Everybody has that moment when they realize they don’t know about something that they should probably know about. Whether it’s history, language, science, or cultural phenomena, you’ve felt the stinging personal embarrassment of a moment wherein you realize there’s some common knowledge that isn’t so common. Don’t feel bad; nobody knows everything. Nobody, that is, except me and my sidekick, The Internet!

This week…

Everything You Didn’t Know About Halloween

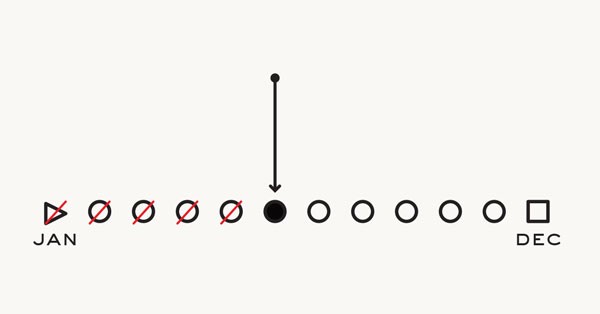

Even though Halloween is one of the most popular holidays in America, it seems like – beyond the name “All Hallows Eve” – the intricacies of its origin story have been completely ignored by most people, especially when compared to holidays like Christmas or Thanksgiving.

So from where did this October tradition originate? What was its initial purpose? Are there any real religious themes involved? What’s the deal with all the emphasis on scary figures like ghosts and witches? When did the handing-out-candy routine start? Who conceived the Jack-o-Lantern? Do any other countries celebrate it in a fashion comparable to America? Put on your cape and grab your Jack-O-Lantern candy bucket and let’s go find some answers.

Essentially, the holiday we now know as Halloween began as a Celtic celebration called “Samhain” (pronounced ‘sow-win’) that was regarded as a combination of Celtic New Year’s Eve where they honored end of the summer/the beginning of “the darker half” of the year (an allusion to the shorter days of Fall and Winter) and a “festival of the dead,” which grew out of the fact that the changing of the seasons apparently reduced the distance between Earth and the Otherworld.

From there, the accounts of Samhain customs tend to get really familiar. Families would celebrate this Romero-less day of the dead by simultaneously welcoming the spirits of deceased ancestors and warding off evil, unwanted spirits. In order to protect themselves and their home from the latter, people took several actions:

- placing a symbol of the dead in a window or in front of the house — usually a skeleton or skull carved from a vegetable like a turnip or rutabaga

- wearing masks and/or some sort of costume to frighten away any spirits they may encounter outside of the home

- extinguishing most lights in and around the house, to make their homes cold and unattractive to roaming evil spirits

In other areas of the old world (generally before Roman conquests in Celtic territory), young men would impersonate the evil spirits as part of a belief that the day was to be wrought with mischief – they would aim to confuse by relocating the farm equipment and livestock while also hurling heads of cabbage at the homes of ungenerous citizens. Many communities would ignite large bonfires and gather around them, wearing animal heads and skins as symbolic costumes, to burn crops and animals in sacrificial fashion to please the Celtic deities. Both the Celtic priests and townsfolk would try to tell each other’s fortunes, as they believed the presence of spirits (good and bad) on October 31 aided one’s ability to predict what the coming winter would bring.

All of these ideas still have obvious root in the modern Halloween:

- We still welcome “spirits” of friends and family to our door (though we all really got tired of being ghosts for Halloween around 1941 and started to go more in the direction of “awesome movie characters” when it came to costumes).

- While we all may not believe that evil spirits roam the Earth on the day before All Saints’ Day, most of us do tend to dim the lights and adorn our homes/front lawns with terrifying accoutrements, including faces-carved-into-vegetables (in North America, the larger and more readily-available pumpkin quickly usurped the turnip).

- Pranks carried out by young people are still extremely prevalent on Halloween, except toilet paper replaced cabbage at some point along the way (probably for the best).

- Telling generally spooky stories about the perils of the future that may or may not involve ghosts and death is a tradition no longer limited to taking place around a fire only on Halloween but its roots (replete with costumes) obviously began with Samhain.

The idea of going door to door for some sort of reward has root in the Middle Ages, where people of any age would go door-to-door on All Saints’ Day (November 1) and ask for food in return for prayers they would make on All Souls’ Day (November 2). While this tradition was common in many parts of Europe for years, what we now know as “trick or treating” did not seem to take shape as part of American Halloween revelry until the early 20th century.

The term “Jack-O-Lantern” apparently comes from an Irish legend about a man named Stingy Jack, who was a slimy, double-crossing, no-good swindler (like Han Solo but with a drinking problem instead of a spaceship). The Devil heard about Jack and his actions and wanted to verify the man’s reputation in person. Long story short, Jack lived up to the hype and tricked the devil twice over the course of ten years, resulting in a deal that ensured the Devil would never be able to take Jack’s soul to Hell. Unfortunately, when Jack eventually died, Heaven understandably did not want anything to do with the man and the Devil was still bound by his own deal and thus, could not allow Jack to pass through the Gates of Hades. Doomed to roam between the two worlds forever, the Devil offered Jack only an eternally burning ember to light the never-ending journey. Jack apparently put the ember inside a hollowed-out turnip at some point in his infinite boredom and boom, Jack-o-Lantern. It should be pointed out that because this story involves people like God and the Devil, nobody’s too sure of its true accuracy.

With their rich Celtic history, Halloween (and the entire month preceding it, in fact) remains a significant time of celebration in Ireland and Scotland. Neighboring England and Wales also observe the holiday in varied fashions. Additional European nations like Germany and the Netherlands began taking part in Halloween-related festivities just in the last 20 years or so. Many other countries around the world celebrate the day though very few of them associate it with any part of its Celtic history; nations like Mexico (as well as many other Central and South American countries), Australia, and Japan only began to observe the day once American and European popular culture gained more global visibility.

Oh, and where did “All Hallows Eve” come from, you ask? All Saints’ Day (November 1) is also known as “All Hallows” and so, the day that falls before All Hallows would gain notoriety as being “All Hallows Eve.”

Now you know.