|

This content series is in partnership with smartwater. smartwater, live a life well hydrated. Click here to learn more.

What is this? |

If you feel stuck in a rut, I think I might know why.

Consider this:

Part I: Your Life in a Loop: Groundhog Week

From the day you are born, every single year is different. Your progress through life is tidily tracked as you go from grade to grade, from elementary school to middle school, from high school to college and beyond. Each year takes you one step closer to that next life changing milestone—getting your license at 16, becoming a legal adult at 18, becoming a legal drinker at 21. Through your mid-twenties, growing as a student, a citizen and a person in general is as simple as growing older. It happens whether you make an effort or not.

But a funny thing happens when you get out of college, get a job, get a place to live and/or get a steady long-term relationship. Whereas a year in the life used to be filled with 365 days of new ground, now, your days have become something else.

Suddenly you wake up and you say: “Today feels like a Tuesday.” How does a Tuesday feel? It feels like the day that comes before the day that feels like a Wednesday and the day that comes after the day that feels like a Monday. And the reason that these days all have a feel—a cozy niche within the week—is that you, sir, have fallen into a routine.

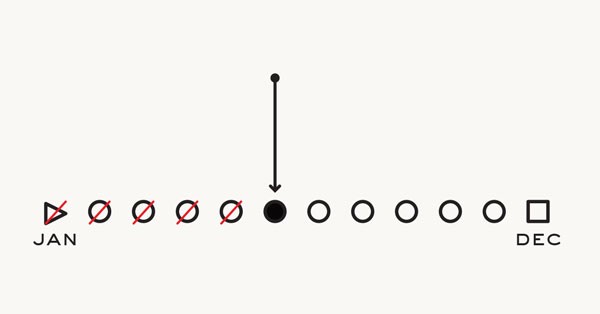

When life is steady, we stop measuring our lives in years. The unit of life becomes the week: Monday through Friday plus the weekend. We plan our chores and our social activities one week at a time, squeezing them in between the daily grind of wake, work, eat, sleep. If we are lucky and disciplined, we get to lead a fulfilling and engaging life between these margins. But if we are not, we end up living the same week over and over and over again. We island hop from weekend to weekend and before we know it, 52 weeks have passed and we are a year older.

And what do we have to show for it?

What we have is the cumulative impact of living basically the same week in a loop. Of course it doesn't always feel that way in the moment. There are always different fires to put out at work, different bars to hit up after work, different household chores to tackle, different episodes to watch on Hulu. But on average, when you boil everything down to their broad categories—time spent exercising, level of sexual activity, number of cigarettes smoked, hours slept, etc.—we are fairly consistent week to week. There are times when we binge a bit, or abstain temporarily, or have brief period of inspiration and motivation toward our big goals. But eventually, we wind back down to our usual routines. Part of the reason for this is that when the weekend rolls around, our brains have a screwy way of resetting the scoreboard. Every Monday feels like a fresh start. And we are quick to repopulate it with our old habits (more on this in Part II).

What It Means to Live 100 Years

When you’re living it, it’s hard to fathom what it means to live the same week over and over. But it’s not hard to quantify a rough estimate of the results.

Let’s say you are 25. Let’s say you plan on living 100 years. So, you’ve got 75 years left to go.

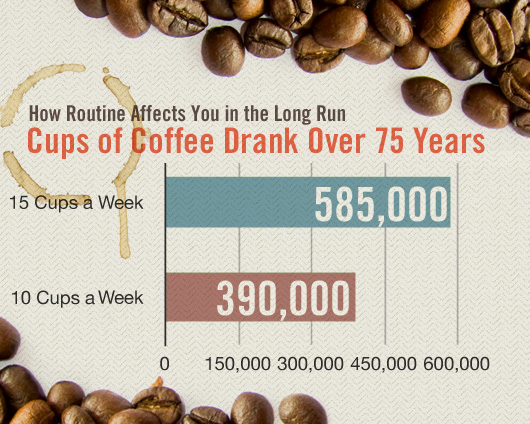

Let’s say you drink three cups of coffee on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday. That’s 15 cups of coffee a week, or 780 cups of coffee in a year or 585,000 cups of coffee in your lifetime.

Let’s say you smoke a pack of cigarettes a week. That’s 52 packs a year and, assuming you still somehow manage to live for 100 years, that’s 3,900 in a lifetime.

Let’s say you eat fast food four times a week. That’s 156,000 meals. That’s you, dying in your hospital bed, knowing you’ve eaten over a hundred thousand Big Macs.

Unless you’ve applied for a home mortgage, you probably haven’t seriously considered how things add up in the long run. But if you have, you know the secret about numbers stretched out over decades and decades: tweaking the weekly or monthly numbers can have a huge impact on the final sum.

Let’s say you drink one less cup of coffee each day. That’s 10 cups of coffee a week, 520 cups a year and 390,000 before you’re dead, which amounts to about 195,000 fewer than if you were drinking three cups of coffee each day.

I know cutting your caffeine intake by 33% is drastic, so let’s say you cut your weekly fast food average by just one meal. At three trips to McDonald’s a week, that ends up being 117,000 Big Macs, or a difference of 39,000.

Okay, but so what? Those are just numbers and those are just the little sundries of life that no one keeps track of anyway. While Big Macs, coffee and cigarettes are obviously not so great for your bod, these aren’t really the things we keep tabs on when measuring our overall level of happiness or our satisfaction from life.

Let’s take a look at those things.

What about the time we spend doing things that are meaningful to us. And what about the time we waste doing the things we hate or, just as often, doing the things that make us hate ourselves?

If your commute to work is 45 minutes each way, that’s 360 hours spent in the car a year (presuming you took four weeks vacation), or 14,400 hours until you are 65.

If you jog six miles twice a week, you’ll jog 46,800 miles, which is just shy of two laps around the world.

If you watch two hours of TV every day, that’s 54,750 hours of your life spent on the couch. And how many of those episodes were reruns?

If you write one page of a novel a day, five days a week, you’ll have written 65 books of about 300 pages each before you die. Of Mice and Men is only 112 pages.

If you practice guitar 30 minutes a day, five days a week, you’ll practice 130 hours a year. If you believe what Malcolm Gladwell writes in Outliers: The Story of Success, you’ll gain the requisite 10,000 hours of experience required to become a phenom in 77 years. If you up that to 1 hour a day, six days a week, you’ll be phenomenal in 32 years.

Think about that as you go about your week. Stop thinking about your life in terms of what you did this week, and instead, imagine if each thing you did on any given Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday or Friday were multiplied across your entire lifetime. What if your body was like a player piano, and the next week of your life would be the week that would get recorded and replayed automatically for the rest of your existence? When they tally up all the time you spent in your life doing everyday things, what will the sum of your loop be?

With that in mind, I’d like to issue you a challenge: Take a look at your week and change one thing about it. Just one thing, that’s all. Whether it’s the eradication of a bad habit or the cultivation of a good habit, I want you to give it a try. I think you’ll find it surprisingly challenging and rewarding.

Let me explain further.

Part II: Breaking the Habit Loop

If your year is made out of week-long loops, then what are your weeks made out of? As it turns out, more loops. These loops can span over an entire day, or they can be as short as a five minute routine. But the majority of what we do throughout the day is, on some scale, a habitual routine. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing. We humans are hardwired to develop habits. They allow us to perform certain everyday tasks, such as driving, brushing our teeth and breathing without thinking about what we are doing.

At the lowest level, habits allow us to literally walk and chew gum. Imagine trying to concentrate on a lecture or read a book if you had to constantly will yourself to inhale and exhale at a steady rate. But on a broader scale, habits allow us to get up, go to work, do our chores and meet our worldly obligations without reinventing the wheel each time. Of course, there are some people who carefully weigh the pros and cons of getting out of bed each morning. There are people who have to expend a vast amount of mental and emotional energy just to do basic things like wash their hair, leave the house and see people face-to-face. We usually call them depressed people.

What I’m trying to say is that it’s normal and healthy to have habitual routines. Habits make life livable, rather than an endless string of tough decisions. But habits are a double-edged sword. Habits, as you know, can be good, neutral or bad. Sometimes it depends on how well the habits are moderated. But the thing that most habits have in common is that we don’t form them consciously. They grow on us like mildew on leftover rice.

How Habits Form

As author Charles Duhigg explains in his book The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do In Life and Business, habits are self-reinforcing loops that consist of a three-part psychological process: (1) the trigger (2) the routine behavior and (3) the reward. Essentially, your brain learns to associate a certain reward with a routine behavior.

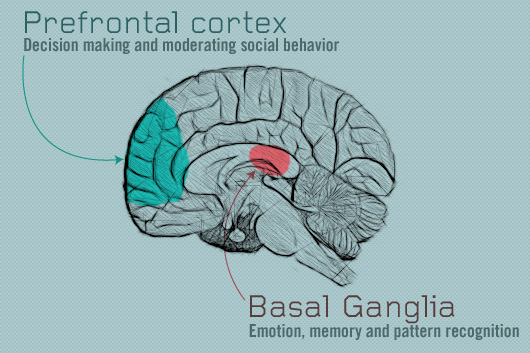

In order to recreate that reward—say, a shot of endorphins, a sugary boost or momentary relief from a stressor—your brain will trigger that routine behavior in certain situations. At first, the behavior might be something conscious or coincidental. You make up your mind to do something and you do it. But once your brain picks up on the reward that results from the behavior, a funny thing happens. The impetus to start the routine behavior moves away from the decision-making part of your brain—the prefrontal cortex—and instead starts coming from your basal ganglia, the part of your brain that’s involved with emotion, memory and pattern recognition.

As the habit starts getting more deeply ingrained in your basal ganglia—the pattern recognizing, memory and feeling part of the brain—the prefrontal cortex’s role becomes smaller and smaller.

It’s sort of like your brain is a hybrid engine. When the electric motor is cruising along, the combustion engine can shut off, saving you gas. And, as explained above, that’s the benefit of habits. They let us save our brainpower for the big decisions, rather than agonizing over which shoe to put on first or when to cut the wheel when parallel parking.

Things start to go awry, though, when you want to change your habits. Habits are notoriously hard to break, even when you can think of a thousand logical reasons to do so. That’s because the decision is no longer up to the part of your brain that draws on logic and reason to spur action. Before you’ve even started trying to motivate yourself to do something different, your basal ganglia has already made up your mind.

This doesn’t mean that all hope is lost. It means that the key to breaking a habit is to rewire your brain.

I’ll present my own example.

Part III: How I Quit Smoking Without Even Trying

From the time I turned 18 till about the time I graduated from college, I smoked. I didn’t smoke very often—maybe three or four cigarettes a day. But I did smoke every day. I would typically get the urge to smoke when I was studying, or at crowded social gatherings, such as parties or concerts. When the urge to smoke cropped up, I’d leave the building and I’d go outside and have a smoke. The urge to smoke would be gone for the next four or five hours.

After about four years of smoking cigarettes, I pretty much resigned myself to being one of the many Americans who was addicted to nicotine. I had heard, after all, that nicotine was more addictive than heroin. Indeed, if I was in a situation where I was unable to leave to go for a smoke—an intense 2.5 hour honors proseminar, a 4 hour work shift, a boring movie—I would get physical sensations that I associated with cravings: an itch at the back of my throat, tenseness throughout my neck and temples. And when I finally did get a chance to smoke, they would cease. Sometimes it would take more than one cigarette, but the act of going out for a smoke would rebaseline my anxiety.

But something interesting happened to me and my smoking habit in my senior year. Over the summer, while volunteering for Habitat for Humanity, I met a girl. I liked this girl so much that I decided to date her. The only thing: she lived in Pittsburgh and I lived in Iowa. What that meant was a lot of plane rides over long weekends. I ended up spending about every other weekend in Pittsburgh. My routine during the week would stay the same, but whenever I saved up enough money, I’d hop on a plane and spend two or three days 800 miles away in a different timezone. And during those weekends in Pittsburgh, staying with my girlfriend, I wouldn’t smoke. I even brought a pack with me, but I’d very rarely smoke a cigarette, even if we were waiting outside at a bus stop or sitting at a bar or mingling at a wedding. One of the first things I’d do after getting back home to Iowa was light up a cigarette. But when I was in Pittsburgh, I hardly ever got the urge.

When I graduated, I moved to Pittsburgh permanently and subsequently quit smoking permanently. Even though my girlfriend was a non-smoker and wasn’t particularly fond of my smoking, she never asked me to quit smoking, nor did I ever make a conscious decision to stop smoking. The urge to smoke simply petered away.

What happened here?

Truthfully, I didn’t fully understand how I was able to kick my addiction to cigarettes until I began writing this piece. But if we take what Charles Duhigg learned from all those neurologists and psychologists and apply it to my story, it makes perfect sense.

Let’s start by mapping out the three parts of the habit loop. When I was smoking, I knew that I should probably quit. I had read the Surgeon General’s warnings on the packages. I had taken DARE class. But still, my habit was too strong to break. At the time, I assumed that the reward I was seeking was fulfillment of my body’s craving for nicotine. The habitual routine that netted me that reward was smoking cigarettes. And the trigger that set that habitual routine into motion was the craving for nicotine.

According to a basic understanding of chemical addiction, that all makes sense. But when you consider how I quit smoking, it doesn’t. Graduating college, moving to Pittsburgh and living with my girlfriend have nothing to do with my physical addiction to nicotine. Yet those are the things that ultimately broke my smoking habit.

What’s up with that?

As Charles Duhigg explained on Fresh Air, “The weird thing about rewards is we usually don't know what we're actually craving.”

It turns out that my urge to smoke had far less to do with chemical addiction to nicotine than I assumed. Instead, the reward that I was reaping was (in most cases) an escape from an awkward or overwhelming social experience. Whenever I was being hemmed in by strangers or judged by professors or stifled by crowds or homework, I would get the urge to smoke. But it wasn’t the cigarette that I was really after—it was the excuse to go outside, catch my breath (ironically), and feel comfortable for a few moments before diving back in.

In my case, I wasn’t addicted to nicotine—or at least not enough for it to be the primary reward for my smoking habit. That’s why I was able to quit smoking without nicotine patches or gum or any symptoms of withdrawal. The thing that helped me quit was a radical change in my routine. By graduating college and moving away, I essentially changed every aspect of my life, from where and when and how I woke up to what I did with my time throughout the day and how I got to the places where I was going. Because all my cues had changed, my habitual routines became vulnerable to change as well.

Duhigg explains this on Fresh Air: “If you want to quit smoking, you should stop smoking while you're on a vacation because all your old cues and all your old rewards aren't there anymore. And so you have this ability to form a new pattern and hopefully be able to carry it over into your life.”

That’s precisely what happened to me when I moved to Pittsburgh. All my old smoking friends were gone, so there was no one tempting me to step outside for a breather, a private moment to escape and feel comfortable. I also endured a brief period of unemployment after graduation, and so was subjected to virtually no long periods of time where I was held captive by a job or a class or a meeting. Proving the point further, I did briefly start smoking again when I started my first job after several months of being a non-smoker. My smoke breaks were an opportunity to commiserate with my fellow new hires about the harsh, unfamiliar territory we were all experiencing. Eventually, when that feeling of being overwhelmed and uncomfortable subsided, so too did my smoking habit.

Part IV: Breaking Your Habit Loop

That’s enough about me. There’s much from Duhigg’s explanation of habit forming that can be applied directly to habit breaking. If you are forming an action plan against a bad habit or for a good habit, do this:

Identify the reward

As Duhigg mentioned, the trickiest things about habits is that we often don’t recognize the reward that we are seeking. If I would’ve tried to quit smoking by chewing nicotine gum or wearing a nicotine patch, I probably would’ve failed. That’s because the thing I was after was an escape from an overwhelming situation, not a chemical fix.

This is the most important thing to understand about your habits if you want to break them. If you don’t find another way to get that reward, then changing your behavior is going to leave that void unfulfilled. Figuring out what makes you tick may require a new perspective, so don’t hesitate to talk it over with someone you trust or a professional therapist.

But first, try walking through your entire habit from start to finish. Quash your assumptions about your habit and ask yourself: What triggers your habits? What do you do specifically when you are acting on a habit? And what feelings result from those actions?

Identifying what it is that your basal ganglia is truly after can flip the light switch in a big way.

Take a vacation

If you don’t have enough paid time off saved up, then take a vacation from your routine. Wake up 15 minutes earlier, drive a different way to work, rearrange your apartment. Do something that shakes up the environment that your brain is hardwired to respond to automatically. Prime yourself for change and strike while the iron is hot.

The secret is to change something that you do in your routine that isn’t necessarily tied to a reward. Focus on meaningless autopilot actions, like tying your shoes, brushing your teeth or driving to work. These things are easy to disrupt because altering them won’t create an immediate void, and your mind or body won’t go into “withdrawal” from a routine reward.

Want some more ideas? Try some of these 10 ways to shake up your daily routine. I promise you, I am 100 percent serious about every one of these.

10 Ways to Shake Up Your Daily Routine

1. Shave your head. Wear contacts if you normally wear glasses or wear glasses if your normally wear contacts. Start calling yourself “The Rocket” and give everyone high fives and fist bumps. Even strangers and superiors at work. Especially strangers and superiors. Your new personality will grow on you.

2. Rearrange your bedroom. Sleep with your head on the opposite side of the bed. Keep your alarm clock at your feet and literally get out of the other side of your bed.

3. Wake up 30 minutes early. Leave for work 30 minutes early. On your way there, stop somewhere. Get a cup of coffee. Read a book. Or just sit on the street corner and watch people walk past. Do this every morning.

4. Stop eating meat. Or stop eating cheese. Or stop eating foods that are red. Make up an arbitrary rule in your diet and follow it for the sake of following it.

5. Do everything you would normally do in reverse. If you take a shower, brush your teeth and walk the dog every morning, try walking the dog, brushing your teeth and then taking a shower.

6. Get a dog.

7. If you go by a nick name, start going by your full name or vice versa. Start pronouncing your last name differently when talking on the phone to strangers.

8. Eat dinner for breakfast. Eat breakfast for dinner. Keep M&Ms in a pill bottle and pop them throughout the day. Pretend they are mood altering drugs.

9. Dump your girlfriend. Dump your friends. Get a new girlfriend. Get new friends. Better yet, don't dump anyone and just pretend you did. Start your relationships all over. Ask them all the questions you asked them on your first dates. You might be surprised by the answers.

10. Snap your phone in half and throw it off a bridge. Or trade it in at Amazon for cash, get a dumbphone and then buy 30 pounds of pistachios with the rest of the money.

Obviously, not all of these represent radical or even relevant changes in your life. But the idea is to get your brain receptive to change. Like derailing a train with a penny.

Believe you can change

This sounds a bit hokey, but this is one of the foundations of what has helped so many recover from debilitating addictions. I haven’t discussed it much in this article, but it is, in a way, addressed at length in another Primer article: Conquering the Enemy Within: Ignorance + Confidence = Success. To a certain degree, I exhibited some self-defeating behavior when I continued smoking in spite of knowing that I shouldn’t. I never attempted to quit because I assumed that I was addicted to nicotine, and therefore assumed the ordeal of quitting would be painful, frustrating and ultimately insurmountable. When I moved to Pittsburgh, I sort of half-joked/half-believed that my girlfriend was my “anti-drug.” I adopted the mindset that when I was in Pittsburgh with my girlfriend, I didn’t need to smoke. I was completely ignorant of any logic behind that reasoning. And in a strange roundabout way, it became true.

This point isn’t about magical thinking. It’s about recognizing self-defeating thoughts and allowing logical thoughts room to breathe. By doing this, you’ll find it worthwhile to give breaking a habit a try.

Conclusion

If you want to change your life, the first thing you have to do is change your habits. The totality of your existence is composed of the tiny decisions you make from moment to moment, from week to week, year in and year out. Habits put those decisions on auto-pilot, which means that your conscious will is no longer in the cockpit. The key to changing your habits is to trace that automatic response back to its source: the rewarding feeling you get when you perform a habitual routine. Identifying that is tricky, but once you do, you can work on disarming the trigger that sets the habit in motion, changing the routine that nets the reward, or replacing the reward itself with something healthier and more fulfilling. Once you’ve gained the ability to shape your habits, you’ve gained the ability to direct your life in a more meaningful direction.

Good luck.