Jeff Barnett is a fitness enthusiast from Huntsville, Alabama. For the past ten years he has pursued strength and health in numerous ways including serving as a Marine Corps officer. He posts his daily workouts on his website, CrossFit Impulse.

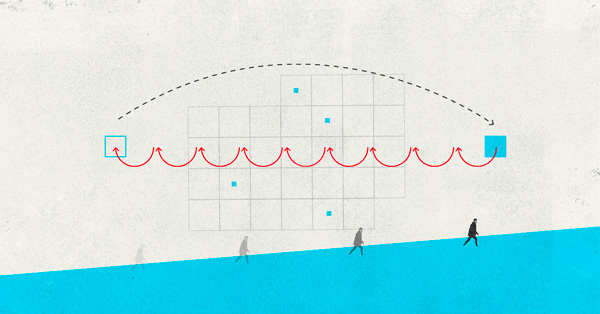

Overtraining is a mysterious and delicate topic, yet most of us have experienced it in some form. Rigorous training without overtraining is extremely difficult to achieve. You’re trying to intentionally and frequently cause short-term damage to your muscles without causing any long-term damage. What a balancing act!

The balancing act is even tougher when viewed as a cost/benefit relationship. Train and you’ll improve. Train rigorously and you’ll improve even more. Train too rigorously and not only will you not improve (you’ll injure yourself), but you will lose your ability to fully train while the injury heals, causing you a net decrease in performance.

Injuries due to overtraining usually result from one of two things: a single catastrophic event or chronic overuse. Here are some ways that I personally mitigate these injuries.

Try It Before You Buy It

When trying new exercises for the first time, which is something you should do often, never go full speed or with a full load your first time. This is something we all “know” but I’m not sure how religiously we practice it. Practice the motion unweighted for a few reps. Try to anticipate where you will feel the most stress and pay attention to those joints/muscles during the actual exercise. If the exercise involves a barbell then do a few reps with only the bar until you’re confident with the motion. This is especially important with complex motions like the clean. It’s OK to fool around with just the bar before you dive in head first. You don’t have to count the reps toward your workout, and you’ll benefit in the long-term.

Know Whether You Are Hurt or Injured

More specifically, know the difference as it is happening. At The Basic School in Quantico, Virginia, I once saw a captain approach one of my fellow lieutenants who was rubbing his lower leg during a break in physical training. “Are you hurt or injured?” he asked. “If you’re injured then stop and go see the doc. If you’re hurt then suck it up and let’s go.” Pain is a normal part of exercise. You should expect and even seek a certain amount of pain in your training in order to improve. However, you must be able to tell when pain is giving way to injury, and sometimes it changes in an instant. My perception of the normal muscular stress of exercise: widespread burning, tightness, soreness to the touch. The onset of injury is more acute: sharp “cutting” pain, intense cramping, immediate and severe loss of strength. When an injury is about to occur you will feel the normal pain transition to injury. Sometimes it happens so quickly you can’t prevent it during the moment. In that case you were simply doing too much too soon. However, sometimes you can feel it happening and stop it in time. Building this perception and being willing to preserve yourself can save you from some injuries.

Take a Spill in Front of Everyone

…or at least be willing to. When you feel a catastrophic injury approaching you must unload the muscle to prevent it. You essentially have two options: shift the load to a different muscle group, sometimes one that the exercise position can’t easily support, or dump the weight. Make preparations in advance and be willing to dump the weight if you need to. Admittedly, I rarely do this. A corollary to this tenet is to anticipate your performance on future sets/reps and adjust load/reps accordingly before you start. Rubber bumper plates are excellent for exercises that involve large loads and high probability of failure if pushed to the limit. A spotter can also mitigate this risk. However, if all else fails and your knee/shoulder/insert important body part here is on the line, be willing to create a scene and suddenly let the weights clang to the floor. Your embarrassment will buy you out of a lot of pain and frustration.

Give Yourself a Break

I’ve given a lot of attention to catastrophic injury thus far, but overuse has plagued me far more often. A fitness enthusiast learns and eventually expects to work through pain. This is both a virtue and a vice, because it’s this ability that causes us to substantiate working through injuring pain. This most often happens in endurance training such as running. In 2003 I developed shin splints so badly that a month of rest was necessary to regain my long-term running ability. The fact that I was limping into the gym should have been a clue that all was not well. Because the pain went away after my first 1000m I was determined to work through it. That was a mistake. Whenever any soreness doesn’t subside after 4-5 days then you have reason for caution. You don’t always have to wait until every muscle in a group has healed completely to work the muscle again, but if the muscle hasn’t felt fully healed in weeks then you’ve got a problem. Unfortunately, there’s only one cure: rest. Resting a week at the onset of injury is preferable to resting a month after greatly aggravating the injury. If you’ve been training for months then a week or even two weeks of rest isn’t going to hinder your long-term goals.

Crying Wolf or Pleading for Help?

I hope that some of the tips can help you avoid overtraining and the injuries it brings. The advice I’ve written is the advice that I give myself every day and seek to follow in my training. The sum of all the parts is this: know your body and listen to it, but listen to it as a concerned parent — not a whimsical friend. In order to effectively train and develop total fitness you must push your body outside its comfort zone. It’s always going to be a little upset about this, and you often must tell it to shut up and keep moving. However, from time to time it will genuinely cry out for help, and in order to effectively respond you must know how to tell the difference and be willing to listen.

![It’s Time to Begin Again: 3 Uncomfortable Frameworks That Will Make Your New Year More Meaningful [Audio Essay + Article]](https://www.primermagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/begin_again_feature.jpg)