There’s no escaping it — you will negotiate everything.

You’ll negotiate your pay raise, you’ll negotiate your performance review, you’ll negotiate the car you’ll buy or the wheat you’ll trade for sheep in Settlers of Catan. Regardless of your job or place in life, you will eventually find yourself pitted against your fellow man in a battle for your own best interests. That might mean haggling with a salesman or standing up to your boss or debating the cop who takes issue with you riding your ostrich down the HOV lane. One way or another, you are going to have to fight for yourself.

So why not fight to win?

Anchoring in Negotiation

Always make the first offer. Always.

That might sound strange — maybe even blatantly wrong. Make the first move? Aren’t you supposed to play things close to the chest when it comes to serious bargaining? Isn’t throwing out the first offer going to make you look too eager?

Not at all.

Contrary to what you might think, making the first offer gives you a massive advantage in any negotiation. Rather than “showing your hand,” you’re effectively setting the stage for the entire conversation — tethering the debate to the first number you throw out.

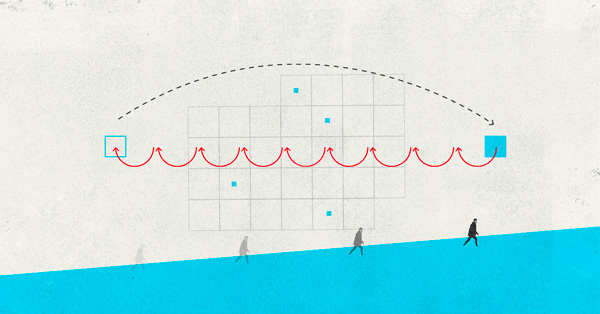

As Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman point out in their study published in the journal Science, “Anchoring” (sometimes called “focalism” or “the adjustment heuristic”) refers to the way our highly fallible minds tend to produce wildly different conclusions based on the order in which data is presented. Simply put, the squishy lie factories in our skulls will tend to cling to the first piece of information they get If that sounds confusing, try thinking of it this way:

Imagine walking into a garage sale and seeing a blanket. No, the blanket. The warmest, comfiest, most aesthetically goddamn pleasing piece of fabric you’ve ever laid eyes on. You stride boldly up to the proprietor and tell him you’ll give him 30 bucks for it.

Here’s the kicker:

The proprietor might’ve been hoping to sell that very blanket for twice or even three times what you just offered, but by you throwing out 30 dollars, you’ve effectively “anchored” the dialogue. Now every counter-offer is going to be consciously and subconsciously compared against that starting point. The result? The proprietor may try working you up to 40 or even 50 dollars (it’s still a negotiation, after all) but they probably won’t drift too far from where you began.

Now you might wonder, “What if I offer five bucks for something when the other party would’ve sold it for a buck?” While that is a possibility, it’s important to keep your own goals in mind. The other party leaping at your offer might mean they would’ve settled for even less, but ultimately, what matters is that you buy or sell for a price that you’re comfortable with. A win for you doesn’t hinge of bleeding the other side for every penny.

But what if they fight back? While the other party may attempt to counter that move by emphatically stating their own ideal price (“It’s ninety bucks, kid!”), research shows that even people aware of this technique have a hard time shaking this cognitive bias. That’s the infuriating power of anchoring — just having that number floating around in your head will implicitly shape your judgments (and it works just as well in reverse).

If you’re selling something (a car, for example), throwing out a high starting price will skew the range of outcomes to the upper end. And that’s not all. Anchoring has the added effect of pressuring us to justify the supposed cost of the item in question. A high starting price will draw our attention to the positives (like the impressive fuel economy or how the AC feels like wind off a Norwegian glacier).

At the same time, a low starting price will emphasize the negatives (the suspension that shrieks like tortured witches or the way the seats smell of day-old chili). As rational as you might like to think yourself, nobody’s immune from their own hardwired biases. Fighting for you’re ideal price? Science says to swing first.

The Lesson: While it can feel like you’re giving a way your hand, establishing the starting number gives you an incredibly strong position from which the rest of the negotiation works from.

Reciprocity and Negotiations

While you’ll find the occasional, incorrigible moocher out there, the simple fact of the matter is that humans have a desperate and deeply-rooted need to be even. “Give-and-take” is ingrained into our society and our psychology – an “internalized social norm” to use the words of researchers in the European Journal of Personality – whether that’s Hammurabi’s code of “an eye for an eye” or Dwight and Andy desperately trying to settle their social obligations (seriously, that clip is about as brilliant a demonstration of this technique as you’re ever going to find). Get a gift from someone? Well, you’re likely going to feel compelled to buy a gift for them in return. If someone picks up your tab you’ll probably feel awkward until the scales are balanced. Hell, anyone who ever scuffled with a sibling as a kid knows the “we-have-to-be-even” rule when it comes to punches and kicks.

The guilt and petty politics of socials debt can be a nightmare. But when it comes to negotiations, reciprocity can be used to give yourself some serious leverage, especially if you’re smart about it. Marketing and persuasion expert Robert Cialidini found that waiters offering their patrons an after dinner mint increased tips by 3%. For wait staff who added, “for you nice people, here’s an extra mint,” tips jumped by a whopping 23%.

This isn’t just for beguiling the other side, but for guilting them as well. Katherine Shonk, editor of Harvard Business School’s Negotiation blog, asserts that you should be specific about the things you’re giving up. Why? Well, in spite of people’s instinct to be even, you can’t always count the opposing side recognizing when you’re making a compromise or how important of a point you’re folding on. Getting a fair deal means making people understand exactly what you’re exchanging. As strong as reciprocity is, to really make it work for you, you need to make the exchange felt for it to have any effect.

There’s a dark side to this, too.

Imagine you’re on the phone with a vendor, desperately trying to hammer out a deal. You might say something along the lines of, “Look, Marcus, I’m willing to give up my request for free shipping, okay? And I’m not going to ask for the decorative packaging but you gotta give me something here…”

Now does Marcus have to give you something? Well no, not technically, but thanks to a deeply-rooted sense of social obligation, Marcus will probably feel pressured into making some kind of concession.

That’s all relatively standard for the back-and-forth of bargaining (though it does help to be aware of it), but if you’re looking to pull an especially Machiavellian move, you might consider the following strategy: give up the things you don’t want.

You might complain to Marcus that you’re giving up free shipping, but did you even want it to begin with? Not at all. You factored shipping into your budget from the beginning and your niece’s birthday nunchucks (because you’re a cool uncle) are going to be wrapped in that glittery paper you already bought (she only turns five once, after all). Still, claiming you’re “giving these things up” is going to goad Marcus into sweetening an already passable deal. Is that a dirty trick? Absolutely – and whether you feel comfortable using it is entirely up to you.

What you should remember, however, is there’s a good chance other folks won’t be as conscientious. Learn to recognize when someone’s trying to use reciprocity on you. When it comes time to compromise, you should always ask yourself: Am I reaching out because I want to, or because I’m up against the ropes?

The Lesson: Parties will cultivate courtesies and favors as a way to make you feel obligated to concede or compromise in some way.

Separating Wins and Merging Losses

While most textbooks and stock photos are going to portray negotiations as a bunch of well-groomed, impeccably-suited people smiling and shaking hands in brightly-lit offices, chances are that won’t be you.

As much as you might wish otherwise, haggling doesn’t usually happen on a level playing field. While there will hopefully be times when you’re holding all the cards, the harsh reality is that you’re more likely to be working with limited chips to bargain with (and limited time to do it). As if that wasn’t bad enough, the people you’ll be up against — from your supervisor at work to your landlord at home — will know that you’re coming from a low-power position. So what do you do when you’re punching above your weight class?

You make yourself look stronger than you actually are.

While you can’t conjure resources out of thin air, writers at Harvard Business School’s Program on Negotiation are that you can present your concessions in a way that makes them seem twice as valuable (or the opposing side’s compromises being half as painful). Thanks to what behavioral economist Richard Thaler terms “mental accounting” (the often-irrational way people categorize their gains and losses), you can bulwark your position simply by framing the details of the deal in a certain light.

Think of it this way — which would be more irritating? Getting a bill from your utility company for seventy-five bucks, or getting one bill for twenty-five dollars on Monday, another bill for twenty-five dollars on Tuesday, and still another bill for twenty-five dollars on Wednesday? Even though both scenarios total to the exact same number, you’d almost certainly find the latter option infinitely more infuriating.

According to researchers Deepal Malhorta and Max Bazerman, the same principle works in reverse.

If you were to find five bucks in your pocket one day and another five bucks in your pocket the day after, you’d probably be happier than if you found a single ten dollar bill (that, and you might start to think your jeans are magical).

Now that might seem obvious, but when it comes right down to it, merging losses and separating wins is one of the most astonishingly effective (and agonizingly underappreciated) bartering tactics out there. You might be dealing with a demanding client who keeps pushing for more and more markdowns. If there’s an absolute limit to your lowest price (and as Harvard points out, you should have a limit), don’t despair. Try breaking your discount apart.

You might say: “Okay, Fred, you’ll be saving 50 dollars on labor thanks to your premium membership status. And you’ll be saving another 50 thanks to the trade-in value. And we’ll be giving you the extended warranty, which is eighteen months instead of twelve – that’s another 100 dollars right there.”

Even though that equals out to the same 200-dollar leeway your supervisor’s authorized to you to offer, the effect is that Fred feels like three times the winner (and thanks to reciprocity, more likely to cut you some slack).

On the other hand, you can soften the blow by carefully bundling costs. While an itemized invoice is probably inevitable, when it comes to dealing directly with the other side, you can convince them they’re giving up less by consolidating their compromises. Instead of saying “Well, it’ll be 20 for the supplies, 80 for the manpower, and 60 because your pet iguana got loose and attacked one of our technicians” you’ll likely be better off simply saying, “it comes to 160 even.”

This may seem surprising, but as Malhotra and Bazerman’s research points out with their back-to-back money finding example, people are more upset losing $10 two days in a row, than losing $20 on one day:

As these results demonstrate, people seem to prefer receiving money in installments but losing money in one lump sum. The potential relevance of this effect to psychological influence in negotiation is easy to articulate: Negotiators can disaggregate the other side’s gains to maximize total pleasure and aggregate the other.

The Lesson: The mind has a funny way of interpreting value and loss by combining or separating items and numbers. Knowing how to use that intentionally can be a very powerful asset in any negotiation.

And as effective as that can be, always remember…

You Have To Pick Your Negotiation Battles

For all the dastardly devices and sinister strategies out there, there will be times when there’s simply no “zone of potential agreement” (that is, no overlap between the maximum you’re willing to pay and the minimum the other side will settle for). Even equipped with every dirty trick in the book, there’s no better skill when it comes to haggling than knowing when to walk away.

No matter what you might hear, there’s no shame in playing it smart and no sense in sinking your valuable time and energy into a stalemate, especially in situations where you have no leverage or the results aren’t all that significant. Victory — real victory — sometimes comes down to being able to pick yourself up off the ground with enough strength to slug it out again tomorrow.

No, you can’t win ‘em all. But armed with the right knowledge, you can give yourself a fighting chance to win the ones that count.

The Lesson: Above all else, negotiation needs to serve some purpose. Bargaining out of habit or obligation is a waste of energy and time.

Read now: The Ultimate Bag of Dirty Tricks for Salary Negotiation

What devious mental devices have you used to get the upper hand in a deal? What tricks and traps have you had to watch for? Keep the conversation going in the comments!

Illustration by rawpixel.com

![It’s Time to Begin Again: 3 Uncomfortable Frameworks That Will Make Your New Year More Meaningful [Audio Essay + Article]](https://www.primermagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/begin_again_feature.jpg)