You're on your couch watching television when you hear a knock at the door. You're not expecting anyone. You didn't order any takeout. Your girlfriend is out of town. As you approach the front door, still wondering who is there, a male voice booms out: “Good evening, it's the police. We'd like to talk. Would you mind opening the door?”

The scenario above elicits a host of questions. Do I have to answer the door? Do I have to speak to the police? Do I have to let the police in my home? Will the mountain of cocaine on the coffee table be a problem?

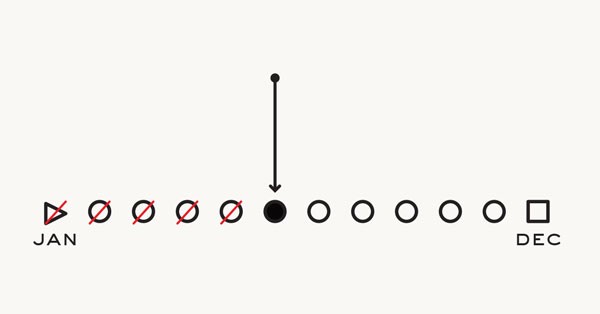

This article addresses a situation in which the police arrive at your home, knock on the front door, and ask to speak with you, an investigative technique known as a “knock and talk.” A knock and talk has two primary benchmarks: the interaction must be voluntary and consensual. If a knock and talk becomes involuntary or nonconsensual, it is no longer a knock and talk. Instead, it is some other situation, which undoubtedly creates a host of other constitutional concerns.

Let's be clear about the scope of this article. First, this article is not about the police arriving at your home with a search warrant. Houston-based criminal defense attorney Grant Scheiner has an excellent article addressing what to do when the police show up at your house with a search warrant.i In short, if the police have a search warrant, they have a right to enter your home and search the places described in the warrant.

Second, this article is not about the police arriving at your front door and demanding to be let inside. If the police demand that you act in a certain manner, your response is neither voluntary nor consensual; therefore, the resulting exchange is not a knock and talk.

Let’s take a look at the law surrounding the knock and talk procedure and your options in such a situation.

What the Law Provides

The Fourth Amendment of the United States Constitution states: “The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause.”ii In general, police must obtain a search warrant before conducting a search of a home or residence. However, federal law does not require police to obtain a search warrant to conduct a knock and talk.

To conduct a knock and talk, police arrive at a home, knock on the door, and ask questions in an effort to gain consent to search the premises. Federal courts have upheld the knock and talk technique as a constitutional method of investigation. One of the most frequently cited excerpts on the constitutionality of the police approaching your front door comes from the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals:

[T]here is no rule of private or public conduct which makes it illegal per se, or a condemned invasion of the person's right of privacy, for anyone openly and peaceably, at high noon, to walk up the steps and knock on the front door of any man's “castle” with the honest intent of asking questions of the occupant thereof — whether the questioner be a pollster, a salesman, or an officer of the law.iii

However, federal courts have also emphasized that a knock and talk must be conducted within narrow parameters. Some courts, while upholding the knock and talk technique as constitutional, express outright disdain for the procedure. Consider this scathing review of the knock and talk technique from Circuit Judge Terence T. Evans:

The police had no warrant when they went to apartment 7. They were taking a shortcut in the hope that something good (from a drug-busting perspective) would turn up. A little more work would have given the police the probable cause they needed to secure a warrant, but they didn’t want to take the time to do something more. They wanted to go to apartment 7 and see what, if anything, was up… As I see it, the seeds of this bad search were sown when the police decided to use the “knock and talk” technique. And that process—which sounds more like a friendly visit to sell tickets to a police picnic than a perilous visit to a suspected drug hive—is fraught with danger, not to mention constitutional problems.iv

In short, courts have deemed the knock and talk procedure constitutional. However, just because police can come to your home and ask to speak with you doesn’t mean you have to invite them inside.

Can You Say No to the Police?

Let’s make something clear: if the police ask to come inside your home or ask to search your home without a valid search warrant, you can say no. Period.

There are several misconceptions about what must be done when the police ask to search your home or ask to search your vehicle. Often, this is because police request permission in a manner that isn’t technically improper, but that implies an improper threat. Consider the following:

POLICE: Can we search your home?

RESIDENT: No, I don’t think so.

POLICE: Well do you want to go to jail tonight?

Notice the stark difference between what the officer actually says and what the resident hears. The officer asks to search the home. After being told no, he asks if the resident wants to go to jail. However, the resident hears that if he does not consent to a search of his home then he will go to jail.

There are several other situations in which the police will say things like “you know this won’t look good for you” or “we will take your cooperation into consideration”. These situations almost always involve the police either explicitly or implicitly making improper threats, e.g., we will arrest you for no reason other than that you won’t let us do what we want, or impossible promises, e.g., we will talk to the prosecutor and make sure you aren’t charged for the eight pounds of marijuana in your closet.

POLICE: Can we search your home?

RESIDENT: No, I don’t think so.

POLICE: You know if you don’t let us search your home then we are just going to go get a warrant. If you let us search your home right now, it will be much easier for you.

What the officer means here is that it would be much easier for him if the resident simply consents to a search. Remember the words of Judge Evans, above: “A little more work would have given the police the probable cause they needed to secure a warrant, but they didn’t want to take the time to do something more.”v The police know that there are certain constitutional requirements that must be met in order to conduct a search. However, they also know that consent eliminates these requirements. Quite frankly, the police are seeking your consent to avoid doing their job. Don't help them.

The short of it? You can say no if the police ask you for something. In any situation where the police make you feel that they have you pinned down, make the police play their hand. If it is easy to get a warrant or secure a drug dog, then the police won’t mind doing so.

What You Can Do With Police at the Door

You have several options if the police arrive at your door and ask to come inside. You can invite the police into your home, you can decline to come to the door, and you can do practically anything and everything in between. Let's take a look at your most likely options when the police come to the door.

Invite the Police Into Your Home

Most law-abiding citizens, when faced with a request from the police to search their home, vehicle, or person, think to themselves: Why not? I've got nothing to hide. Your inner ideal citizen beams with pride; however, your criminal defense lawyer cries out in anguish.

Quite simply, you should never consent to a police search of your home. Ever. There is nothing to gain. The status quo with police at your door is that neither you nor anyone else in the home will be arrested. If you allow police inside your home, the best-case scenario is that they find nothing and, just as before, neither you nor anyone else in the home will be arrested.

Consider the following:

Police arrive at John’s home and ask to come inside and talk. John politely declines. No one gets arrested.

Police arrive at John’s home and ask to come inside and talk. John invites the officers inside. Once inside, the police ask to search the premises, which John allows. Police search the living room area and various bedrooms, but find no evidence of illegal activity. The officers thank John for his time and return to their police cruiser. John resumes his pre-visit activities. No one gets arrested.

Say it with me: there is nothing to gain.

On the other hand, there is everything to lose by consenting to a police search. As Scott Morgan, Associate Director of Flex Your Rights, thoroughly explains, a number of things can go awry when you invite the police into your home.vi If you allow police inside your home, the worse-case scenario is that they find evidence of a crime and that either you or someone else in your home will be arrested. Consider the following:

Police arrive at John’s home and ask to come inside and talk. John invites the officers inside. While inside, one officer catches an aroma of smoke and asks John for permission to search the premises. John obliges. Upstairs, in John’s son’s room, police open a lockbox and find an ounce of marijuana, rolling papers, and a digital scale. John’s son is arrested and charged with felony possession of marijuana with the intent to sell. John uses his son’s college fund, which may no longer be necessary, to pay for a high-priced criminal defense lawyer.

Police arrive at John’s home and ask to come inside and talk. John invites the officers inside. Much to John’s chagrin, one officer sees a marijuana cigarette under the couch, which had been dropped there by John’s gardener, Jimmy McPot. Jimmy had taken a break from work last week to burn one down and watch some daytime television. John tells the officers that the marijuana isn’t his, but this is something that the officers hear every single day. Nice try, John.

Don't do it. Don't ever, ever, ever consent to a police search. There is nothing to gain. Ninety-nine times out of a hundred, nothing may come of it, but the one time that a police search goes wrong could stay with you for the rest of your life.

Step Outside to Speak with the Police

If you are comfortable speaking to police, but nonetheless want to protect the privacy of your home, you can always step outside and speak with police. Whatever is outside your door, be it a stoop, a porch, or a hallway, is certainly less invasive than your own living room.

If you do step outside to speak with police, remember to close the door. Under the Plain View Doctrine, police may seize property if three conditions are met: (1) the item is in plain view of the officer; (2) the officer is lawfully present in the place where he discovered the evidence; and (3) the incriminating nature of the evidence is immediately apparent. As we discussed above, it is lawful for police to stand at your front door; therefore, police can seize any incriminating property that they observe from that position. Consider the following:

Police arrive at John’s home and ask to come inside and talk. John steps outside to speak with the police, but leaves his front door open. While speaking with John, one of the officers notices a marijuana plant sitting on the floor of an open closet inside the home. Police arrest John for possession of marijuana and subsequently search the home, which yields three additional marijuana plants and an extensive collection of Cyndi Lauper records. On the way to the police department, one of the officers quips that they would have had nothing if John had just closed his front door.

Compare the following two cases. In United States v. Peters,vii the Defendant opened his hotel room door to speak with police, but did not close the door behind him. Police looked past the Defendant and spotted a clear plastic bag with what appeared to be drugs, a razor blade, and a scale. Police immediately arrested the Defendant. The Peters Court held that the evidence was properly obtained.viii In United States v. Washington,ix the Defendant opened his hotel room door to speak with police, but closed the door behind him. Later, a second occupant exited the room and the police ordered that the door remain open. The Washington Court held that police violated the Defendant’s Fourth Amendment rights when they gained visual access to his room by refusing to let the second occupant close its door.x

What can you learn from these cases? If you go outside to speak with police, close the door behind you!

Speak to the Police Through the Door

If you are comfortable speaking with the police, but you do not want to open your front door, you are free to speak with the police through the door. You can ask for officer names, ask for identification, provide your own information, or even have a full conversation through the front door. You may feel silly, or your may even feel like a kook, but the police will remain outside your door and your constitutional rights will remain intact. Another hypothetical:

Police arrive at John’s home and ask to come inside and talk. John walks to the front door, observes the police outside, and responds through the door loud enough for the police to hear. The police inform John that they are conducting a community involvement canvas. John answers a few questions, thanks the police, and sends them on their way. No one gets arrested.

If you speak with the police through the door and still do not want the police to enter your home, just say no! It's that simple. You are well within your rights to inform police that you do not wish to speak to them at that time. Remember, knock and talks only work if they are voluntary and consensual. Once you inform the police that you do not wish to speak to them, the knock and talk is over.

Do Not Answer the Door for the Police

If the police knock on your door and ask to speak with you, but you do not want to speak to them, you are not required to answer the door. There are a number of reasons not to speak with the police. First and foremost on that list is the simple reason that you don’t have to. A common misconception in society is that citizens must speak with the police upon request. False. Untrue. Blasphemous in certain circles. You do not have to speak with the police. Spare yourself the headache— don’t.

Police arrive at John’s home. John is watching Breaking Bad. Police knock on the door. John continues watching Breaking Bad. Police peer inside the window and say they just want to talk. John opens a beer and keeps watching Breaking Bad. Police promise that they don’t want to cause any trouble and are really just out to protect innocent women and children. John makes some nachos and returns to watch Breaking Bad. No one gets arrested.

It is important to emphasize once more that you must allow police to enter the home if they have a valid search warrant. The scenario above only encompasses instances in which the police ask you to voluntarily open the door and engage in a consensual conversation.

Conclusion

If the police knock on your door and ask to speak with you, there are a number of ways you can respond. You can invite them inside, you can refuse to answer the door, and you can do just about anything and everything in between.

As is the case with several legal questions, the law varies from state to state. If you are concerned about your rights and obligations in a knock and talk, talk to a local criminal defense attorney. Additionally, state-specific law blogs may have already addressed this issue. For example, Tennessee-based attorney Joe Brandon recently published a blog post that squarely addresses whether the police can come to a house without a warrant and ask questions in the State of Tennessee.xi

In the view of this author, unless the police have a valid search warrant, there is no reason to invite the police into your home and even fewer reasons to consent to a search of your home. State your respect for those who serve and protect, but politely decline to speak. You may feel rude, but you may very well spare yourself from a legal quagmire.

NOTICE: This article is written for informative purposes only. This article is not legal advice and does not create an attorney-client relationship between the author and any reader. Readers are cautioned against relying on the information contained in this article for legal purposes. Always consult with an attorney before taking any legal action as case law and statutes frequently change.

Footnotes

i Grant Matthew Scheiner, What to do when the police show up at your house with a search warrant, Avvo Legal Guides (Nov. 17, 2013, 8:35 p.m.), http://www.avvo.com/legal-guides/ugc/what-to-do-when-the-police-show-up-at-your-house-with-a-search-warrant.

ii U.S. Const. amend. IV.

iii Davis v. United States, 327 F.2d 301 (9th Cir. 1964).

iv United States v. Johnson, 170 F.3d 708 (7th Cir. 1999) (Evans, J. concurring).

v Id. at 721.

vi Scott Morgan, 5 Reasons You Should Never Agree to a Police Search (Even if You Have Nothing to Hide), Huffington Post (Nov. 17, 2013, 8:40 p.m.), http://www.huffingtonpost.com/scott-morgan/5-reasons-you-should-neve_b_1292554.html.

vii United States v. Peters, 912 F.2d 208 (8th Cir. 1990).

viii Id. at 212.

ix United States v. Washington, 387 F.3d 1060 (9th Cir. 2004).

x Id. at 1077.

xi Joe M. Brandon, Jr., Can the Police come to my house without a warrant and ask me questions?, Murfreesboro Law Blog (Nov. 17, 2013, 8:45 p.m.), http://joebrandonlaw.com/2013/09/23/knock-and-talk/.