For men in the Northern hemisphere, it’s time to start considering our sartorial options for fall and winter. Whether he opts for custom and is factoring in the time it takes to create a garment, or just wants to get ahead of the curve, the warmer months of fall are the ideal time to start making purchases for the cooler times ahead.

There are hundreds of choices to be made when dressing for colder temps, and one of the largest is the ideal material. Obviously weight, heat retention, waterproofing are all to be considered, but other factors such as comfort, history, and respectability need to be considered as well.

One of the most common materials seen on well-dressed men in autumn and winter is flannel.

While no one knows its true origin, historians believed it was invented by the Welsh as early as the 16th century. During the 17th century it became the fabric we know today.

Contrary to popular belief, it is not a particular type of material or pattern, but a way in which a material is treated. Flannel is most commonly found in wool and cotton, although synthetic materials have been used to make flannel as well. First, the yarn is spun loosely, creating the softness for which flannel is known. From there, it can be treated in three different ways. The first is to leave it as is. The second and third involving a process called napping. This is done by brushing either one side or both of the fabric with a fine metal brush, creating fine fibers from the loosely spun yarns. All three results can be considered flannel, but all three will vary in texture and softness, with a double nap being the softest.

Trim fit flannel from Duluth Trading Co.

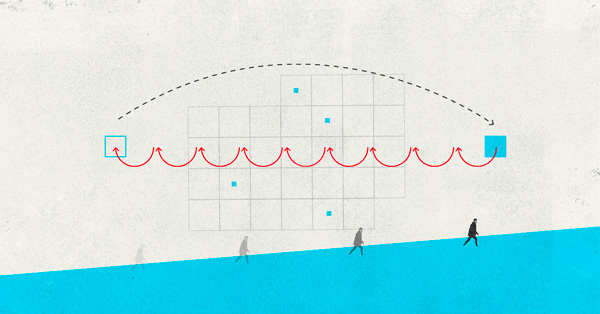

This process is what makes flannel ideal for colder months. Unlike other cloths that rely on a fabric’s density or weight, the air pockets created with flannel are its advantage.

Think about climbing into a bed with flannel sheets at the end of the day. The reason this cloth feels warmer than a regular set of cotton sheets has to do with the science of heat transfer. Unless a man is prone to keep his home at 98.6 degrees, any object that is room temperature is cooler than his body. When lying down on a typical jersey sheet, the amount of skin surface area touched by the sheets is significant, and this higher surface area leads to more heat transfer. More skin-on-sheet contact means there is more heat transferred from the warm skin to the cool sheets. On the other hand, the finely woven fibers and open weave of flannel create empty pockets of air. Not only does this decrease the surface area and amount of heat being transferred from the skin to the cloth, these little air pockets heat up quickly and act as an insulator. It sounds backwards but the reason flannel feels warmer is because the cloth sucks away less heat. And what it does draw away is retained in little air pockets that keep the air warmer than the fabric itself.

Body heat retention is a classic way of making clothing warmer and more comfortable.

While the typical association for flannel is a Tartan or Plaid pattern (thank you Nirvana, Pearl Jam, etc.), it can be dyed in any pattern or color the mill chooses.

Flannel doesn't have to be plaid. Lands End, $49

Another advantage of flannel is how well it spans the formality spectrum of men’s clothing. It can be used for something as casual as pajama bottoms, or be made into the highest quality, winter-appropriate suits. Unlike other materials like linen or weaves like hopsack, it doesn’t reside solely in the territory of formal or casual clothing.

So, whether a man needs to dress for business meetings or sick days, flannel should have a solid and consistent place in his wardrobe.

![It’s Time to Begin Again: 3 Uncomfortable Frameworks That Will Make Your New Year More Meaningful [Audio Essay + Article]](https://www.primermagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/begin_again_feature.jpg)