For nearly six years, I struggled to get myself back into being a gym person.

Rewind to around 2018. I was about 34 then, and I was in the best shape of my life. I knew it was possible to be fit because I’d done it already, which made my inability to do it again feel even more insulting. But it was like trying to remember a password I knew I had used successfully for years, only to be locked out, over and over, until my computer started suggesting I contact the administrator (who, in this scenario, was also me).

I tried to restart, repeatedly, and couldn’t. I’d manage a workout here and there, just enough to remind myself what soreness felt like, and then I’d disappear again.

And the whole time, one thought kept looping in my head:

I’ve done this before. Why can’t I do it now?

In hindsight, I can admit what powered a lot of it: I was single and wanting not to be.

The times throughout my life that I was consistently exercising, I was also single. Not every stretch of singledom turned me into a gym rat, I had plenty of lazy bachelor phases too, but when I was motivated, I also happened to be actively dating.

I wanted to feel proud of how I looked, like if I was in better shape I’d be more likely to attract the kind of partner I wanted and to get those mental health boosts that come with regular exercise. That combination can make a man do almost anything. Including waking up early to deadlift.

During that era I was fully invested: going to the gym all the time, running on the track, and eating healthier (fewer midnight frozen pizzas, at least). I followed workout plans written by Brad Borland, Primer’s resident fitness guy, a natural bodybuilder and former military man with a master’s in kinesiology. I stayed consistent, saw results, and eventually got to a place where I was genuinely proud.

But then that chapter closed. And it turns out, “become more attractive” when the “…because I’m single” is scratched out isn’t a renewable resource.

After that high point in my mid-30s, I hit a long stall. I tried everything. Different gym memberships, home workouts with the weights left out the night before, lowering the bar to “just going is good enough”.

None of it stuck.

And when I’m not exercising consistently, my diet starts to resemble that of a raccoon in a dumpster. Bread everything. Cabinets open, Nutella from the jar.

Exercise was the anchor habit. Without it, the wheels came off elsewhere.

Part of the issue was a classic guy delusion: thinking I could just go back in, do the same routine, but you know, with marginally less weight given time has passed. Spoiler, I couldn’t.

Every time I tried to do “what I know worked before” it felt brutally difficult mentally.

Walking out of the gym feeling defeated made it really hard to convince myself to go back.

I blamed it on my willpower. Or that I wasn’t disciplined anymore.

But turns out, I was also aging, and so were my motivations.

Men Lose Muscle Mass Starting In Their 30s

By the time you hit 30, most men start losing 3 to 5% of muscle mass per decade if they’re not strength training. At 40, it’s closer to 1% per year. Jumping back in doesn’t just feel harder, it is harder.

At my peak, being in shape was tied to dating, confidence, opportunity, and identity. Now that I wasn’t single, that underlying drive was just gone, and “health because you should be healthy” was not strong enough to get me to the rack to do squats.

I kept trying to brute-force it with habit tricks and it didn’t work because I was trying to fuel current actions with outdated reasons.

And it wasn’t until that started to register that I could even ask the next question that ultimately led to the course correction:

Why do I want to exercise now?

A couple things happened at once.

One: I’d catch a glimpse of myself in the mirror getting out of the shower, and… I didn’t love it. Meanwhile, my now fiancée still looked as good or better than when we met. I didn’t feel good about the sense that I was unintentionally catfishing her: meeting her at my best shape and then sliding into some of my worst so quickly.

Bodies change, sure. Nobody looks like they did at 35 forever. But it matters to me that I don’t drift into, “welp, you’re stuck with me,” while I prioritize everything except my health.

Just: Am I exercising? Am I trying?

And I wasn’t. And we weren’t even married yet.

That didn’t feel good.

Two: my dog Leela turned 12. She’s a large, barrel-shaped girl with the grace of a squirming beanbag chair. The bathtub is high and has a deep ledge so she can’t get in or out on her own, even with some step contraption. I have to pick her up to put her in and take her out and one weekend when bathing her the awkward tub shape and her weight emphasized that I did not have enough strength to hold and maneuver her outside of a burst.

That hit in a new way. I realized I want to be strong enough to care for my loved ones. To carry Leela if her legs give out on a walk and she can’t get them going again. To help her up the stairs so she can participate and not stay on the first floor for the rest of her life. She’s part of my life. I want her to stay part of my life.

And realizing I probably couldn’t and wasn’t actively working on it? That felt sad.

So around last January, during my end-of-year reflection process that we always talk about on Primer, I took inventory. Other areas, mental health, finances, family, career, had at least some attention.

Fitness had basically none. Like I had completely opted out.

And I wrote down something simple: “I want to feel like I am a person who exercises.”

James Clear, the Atomic Habits guy, talks about three layers of behavior change: outcomes, processes, identity. Identity is the deepest layer. “Every action is a vote for the type of person you want to become.” I didn’t need to win a bodybuilding trophy. I needed a vote.

But it still left a practical question: how do you measure identity?

It’s not like you can say, “Okay, done, I’m a gym person again.” I didn’t care about signing up for a marathon. I didn’t care about a one-rep max. I cared about becoming consistent.

So I needed a goal that was measurable and realistic enough that took into consideration the struggle I had getting back into it.

Around that time, I was talking to my friend Ryan Masters, who has been jacked since I met him 12 years ago. He has meat slabs that fold over on themselves where his chest is supposed to be.

I told him what I had been thinking and he told me the approach that had been working for him:

Instead of his goal being number of workouts, or specific body weight, it was total hours in the gym per month. He still tracked what he did and how much he would do for each exercise, but that was so he could know how much to do. Those weren't his goal.

Just total time in the gym each month. That was it. Not reps or progression. Minutes.

And this wasn’t coming from someone dabbling back in after a long break. This is a guy who knows how to train, who’s built consistency over years, who’s done hard things just to see if he could. Which made the whole thing land differently. If someone with his background found real value in using time as his goal, maybe there was something to it.

If I wanted to feel like “I was a person who exercises” as a part of my lifestyle, how many hours per month would I have to exercise to feel like that?

So I stole the idea immediately.

Then I chose a number.

As our piece on how to set short-term goals that work explains, a good goal is S.M.A.R.T.: Simple, measurable, attainable, relevant, and time-bound.

I didn’t choose an aspirational, heroic number. I chose a number that felt almost too easy, because I wanted something attainable I could hit even on my worst month:

4 hours per month for every month last year.

Yep. Four hours.

That’s about an hour a week total. It’s low on purpose.

Back in my peak days I was training 3-4 times a week for 40-60 minutes a session, easily 12+ hours a month. But I wasn’t that guy anymore, and I needed to start from where I was now.

With 4 hours a month, you can do:

- 9–10 25-minute workouts

- 5 45-minute workouts + a little extra

- 16 15-minute workouts

- One super workout and random short workouts that add up

It didn’t matter how I got there, as long as the minutes accumulated.

To track I used a free time-tracking app called Toggl. I’d tap “Start” when I began exercising and “Stop” when I wrapped up. I created an “Exercise” project in the app that my time entries were assigned to which meant I could easily see my progress as the month went on.

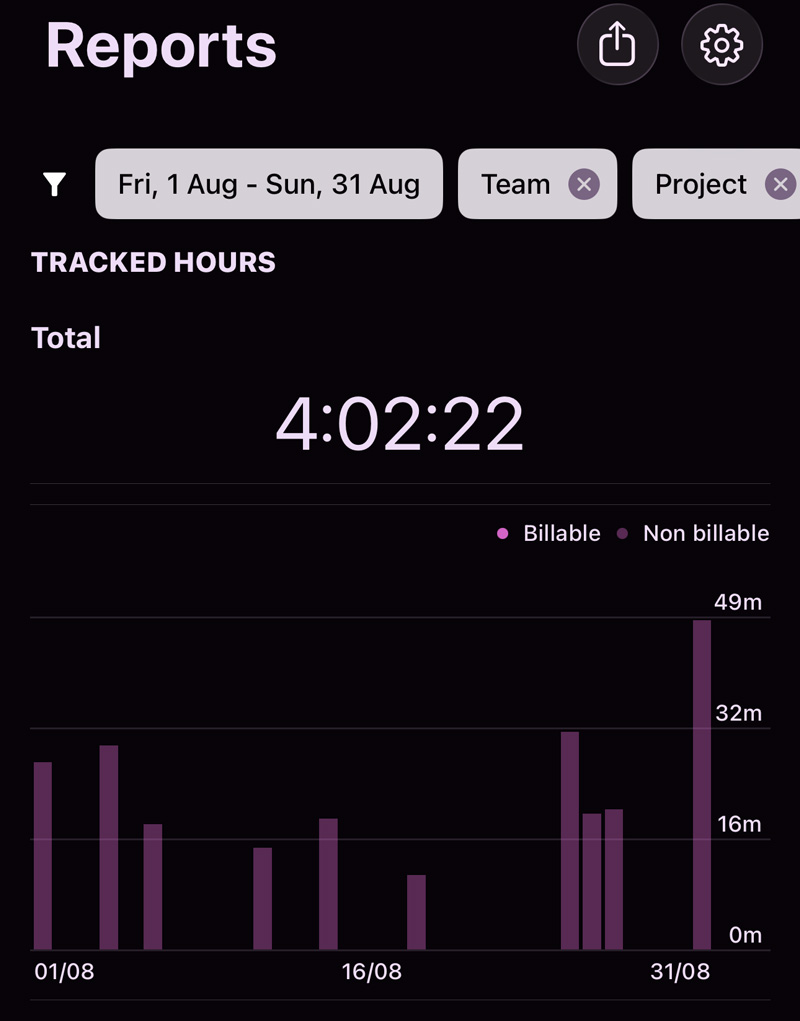

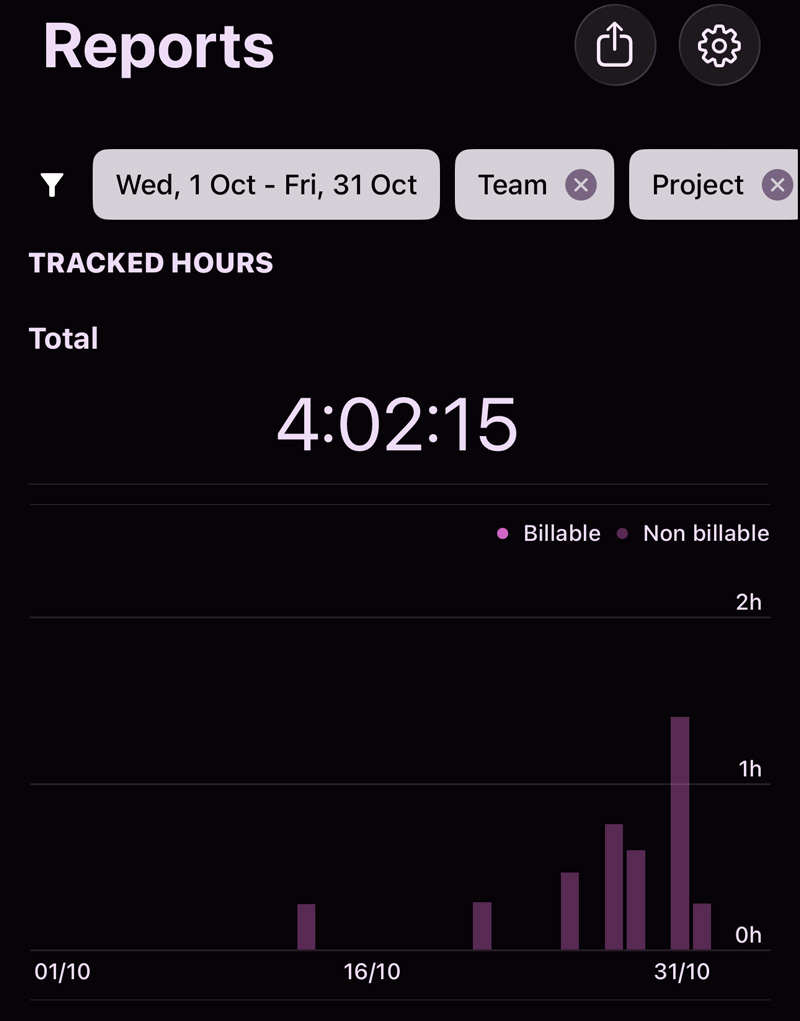

Two screenshots from Toggl showing two very different patterns for accomplishing the time goal:

What counted (and why that mattered)

One thing I decided early: As long as I was setting out “to exercise” before I started, it counted toward the time.

That included:

- strength training at the gym

- going for a run outside or on a treadmill, bike, rowing machine

- Inviting friends to play pickleball on a random Saturday

- workouts while traveling, even if it was short and in a hotel gym

This was the key mental shift:

Every minute counted.

That meant I stopped beating myself up for short workouts or ones that didn’t involve a metal plate. Even a 12-minute workout was still a win because I showed up.

Some days I would walk into the gym feeling blah and literally do three sets of squats (an exercise I despise) and walk right out.

In the past I’d have thought, what’s the point of even going for 12 minutes?

Under this system, 12 minutes had a point: It was 12 more minutes towards my goal, and it was proof I was still in the habit.

I even traveled to Hong Kong in April and still got my hours in using the hotel gym for 20 minutes at a time.

In the past, travel always derailed me. Now it didn’t, because I wasn’t chasing a perfect workout or schedule. I was just stacking minutes.

Also, once I had the habit, intensity started improving naturally.

By the second and third month I found myself increasing the weight or adding an extra set. I felt good and wanted to push more.

But I never made it a requirement.

The requirement was time. The habit came first. Evolution happened naturally.

The receipts: why it worked

I’m proud to say I hit that 4-hour goal every month last year.

It might not sound like much to fitness enthusiasts, but considering I’d spent years struggling to do anything consistent, it felt like a real victory.

And surprisingly, after only a month and a half in, I already felt like I’d achieved the actual goal:

“I felt like a person who exercises.”

The identity shift happened faster than I expected because the goal was so manageable that I stopped dreading exercise. I stopped overthinking it. And started contributing minutes to it.

It also fixed a big problem I always had with workout plans: if you have a goal to workout 3x per week, it’s easy to get to a certain point in the week, feel behind, and just toss that week up as a loss. Why still get 1 workout in if you only get credit for 3?

With a monthly hours goal, it was never too late to catch up.

If by the 15th I’d only logged one hour, no big deal. I still had half the month to chip away. I could do 20 minutes here, 20 minutes there, and still hit 4 hours. Heck, in a worst case scenario you could get all 4 hours in on the last day of the month if you split it up throughout the day. Still getting credit and likely jumpstarting the start of the next month.

The takeaway: steal this

If you’ve been struggling to become a person who exercises, or if you’re carrying the weird shame of once being fit and now not being able to get back there, I strongly encourage you to try a monthly exercise time goal.

Here’s how to do it:

- Pick a tiny monthly number you’re confident you can hit even on a bad month 2 hours, 4 hours, 6 hours. Start low.

- Decide how long your streak will be. You could do all year or two months at first.

- Track it. Toggl is free and makes it easy, and by setting up an “exercise” project, you can easily see a report of total time logged right in the app.

- Let all workouts count. Intense ones. Lazy ones. Short ones. Long ones.

- Adjust without guilt. If you find yourself beating your goal, amazing! If you picked 12 hours and it’s just not realistic, recalibrate. Don’t scrap the system.

A year ago I was the guy who wanted to work out but didn’t.

Now I’m a guy who works out regularly (even if not spectacularly).

That change didn’t require a health scare or breakup or some training movie montage. It happened a few minutes at a time, month after month.

And if it can happen for me at 41, it can happen for you too.

All it takes is a goal small enough to hit, and a willingness to keep showing up, minute by minute, until one day you look up and realize:

“Hey. I’m doing it. I’m back.”

![It’s Time to Begin Again: 3 Uncomfortable Frameworks That Will Make Your New Year More Meaningful [Audio Essay + Article]](https://www.primermagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/begin_again_feature.jpg)