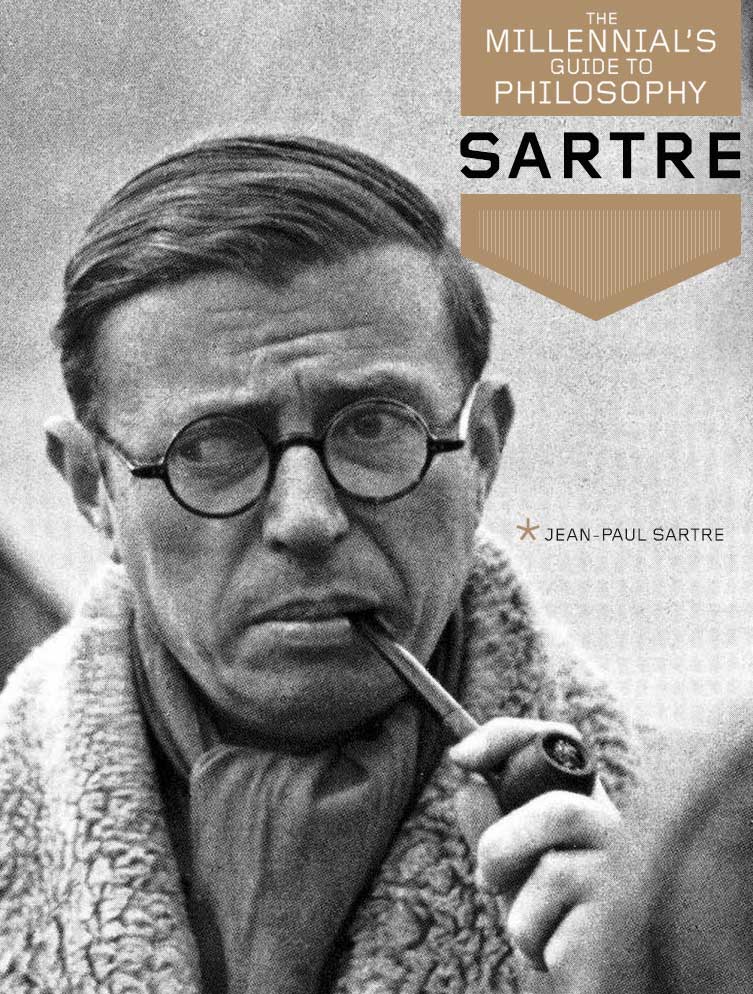

He and his equally brilliant girlfriend scandalized polite society with their open relationship. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, only to turn it down. His house was bombed by nationalist terror groups not once but twice. He rubbed shoulders with freedom fighters and film stars, athletes and activists, painters and politicians. Even to this day, his image overshadows his ideals, and many of us might know the name “Sartre” without knowing what it was he stood for.

That changes today.

Who He Was

Born to a middle class French family in 1905, Jean-Paul Sartre spent his early life as an academic and a writer. Though a well-liked prankster, a modestly successful college teacher is perhaps all he would have been had he not been drafted by the French military in 1939.

Shortly after his service began Sartre was captured by Nazi forces and placed in a prison camp where he spent nine miserable months. Although finally released, that time as a POW had a profound effect on Sartre, giving focus to his theories and catalyzing his growth as both a thinker and a radical.

In less than a month of his release, Sartre returned to France to organize resistance to the Nazis and the Vichy regime. And while his comrades sabotaged rail lines and skirmished in hinterlands, Sartre set his crosshairs on a much more insidious enemy: the ideology of tyranny itself. It was a battle he would fight for the rest of his life, and Sartre’s revolutionary principles of responsibility and freedom continue to shape the modern world in a way no tanks or trenches ever could.

What He’s Here To Tell Us:

The purpose of philosophy is to offer us a way of making sense of the world we live in. As the world is a pretty damn big and complex place, philosophers can themselves sometimes be a bit tough to understand and that’s definitely true of Sartre. If we’re going to understand his profound insights and apply them to our own lives, there’s two key terms that we first have to grasp:

Existence and Essence

“Man simply is.”

– Jean-Paul Sartre, Existentialism is a Humanism

That might sound strange at first, but what Sartre is communicating here is actually a surprising way to understand how we, as humans, differ from everything else in the world.

Imagine, for a moment, that you need a place to store your books. While most of us would simply go out and buy a bookcase, you – being an industrious and enterprising person – decide to make on yourself. You’ll figure out where you want the bookcase, how large it should be, how many books it should be able to fit, and so on – all of that before you assemble your shelves.

That carefully laid-out plan right there is the shelf’s nature and purpose, its “essence.” From here on out, you can judge the shelf’s value by how well it fulfills its function and matches your blueprint. The same goes for chairs, cell phones, boots, pickup trucks, pianos, aircraft carriers, those weird table-things they stick in the middle of delivery pizzas to keep the lids from mushing the cheese – you name it. Everything humans make is created from a design to serve a purpose.

But what about humans themselves?

For Sartre and his fellow existentialists, the answer was a resounding no.

“Existence,” Sartre argued, “precedes essence.” Humans are thrust into the world without an inherent nature or purpose, (i.e., the essence of your book shelf). There’s no pantheon of gods to pull the strings. No mysterious, pre-ordained fate. No natural hierarchy or universal order. As a line from Rick and Morty puts it: “Nobody exists on purpose…”

Now, Sartre recognized that thought can be jarring. Human anxiety (what he dubbed “anguish”) came from forging our own ways in the world without any instruction manual on how you should be. As terrifying as that can be, however, Sartre insisted that it could also be utterly liberating, freeing us from those who would insist our lives are preordained or constrained by our race, nationality, gender, or genes. A bookcase can only ever be a bookcase. You are both the person you are right now and everything you could potentially become as well.

So where does that fundamental lack of constraint leave us? What should we do with our freedom?

According to Sartre: Choose.

Bad Faith

“I am condemned to be free.”

– Jean-Paul Sartre, Being and Nothingness

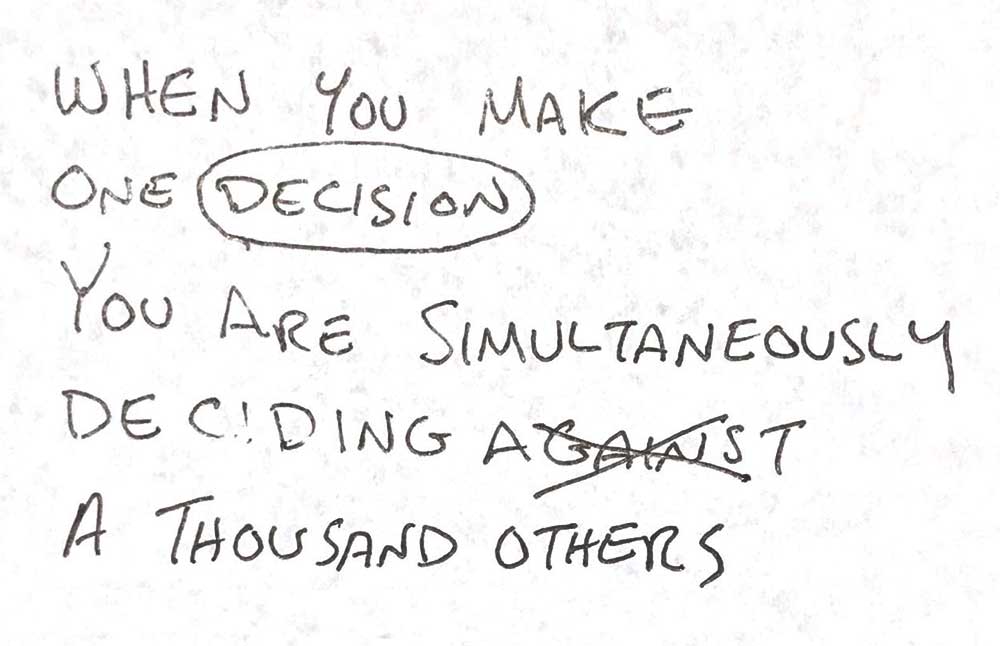

Given the opportunity to do anything, go anywhere, or be anyone, the response many folks have is to simply be nothing. And that’s understandable. Freedom, as much as it gets praised, is pretty scary – hell, it’s downright terrifying sometimes. When you make one decision, you’re simultaneously deciding against a thousand others. Faced with that pressure, that immense responsibility, plenty of folks shut down, deluding themselves into believing that they aren’t the masters of their own fate. They simply hunker down and hope things will fix themselves, or that someone will decide for them.

How many times have you heard someone grumble something along the lines of “I hate my job but I can’t leave it”, “It’s too late for me to quit smoking”, “I’d join the resistance against our demented mutant squirrel overlords but I have to provide for my family.”

That, Sartre tells us, is self-delusion, a grotesque misuse of our freedom to deny ourselves freedom. He called it “bad faith,” and it means people spare themselves from making choices or accepting the burden of responsibility, but ultimately makes us more miserable than any decision ever could. If people were honest with themselves, they’d see their actual circumstances. “I hate my job but I choose not to leave it,” “I choose to keep smoking,” “I choose not to endanger my family by resisting the mutant squirrel overlords.”

Now that isn’t to say that you have control over your situation. Sartre, a former prisoner of war and lifelong anti-colonial activist, understood that there are very real limits upon the options we have. A lack of control, however, is not the same as a lack of freedom, and from that there is no escaping. As legendary prog rock band Rush tells us, “If you choose not to decide you still have made a choice.”

Authenticity & Responsibility

“In fashioning myself, I fashion man.”

– Jean-Paul Sartre, Existentialism is Humanism

Sartre understood freedom not as a lack or absence of responsibility, but the fullest acceptance of responsibility. Responsibility for one’s place in life, for the sum of the choices you’ve made, and for the all choices you didn’t make. That can be a tough burden to bear, and it’s about to get tougher. Not only are you condemned to be accountable for your choices, but the decisions you make represent what you believe everyone on earth should be.

Think of it this way: If you make a decision, then you should believe that it’s the right decision. If it’s the right decision, then you should believe that anyone in the same situation should act the same way. There’s no room for hypocrisy, exceptions, or double-standards – no “it’s alright for me to do this, but not for anyone else.”

Rather than freedom giving you the ability to act without consequences, Sartre expects that a truly sincere person will essentially lead the world by example, setting the standard with their own life on how they think a person ought to be. Like it or not, your actions convict you as much as they define you, and if you can’t stand by your decision defiant and proud, then perhaps it’s not the decision you should be making. That’s authenticity and as Sartre saw it, it was the only life worth living.

What It Means For Us

The freedom that comes with the first years out of college can be exhilarating, but it can easily be overwhelming as well. Those of us recently graduating might feel a very real pressure to figure out where we fit in – to find our proper place in the world or to prove ourselves as adults (the model of adulthood we’re given, at least).

Those of us who’ve been out a while might be tempted by the trap of bad faith, imagining ourselves to be forever shackled by our student loans or inextricably stuck in a career path or dead-end relationship. Awful, sure, but at least they spare us the agony of taking responsibility or making choices, right? Things will somehow work themselves out, won’t they? These rough patches are something we have to suffer though – even as bad days stretch into bad months and listless, meaningless years.

Think again.

Sartre doesn’t give us any excuses to hide behind. In those dark days, his existentialism can offer us some much-needed tough love, dragging us – kicking and screaming – out of our self-pity and back into the driver’s seat.

Once we understand that our futures aren’t written by anyone but ourselves, we can truly begin to break free from the self-made prisons of bad faith. It’s only when we take responsibility for our choices that we can live honest, authentic lives and put our true values into practice. Now more than ever, Sartre challenges us to honestly reconsider our lives and ask if, at the end of it all, we’ll be proud of what we undertook. Life isn’t measured by the things we might do, it’s measured by the things that we will.

So what’s it going to be?

Required Reading

Existentialism is a Humanism by Jean-Paul Sartre – Sartre’s billed his 1946 lecture as a defense of existentialism, but the end result is a combined manifesto, a seamless introduction to his thought, and a rousing call to action. Existentialism is a Humanism serves as a fantastic starting point for anyone interested in Sartre’s extensive body of work.

No Exit by Jean-Paul Sartre – In this legendary single-act play, Sartre offers us a haunting picture of three souls imprisoned in a surreal hell of their own making, trapped by their inability to take responsibility for their own actions. No Exit might be brief, but its lessons will linger on long after the curtains have fallen.

Nausea by Jean-Paul Sartre – Earning Sartre the Nobel Prize for Literature (which he turned down), Nausea offers a compellingly detailed glimpse into a young man grappling with the dizzying absurdity of the world around him. A foundational text for understanding Sartre’s work with a plot many of us will relate to all too well.

Read more:

The Millennial’s Guide to Philosophy

- The Millennial's Guide to Philosophy: Stoicism

- The Millennial’s Guide to Philosophy: Epicureanism

- The Millennial’s Guide to Philosophy: Nietzsche

- The Millennial’s Guide to Philosophy: Postmodernism

- The Millennial’s Guide to Philosophy: Confucianism

- The Millennial’s Guide to Philosophy: Taoism

- The Millennial’s Guide to Philosophy: Sartre

- The Millennial’s Guide to Philosophy: Kierkegaard

- The Millennial’s Guide to Philosophy: Camus

![It’s Time to Begin Again: 3 Uncomfortable Frameworks That Will Make Your New Year More Meaningful [Audio Essay + Article]](https://www.primermagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/begin_again_feature.jpg)