So you had it all figured out.

You were going to get to work early and print out your handouts for the big meeting this afternoon, only to arrive and find the printer isn’t working. You were about to get your dad a nice pair of gloves for his birthday when you learned that your mom already got a set for him. Your weekend basketball team is on the precipice of victory when your power forward somehow manages to sprain both ankles at once.

Life happens.

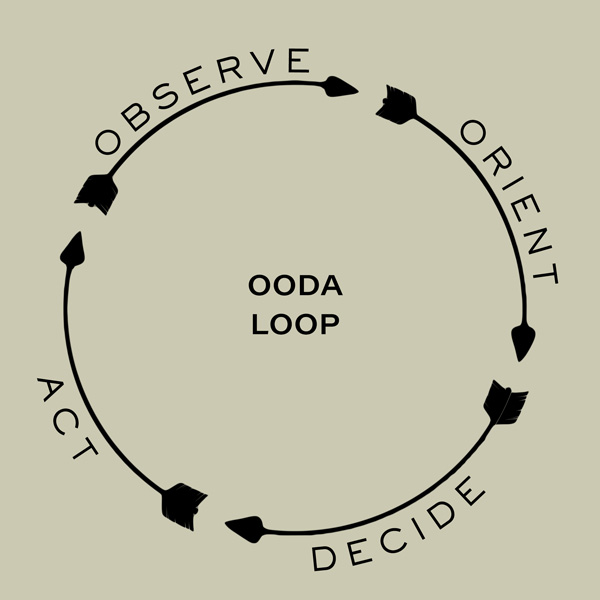

When our best-laid plans get completely upended by the utterly unexpected, how do we get ourselves back on track? The secret lies in a commonly-used but little-known process designed to help anyone overcome chaos: the OODA Loop.

The History of the OODA Loop

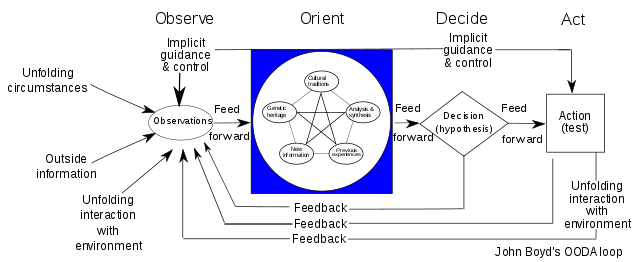

Developed by Air Force colonel and tactician John Boyd in the early 1960s, “OODA Loop”, which stands for “Observe-Orient-Decide-Act”, was originally created as a way to help fighter pilots gain the upper hand in combat. At a time when Cold War tensions and breakthroughs in technology meant that air combat was more crucial and complex than ever before, life, death, and global armageddon all hinged on split-second decisions made 50,000 feet in the air.

Despite having initially been built for high-stakes dogfights, Boyd’s OODA Loop system (like its counterpart, the Eisenhower Matrix) managed to be both so effective and incredibly simple that it’s since been applied to nearly everything in modern life – from business to sports to politics and more.

While you’ll most frequently hear about the OODA Loop system in the context of competition, the process still has plenty of applicability to our own lives. The hurdles we face on a daily basis might not be explicitly adversarial (and hopefully won’t involve the possibility of nuclear armageddon) but just because we’re not up against an ace pilot or an enemy corporation doesn’t mean we’re not up against something.

More often than not, the randomness of the universe is more than enough to keep us on our toes, and it’s at times like these that the OODA Loop can train us to think both more quickly and creatively in situations that would throw others completely off balance.

Why Humans Need the OODA Loop

Boyd references three principles to emphasize how difficult it can be for people to adapt to quick changes in their environment or experiences: Gödel's Incompleteness Theorems, Heisenberg's Uncertainty Principle, and the 2nd Law of Thermodynamics.

- Gödel's Incompleteness Theorems claim that our understanding of the world can never be complete.

- Heisenberg's Uncertainty Principle states that there's always an element of uncertainty in our observations and understanding of the world.

- The 2nd law of thermodynamics states that randomness or disorder rises in closed systems. Boyd applies this more broadly to other areas of life. In the context of the OODA loop, this means that a fighter pilot must continuously draw in information from the environment to avoid becoming chaotic and disorganized. They should also try to isolate their adversary and force them into a closed system.

Boyd believed that by using the OODA Loop to continuously observe, orient, decide, and act in response to changing circumstances, we can adapt and overcome uncertainty and ambiguity quickly.

The OODA Loop starts with…

Observe

Make a habit of reviewing your current status. Are things actually as they appear?

Prior to detailed radar on fighter planes, constant scanning of the sky was a pilot’s greatest tactical advantage over an opponent. It might be easy to dismiss step 1 as obvious, but the harsh truth is that most of us aren’t especially great at maintaining awareness of our current situation. For those of us who are natural planners (and let’s face it, if you’re a Primer reader, you’ll probably fall into this category), it can be easy to focus so much on our ultimate goal (whether that’s the success of the office holiday party or where we want to be in five years) that we lose sight of the current circumstances we’re actually in.

For the pilots that Boyd trained, “Observe” meant not just thinking about their ultimate objective but teaching themselves to stay focused on their surroundings and instruments at the same time. For us, it means making a habit out of intentionally assessing our current situation.

Again, it may sound obvious, but how many times have we run into headaches (and full-on fiascos) by failing to catch changes as they were happening?

If that constant checking sounds tedious, make no mistake – it absolutely is. The good news? It will get easier.

When we were learning to drive, we had to remind ourselves to check our mirrors before changing lanes – something that, with practice, has become instinctual. The exact same is true of the OODA loop, whether that means maintaining awareness of our immediate situation or even applying that principle on a big-picture scale by training ourselves to stay on top of our finances or in touch with our emotions.

Getting that information is crucial but it’s just the starting point. Next, we have to…

Orient

Don’t hope the situation fits your plans. Make your plans fit the situation.

A huge part of being effective in the moment is by responding to the situation we’re in, not the situation we wish we were in. That might sound like an empty statement but there’s a surprising amount of depth behind this step of the OODA Loop.

When we discover something unexpected popping up on our metaphorical radar, the natural reaction a lot of us are going to have is to simply reject it. Thanks to the squishy lie-factories in our skulls, when our plans get disrupted, we’re still going to find ourselves wanting to stick to those plans even in the face of new and changed circumstances.

We have to let go.

As much as our cognitive biases scream at us to stick to the course, being able to survive and thrive in constantly shifting situations means being able to intelligently shift our strategy or plans along with them.

To orient oneself in a rapidly changing environment, it's necessary to break apart old paradigms and put the resulting pieces back together to create a new perspective that better matches the current reality. This approach, beginning with “destructive deduction” and followed by “creative induction,” involves continually repeating the process as mental models quickly become outdated in a changing environment. It is a way to adapt and update one's understanding of the world in order to better navigate complex and changing circumstances.

Chess is a great example. As we sit there, we’re constantly checking the board for the strength or weakness of ours and our opponent's positions (the “observation” step of the OODA Loop). We might scheme up the perfect plan to have the enemy king checkmated in three only for our opponent to make a totally unexpected move. While a bad player will stick to their original strategy (even though it’s probably no longer the most effective), a stronger player will quickly adapt their moves to the new positions on the board.

That same principle applies to the fluid grace you see in fencing and the verbal jiu-jitsu lawyers use – constantly adapting and re-adapting to a changing situation rather than doggedly holding to their original course (longtime readers might recognize that from the ancient philosophy of Taoism).

Again, this takes training.

As humans, we come into every situation loaded with preconceptions, assumptions, biases, blindspots, and an irritating resistance to change. Overcoming that means we need to consciously and deliberately develop our abilities to both discard tactics that aren’t working and find solutions in surprising places. The same way we need to be constantly assessing our situation, we need to be continuously questioning and re-evaluating our plans.

When a disruption happens, consider asking:

- Is this development actually a bad thing?

- Are there advantages here that I’m not seeing?

- What does my full list of options actually look like?

- Even if I think I have the right solution, what would be an unexpected solution to this problem?

Decide

Even if you don’t know the perfect choice, know the advantages of each.

Once we’ve managed to lay out our true range of options, we have to pick one – which isn’t quite as simple as it might look at first glance.

When we’re in fast-paced, high-pressure situations, one of the urges we’re going to have to conquer is the impulse to make a decision simply to have made a decision. Let’s be clear: making a random decision isn’t any better than stubbornly sticking to our original course.

Say that date night rolls around and while you were planning to show off with your homemade rotisserie chicken quesadillas, disaster strikes when your date casually texts you that they’re lactose intolerant just as you’re finishing up the dish. Being the bold man of action that you are, you ditch gooey, cheesy deliciousness and lay out your options.

You could dash to the store, find a cheese substitute, and rework your dish before the date arrives. You could wrap up the quesadillas for lunches throughout the week and try whipping up something new (time permitting). You could take the opportunity to send a flirtatious text back, asking what their favorite food is, and promptly ordering it via delivery.

No matter what circumstance we find ourselves in, there’s likely not going to be any single or obvious “correct” answer. The same way that we need to keep checking our situation in the “Observe” step and reassessing our plans in the “Orient” step, we need to evaluate the options we have for their potential pros, cons, and consequences.

In Boyd’s original graph of the OODA Loop, we’ll actually see the word “hypothesis” in parentheses beneath the “Decide” step – a good reminder that we’re not just picking an option to move forward, we’re anticipating a certain outcome and testing to see if our prediction was right (more on that in a second).

Although what metric we should use will vary from situation to situation, four that will apply to nearly every can be found below:

- Which option is the safest?

- Which option has the highest reward attached to it?

- How much effort/time/resources are you willing to invest?

- How much risk are you willing to take?

Which brings us at last to…

Act

Don’t just make a decision – learn from it.

It’s now or never.

We’ve taken in the situation, laid out our options, made our choice – now it’s time to put effort behind it.

Thanks to the previous steps in the OODA Loop, you’ll be able to commit to your hypothesis – whatever it might be – without hesitation, uncertainty, or second-guessing. Being able to filter our information through those preset checklists will mean we’ll be setting things in motion while the people around us are still trying to grasp what’s going on.

But that’s not all there is to it.

While the fourth stage of the OODA Loop is putting our final choice into action, it’s vital to realize that we’re not simply performing that decision – we’re actively testing it.

We’re keeping our attention focused on the here-and-now, trying to determine how our actions have changed the situation. It’s the difference between a champion boxer taking a calculated jab at an opponent and someone swinging a wild haymaker in a bar fight. One is maintaining a razor-sharp awareness of how the jab has been dodged and the other isn’t allowed back at this Chilis anymore.

Simply stated: don’t just act – analyze. Even if our decision didn’t have the intended effect, learning from it should still put us in a better position than before. Which brings us at last to…

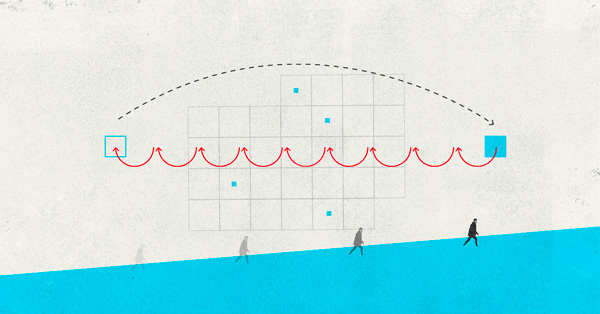

Loop Back Around

Analyzing the success or failure of our action should lead us back to the beginning of the process, where we’re running another orientation of our entire situation to see how things have (or haven’t) changed. In turn, that lets us run through our analysis again, sorting out our options and making another decision (bring us back to the “Observe” step once more).

Only this time, we’re moving quicker.

Hitting on the Half-beat

“Hitting the opponent on the half-beat” in the OODA loop refers to the belief that if you can complete the OODA loop more quickly than your opponent, you can influence their decision-making and gain the upper hand. The term “half-beat” specifically describes the situation when your opponent is midway through their Orient phase but has not yet made a decision. At this stage, you can “hit” your adversary to influence their decision-making and force them to restart the OODA cycle, which puts them at a disadvantage.

When it comes to decision making, especially during a crisis, Boyd believed that success wasn’t about making smarter decisions but making those decisions at a faster tempo than our opposition (whether that’s a person trying to foil us or a situation threatening to overwhelm us). Treating the OODA as a loop we’re continuously performing, rather than a process with a set end-point, helps us build off of each decision we make with ever-increasing momentum.

When emergencies arise, we’ll be the ones to spring into action. When the people around us are looking for leadership, we’ll be able to step into that role. When absolutely everything is going wrong, we’ll be the ones to find a way forward.

Don’t just survive chaos and uncertainty – overcome it!

What strategies and tactics do you use to stay ahead? Share your best tricks and techniques in the comments!

Read next:

![It’s Time to Begin Again: 3 Uncomfortable Frameworks That Will Make Your New Year More Meaningful [Audio Essay + Article]](https://www.primermagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/begin_again_feature.jpg)