Chug, chug, SQUEAL! Hear that? Chugga sliiide. That's the sound of Metal Tuesday – the day of the week when all Electric Owl Studios employees are required to rock out to heavy metal for the entire day. Stuff like this isn't exactly standard operating procedure in a typical office – but it is for the next generation of start-ups and young entrepreneurial firms. How does anyone get any work done in an environment like this? Well, it takes a special breed.

“If you can't handle a Nerf rocket flying at your head when you are trying to code…” says Fred Gallart, CEO of Electric Owl. “…then you might not be a good fit.”

I won't say that it's not all fun and games at Electric Owl – after all, they do design video games – but that certainly doesn't mean that nobody's taking care of business. In just two short years, Electric Owl Studios has raised funding from Idea Foundry, bagged a tidy contract from the Childrens' Hospital of Pittsburgh and, in a way, helped the Pens win the Stanley Cup.

While Electric Owl has its own unique personality and niche market – they create high-tech toys to keep kids entertained in waiting rooms, called the Kids Interaction Creation Kiosk (K.I.C.K., partially inspired by fellow Pittsburgher, the late Fred Rogers) – Electric Owl's style is notably representative of the changing skill sets needed to be a successful entrepreneur in the digital age – characteristics that are, in some ways, starkly contrasted to the go-getters of yore but in other ways, just the same. A DIY-attitude, resilience in the face of risk (and failure) and adaptability – especially adaptability – are still as important as they ever were. Stuff like donning a three piece suit, organizing high octane power lunches and nabbing an Ivy League MBA – less so.

Take a look at the education background of the team at Electric Owl Studios – they have three masters of entertainment technology from Carnegie Mellon University, a couple bachelor of science degrees and some bachelors of fine arts. Conspicuously absent from this list: MBAs, business school alumni and management majors. Which, if you think about it, isn't particularly peculiar. In this age of innovation, qualities like creativity and collaboration are far more valuable assets than the ability to read a balance sheet and tactfully layoff an employee. For the folks at Electric Owl, that very creative spark was fanned into a flame at CMU's Entertainment Technology Center (tagline: “The graduate program for the left and right brain…”) and carried over to their offices in East Liberty, Pittsburgh.

“CMU is different from many schools in that they encourage interdisciplinary study rather than setting up barriers to prevent it,” says Gallart. “The ETC itself is a very unique animal in that it is a ‘melting pot' of people from backgrounds ranging from music to psychology to computer science. When you have access to such a broad range of talented people, the chances that dynamic teams can form dramatically increase.”

In the office, Electric Owl continues to favor the melting pot layout over the cubicle catacomb. In fact, the mezzanine level of 6101 Penn Avenue is home to both Electric Owl Studios and another ETC venture, Interbots. Like the ETC program, the workspace is notably barrier-free. It's an open floor plan loft in a renovated bank building – a no wall productions property – which provides apt opportunities for ideas and innovation to spill over.

“You have this amazing collaboration between two entirely different companies/teams. It allows for very open communication, and keeps everybody very honest,” says Gallart. “Everybody's personality is on display.”

Coincidentally, on the sixth floor of the very same building is another CMU spinoff: Deeplocal. Deeplocal is a “software design, development, and strategy studio” that brings together “artists, designers, and technologists to solve complex communication problems with a focus on usability and simplicity.” Like Electric Owl, the curriculum vitaes at Deeplocal are markedly free of

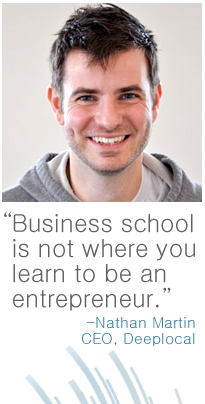

“I don’t believe in teaching skills,” he says. “I believe that great people will teach themselves what they need to know and school is about fanning passions and allowing great minds to explore and experiment.”

Martin first attended art school at age 16 and now holds two fine arts degrees – a BFA and an MFA. And he is nearly evangelical about the virile merits of studying the arts – even for those who want to start their own business.

“Business school is not where you learn to be an entrepreneur,” Martin says. “I think that, right now, university arts programs are the one institutional place where people seeking to become entrepreneurs can learn the most necessary skills to being an entrepreneur.”

Essentially, Martin seems to be saying, the driving force behind a successful business isn't technical knowledge or business savvy – it's passion, something that's difficult to teach. Coaxing out your true passion is a matter of exploration, not regimentation. “I think that everyone should just take courses they think sound interesting. Ignore grades and degrees as much as possible,” Martin says before adding a call to action: “Take more art classes and fund the arts!”

The values of an inquisitive, artistic mind comprise Martin's idea of an ideal employee, too. “I go with my gut when making hiring decisions,” he says. “We look for employees that code for fun, are competitive enough that they want to be great, are driven enough to require nearly no oversight, and are creative enough to understand the value of the arts. Beyond all of that, they have to have good social skills and possess a passion to learn more. They have to understand that they don’t know everything – none of us do. It seems easy, but it is very hard to find. Deeplocal is made up of some of the most amazing people I have ever worked with and I enjoy coming to see them every day.”

With such a small team, fitting into the culture is exponentially more important than it would be at an inside-the-box office. Deeplocal hires rarely, but when they do, they look for “rock stars.” In their job posting for an intern this fall, they note that there's no dress code: “we only ask that you wear clothes; preferably not pajamas.” They also say that it's “important to note that we have a foosball table, mini-basketball hoop, and team yoga…not to mention an affinity for playground sports (our kickball team is pretty awesome.)” (They’re not kidding about the kickball – they recently created Pickupalooza to help facilitate pick-up games with friends and strangers. It’s kind of like Match.com meets Twitter meets gym class.)

The foosball table, though, shouldn't be mistaken as a sign of sloth or distraction – rather, it's more of a representation of the attitude at Deeplocal: smart, creative people doing work that they enjoy. The foosball table actually “collects dust,” admits Martin. Mostly because the employees are hardly ever burnt out or bored – they're too busy. When asked about the relatively “laid-back” environment of his office, Martin protested.

“I doubt anyone would describe me with that phrase, and Deeplocal really reflects that. We are comfortable with one another and try to keep Deeplocal work from invading our personal lives, but we don’t really have a laid-back atmosphere,” Martin explains. “We have mutual trust and know that we are all working for the same goal of having a great company, and we want to be great in the world, not just in Pittsburgh. We want to keep building on our wins and staying excited about life. While we aren’t as rigid with time schedules as some companies are, the reality is that when we are at work, we love it, and our days fly by.”

The metamorphosis from artist to CEO may seem a little surprising to most people – Gallart and Martin included. “It has been a wild and radical transition for me,” says Electric Owl’s Gallart, “I came from a fine arts background, and now I am leading a company.”

When asked how he gleaned the skills and expertise needed for running a business, Gallart admitted, “Honestly, I’m still ‘learning the ropes.’ You will likely get that answer from any entrepreneur you ask. New things come up every day that you never even thought of.” Gallart quoted an apt metaphor for the process of maintaining an upstart: it’s like nailing down warped boards – as soon as you get one side nailed down, the other pops up behind your back.

But Gallart’s roots in interdisciplinary collaboration and adaptation have helped him tackle the unexpected and survive. Thanks to CMU’s own no walls policy, Gallart was able to enroll in some “mini classes” at its Tepper School of Business where he met his mentor, Dr. Tom Emerson, the director of the Donald H. Jones Center for Entrepreneurship. In Dr. Emerson’s recent paper, co-authored with Arthur Boni, he claims that entrepreneurship education “should extend beyond the walls of the business school” and reach out to graduate students and faculty in other schools in the university.

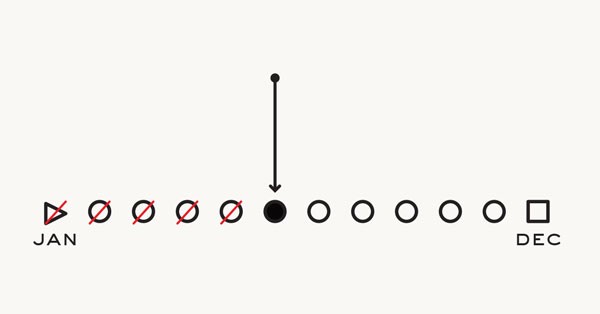

In the case of Electric Owl Studios, the impetus of the company has clearly been the creative spark. But the sustenance of the venture has a lot to do with adaptability and rolling with the punches thrown by a kicking and screaming marketplace. While Electric Owl Studios’ flagship product remains the K.I.C.K., which will be rolling out in 30 hospitals nationwide this summer, Gallart and his team aren’t adverse to hedging their bets.

“We are a kind of two-headed organism in that we both offer a product and take on contract work,” says Gallart. “We are often urged to pick a direction and go with it, but both aspects of the business are doing their jobs relatively well in terms of keeping us alive. We like to keep it interesting here, and the variety of work we have turned out speaks to that point.”

Indeed, the irons in the fire at Electric Owl Studios, like its team members, span many interests and disciplines: Extra Attacker, a fantasy hockey game developed for the Pittsburgh Penguins; Splash! an interactive digital art community developed for the ArtThread Foundation; and an unannounced project with Interbots, their studio-mates who develop “compelling interactive characters” (i.e. real live robots).

Gallart’s neighbors upstairs have also weathered several changes of courses in order to stay alive. Deeplocal began as a collaborative mapping project called MapHub. Like Gallart, Martin found taking the plunge from art to business a bit jarring at first. He says, “Many of the skills I had developed were highly useful but the logistics of running a business required me to learn a great deal and very quickly. The biggest challenge was after our first year spent attempting to commercialize MapHub. I had to accept that we were not winning the battle and that my advisors were all giving me different directions.”

After MapHub stumbled, Deeplocal regrouped and went back to its roots: “making cool use of both old and new technology.” Before launching his business, Martin spent the better part of a decade running an art group called Carbon Dense League. The CDL, described as an “artist collective” that hacked and pranked its way into the social consciousness, was responsible for such stunts as re-code.com, which stuck it to Wal-Mart (and almost got Martin tossed in the slammer) and FTheVote.com, which enlisted the wiles of “sexy liberals” in order to sway the votes of some of the more stodgy, sex-starved Republicans. Both moves were highly controversial and gained attention on a nearly viral magnitude.

Still, in spite of Martin’s radical roots, he now employs a more traditional model of gaining awareness of his brand. Whereas some tech-oriented ventures rely on social media to spread the word, Martin’s strategy is a bit more fundamental: “What matters first is to do awesome work. What matters second is for our audience to know about that awesome work. That will forever hold true for almost any company. While the speed of awareness can happen much more quickly with the adoption of large-scale social networking tools such as Twitter and Facebook, you still have to make great shit that works.”

Some of Deeplocal’s own “great shit that works” includes RouteShout, which lets commuters track bus routes by text message, CallBits, a sort of smart switchboard for customer calls, and Flrti, which allows anonymous flirting with nearby strangers. Web and mobile services like these that extend into the real world are markedly different from the unsustainable, high-risk, low profit ventures of the first tech boom. And that’s how Martin likes it.

“I really believe the future is in services that truly benefit a user’s lives and ideally have some real-world connection,” he says. “It’s the Luddite punk rocker inside of me that wants to see real world impact from web-based software.”

Martin calls the adoption of mobile information a “no-brainer.” He says, “What is happening across all devices is the evolution of information access. People are expecting efficiency – not just access. This places the burden on designers to be incredibly smart about how and when to deliver appropriate information. The smaller form factors have always excited me as well because they demand simple and intuitive design. I think mobile is clearly surpassing antiquated devices such as televisions because they travel with us. For better or worse, we are always tethered to our mobile devices.”

That, perhaps, hints at the keynote of the stories of Martin and Gallart: the heart of a successful business is innovation and adaptation. In other words, invention. The social and economic environment of the modern age is exploding in all directions. In fact, in just a few short decades an entire other plane of existence has emerged from the vast amorphous, fractal-like network of intersecting technologies. Such radical change in landscape demands leadership that is equal parts inventive, obsessive, nimble and playful – a balancing act which is more of an art form than a business model.