Tell me if this sounds familiar:

You check the news in the morning and almost immediately feel your heart rate climb as you scan alarming headlines. You try to focus on work or school but you’re distractible, and it’s hard to think. Your stomach is sour. Your partner or roommate checks in with you and you’re irritable and weirdly sensitive. You check the news again and think, “Everything is so out of control. What’s going to happen?” Now your chest feels tight. It’s a little hard to breathe. You begin to ask yourself a terrible question:

“What’s going on with me? Do I have it?”

Pause.

Take a deep breath.

Recognize that everything is OK.

You’ve just stepped into the shoes of someone who’s anxious – and struggling to cope during COVID-19.

Does this scenario remind you of someone you’re close to, or living with? Does it remind you of yourself? If the answer is “yes,” you’re in the right place.

These Are Anxious Times

In a recent poll by the Kaiser Family Foundation, 45% of all adults in the US said their mental health has taken a hit due to coronavirus-related worry and stress.

Can you blame them?

Social isolation, vulnerable loved ones, record unemployment, medical shortages, and even a lack of toilet paper at the store are all real, concrete reasons to worry. And that doesn’t even include actually getting the virus yourself!

Anxious People Are Having A Hard Time

We’re living through unprecedented stress and it’s going to affect people who already suffer from anxiety even more. Take it from someone who copes with anxiety and knows what it’s like to have a COVID-related panic attack: me. It’s bad.

The good news is, there’s lots you can do to help yourself or an anxious family member or friend.

We Want To Help You Help Your Anxious Loved Ones

Primer is committed to helping people live their best lives whether it means managing your mental health or helping someone you care about during a time of crisis.

Also, being pretty anxious ourselves inspired us to create this far-from-exhaustive guide to help non-anxious people understand and care for their more-anxious family and friends.

It’s not meant to replace professional help, and if you or someone you know is experiencing anxiety that’s having an impact on their health or safety contact your doctor, or find the right helpline from the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

How To Help Someone With Anxiety

Understand What Anxiety Is

A neuroscientist I’ve studied with called anxiety “the union of worry and stress.” It’s an apt definition because it speaks to the anxiety’s two ingredients.

Worry is a mental or emotional concern about something. It happens in the higher order areas of your brain. It’s complex and intellectual.

Stress speaks to the neurological and hormonal impact of stressors on your brain and body. Stress disrupts homeostasis, and your response happens deep in the more primordial parts of your brain and endocrine system. It’s instinctive and automatic.

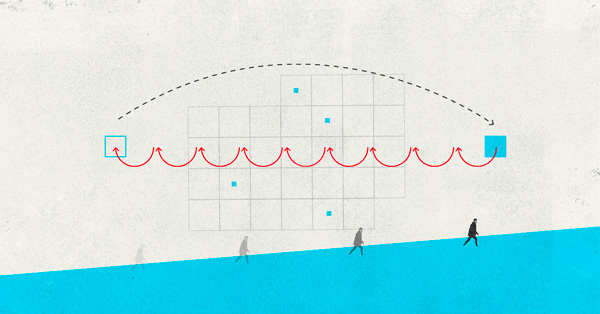

For non-anxious people it’s important to recognize that the runaway quality of anxiety doesn’t just happen in someone’s head. Mental worry triggers physiological stress, which then feeds more worry. Anxiety can be a powerful, self-feeding cycle.

Recognize When Someone Is Anxious

Googling a list of symptoms is dangerous. It’s all too easy to way over-diagnose what’s happening, which leads to more harm than good.

That said, it’s important to identify when someone is experiencing anxiety because it’s the first step in getting help. The scenario at the beginning contained a lot of the signs and symptoms of acute anxiety: feeling nervous, restless, or tense; having a sense of imminent danger; elevated breathing or pulse; trouble concentrating; difficulty breathing.

The point isn’t to try to play doctor, but it is to be observant and sensitive to how someone is feeling.

If your concern is more serious, it’s OK to pick a moment when they’re not stressed out and ask them if the standard anxiety symptoms reflect their life right now (this one from the Mayo Clinic is handy). If it rings true for them, it’s possible they may be experiencing anxiety that needs medical or counseling support.

Withhold Judgement

To paraphrase comedian Maria Bamford, whose work keenly (and hilariously) deals with mental illness: anxiety isn’t the flu. You can’t just ask someone to take some Tylenol and sleep it off.

It’s also not their fault (remember the hard-wired stress part of anxiety?)

Even if you find the object of someone’s anxiety to be trivial, it’s important not to judge them. They’re suffering, and you want to help.

Listen & Ask Open-Ended Questions

Simply listening is a huge part of helping someone with anxiety. In my experience, talking about what’s making me anxious serves two purposes: first, it releases some of the pent-up energy of my worry and concern. Second, saying it out loud to another person often helps me see that what I’m worried about may not be totally based in reality (more on that later).

As a listener, it’s helpful to ask open-ended questions like, “How are you feeling about that?” and “What would make you feel better?” rather than offering solutions.

Don’t Minimize Their Fears

You know what’s the least calming phrase in the world? “Calm Down.”

Dismissing, minimizing, or explaining away an anxious person’s fears will probably cause them to withdraw or get angry. Either way, it’s not constructive.

Give A Gentle Reality Check

As you try to support someone with anxiety, it’s OK to offer a non-anxious perspective after you’ve been a good listener.

Take this example: My daughter was scheduled to get a round of shots in April. COVID-19 was surging in our town. I was really stressed about the idea of my kid going to a doctor’s office – I kept imagining all the little virus particles from asymptomatic kids settling on the exam tables … waiting.

My wife (a non-anxious person) called the pediatrician’s office and asked if it was OK to come in. They explained their cleaning protocol and scheduled her for first thing in the morning to help avoid other patients. My wife explained this to me and said, “In this case, I think the risk of not getting her shots is greater than the risk of getting COVID.”

That gentle, well-informed reality check was what I needed to check my anxiety and move forward.

Seek Expert Help

Chances are, you’re not a trained therapist. And even if you are, you don’t necessarily want to be treating your spouse or uncle or roommate.

If your gut is telling you, “this is too much for me to handle,” you’re probably right and it’s OK to help your person get expert help.

I’ve been meeting with my counselor via Zoom for weeks now and having her support during this crisis has been invaluable.

How To Help Yourself If You’re Helping An Anxious Person

Your anxious partner, friend, or roommate isn’t the only one you should be thinking about. Avoid burnout, resentment, and a serious rift with these tips on self-care.

It’s Ok To Set Boundaries

One of the most difficult things about having anxiety is not being able to shut it off. Our brains evolved to detect danger, and when those circuits get over-activated it can snowball, making everything seem risky, dangerous, or triggering.

As a friend, spouse, or caregiver it’s your responsibility to take care of yourself, too. If your person is anxious about coronavirus, institute a “no COVID updates after 5 PM” rule. Make sure you’re getting time away from the pressure cooker environment that anxiety creates. Take time to get outside and be spacious, literally and mentally.

It’s necessary to create reasonable boundaries when someone is in crisis. Remember the old rule: a drowning person will climb over you to get to air – help them and yourself by not letting that happen.

Develop A Shared Language

What does “anxious” mean to you? How about your person?

Everyone feels different feelings and describes them differently, too. For instance, when my wife and I first started dating, I said I was “anxious” about a lot of things because in my family that word didn’t carry much weight. It was like saying, “I’m thinking about something in a slightly negative way.” To her, anxious meant something closer to “I’m really upset.”

It may seem like a small thing, but defining some key words will help you better understand what your person is feeling and when they’re really in crisis, as opposed to blowing off steam.

Get Your Own Support

If you’re the person your anxious partner talks to … who do you talk to?

Even if you’re not the one experiencing an episode of clinical anxiety, chances are you’ve got your own COVID-related worries, frets, and frustrations. Don’t hold it in until it blows up, or impacts your relationship.

Talking to friends, parents, mentors, or a professional counselor will help you process what’s happening, discharge any negative energy related to caring for an anxious person, and give you strategies for how to care for them (and you) better.

Also consider checking out Headspace, a guided meditation app that helps you relax, turn down the volume on your thoughts, and sleep better. It’s being offered free during the COVID crisis.

You’ll Get Through This And So Will They

If you were alive and aware of what was happening during 9/11 then you probably remember the feeling of profound instability during the days and weeks that followed. It feels to me like we’re in one of those times, except that COVID is a slower burn.

As an anxious person, I’m reminding myself that we’ll get through this – as a family, a community, a country.

A trick my old therapist taught me: ask yourself, “Am I OK right now?” For a lot of people, the answer is no, and that’s scary. But for a lot of people, the answer is yes. Focus on that “yes.”

Part of caring about an anxious person is trusting them to work it out. Chances are, it’ll happen – they’ll work it out, just like we all will in time.

![It’s Time to Begin Again: 3 Uncomfortable Frameworks That Will Make Your New Year More Meaningful [Audio Essay + Article]](https://www.primermagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/begin_again_feature.jpg)