it’s handmade, rich in quality as well. Hell, it became famous because it was so beloved by Lady Dunmore, a personal assistant to the queen. But that doesn't mean it's prohibitively expensive: Since it's been around for so long, you can easily find Harris Tweed sportcoats at thrift stores.

Similar to Harris Tweed is donegal tweed. Made in County Donegal, Ireland for hundreds of years, the area is best known for a particular tweed sewn with small pieces of colored yarn in irregular intervals to produce a heathered effect.

The bottom line is that tweed is a fabric that’s been keeping its wearers warm and dry for centuries. That hasn’t changed.

Patterns

Barron Cuadro, founding editor of Effortless Gent, knows classic, and forever-stylish clothes. And now that the Intro to Wool 101 class is over, let’s get back to business.

You’re likely to see herringbone and houndstooth during the winter season, but Cuadro has some more specific tips to bring it all together.

“Plaids are always a popular choice,” he says. “They look great with tweeds and flannels, and other suits with a more subtle, monochrome pattern. Pattern complementing patterns by playing with scale and contrast.”

The Fit

Just like in any other season, the fit of your suit is key to not looking like a poorly maintained mannequin. It’s easy to remember the warmth of a big down coat, but you don’t have to sacrifice the integrity of your silhouette for warmth. It’s just different: A well-fitting winter suit isn’t necessarily the same as a well-fitting summer suit. Why? Glad you asked.

Staying Warm is About Layering

We all know this, but it might be difficult to let your brain transfer that knowledge into suiting. If, for instance, you’re just accustomed to wearing the same undershirts with the same shirts in the same suits with the same ties, it can be tough to ease yourself into a new routine come winter.

Cuadro backs layering for warmth with the general rule of keeping thin layers against the skin with thicker layers as they get farther from your body.

“[And] never underestimate the usefulness of a thin quilted vest,” he writes. “Great under an overcoat or sportcoat.”

For those who spend a lot of time outdoors in the winter, apply the same principles to your winter suiting wardrobe. Wear a base layer instead of an undershirt, wear a thicker shirt over it and a winter-weight jacket over that. Hell, you can probably start sweating just thinking about it.

Additions

This is really the best part, isn’t it? All the things that winter “forces” us to wear that make cold-weather suiting so exact, severe and elegant.

For the things that touch skin, Cuadro has one overarching piece of advice: Stay in one weight class. What this translates into is foregoing your favorite silk tie if you’re wearing a tweed suit and instead knot on something more appropriate (or whatever the non-HGTV word for “festive” is).

Believe it or not, a wool or woven tie actually can help keep you warm—just note that the knot is going to be bigger.

For a thicker tie, you'll need a better knot. Check out “How to Tie a Kelvin Knot.”

Lastly, don’t leave your shoes’ welfare to luck. Really. Salt ruins leather like nothing else short of intentionally trying to wreck your footwear if you’re not extremely careful.

“Bean boots are lifesavers!” Cuadro writes. “If possible, wear Bean boots and bring nice shoes with you to work, and change (or leave extra pairs in your office).”

And for those who don’t want to carry boots or extra shoes with them can get galoshes. Yes, galoshes. They might not be something you’ve thought about since reading about them in Catcher in the Rye, but Cuadro recommends them—Swims, particularly— and a quick search reveals that there are some pretty sharp looking galoshes nowadays.

If you’re looking to get a cap, be sure you’re taking note of how tight it is on your head. One of those gas station beanies will basically force your hair against your scalp, while a thicker, looser wool hat will keep your head warm and your ’do in order.

That’s really the fun of winter suiting: additions.

So instead of dreading the colder months, take these words and go with confidence. Find a heavyweight suit that’s smooth and silky (or maybe even a Harris Tweed jacket) and layer purposefully and you’ll be warmer than you thought possible.

No matter how snowy the evening, how deep and dark the woods, and matter how many miles you have to go before you sleep, be comfortable in your suit.

And look good damn good doing it.