Is it better to be a jack of all trades or a master of one?

That’s a question humanity has debated across the ages – from LinkedIn newsfeeds to the agoras of ancient Athens.

The original argument between two Neanderthals was, “is it better to be man-who-makes-fire-very-good or man-who-makes-fire-but-is-also-hunter-and-gatherer?”

It’s a question we’ll all have to answer at some point in our lives. Specialist, or Generalist?

Those of us settling into careers will need to choose between mastering one role or trying our hand at all of ‘em. Those of us considering grad school are going to decide between building off the degrees we have or expanding our knowledge into new areas. Some of us may even find ourselves in positions where we’ll be faced with hiring specialists or generalists.

So which is it going to be? If you haven’t chosen yet, what will you choose? And if you have chosen, is it a decision you can reverse?

To answer that question, we’ll first need to understand what each one truly is.

The Generalist

The generalist is your human Swiss Army knife, making up for a lack of expertise in one area with competency in just about all of them.

In an office context, the generalist is the person who can step in for the receptionist, make a half-decent sales pitch to a customer, troubleshoot a computer, and show the new guy how to fix the copier after it jams for the eleven-billionth time that week.

They’re versatile, adaptable, resilient, and for many folks, they’re the obvious choice – particularly for Millennials.

Plenty of us still remember what an absolute nightmare it was entering the job market in the wake of the Great Recession, and those of us lucky to avoid the worst of it probably still didn’t have it easy.

After months of searching for any job (let alone a decent one) there’s a very real appeal in diversifying our skillsets as much as possible. There’s safety in generalization. Knowing something about everything gives us the ability to move from position to position or department to department, weathering cutbacks and layoffs. Should we find ourselves job searching, we’ll have a wide range of options available to us – and that’s just if things go wrong.

When it comes to leadership potential, it’s actually generalists who have the advantage over their more expert peers. Time after time after time it’s generalists who are favored for management positions – and with good reason. The simple ability to understand how each position functions and how each contribute to the company’s bottom line gives generalists unique insight and the respect of the people they’re managing.

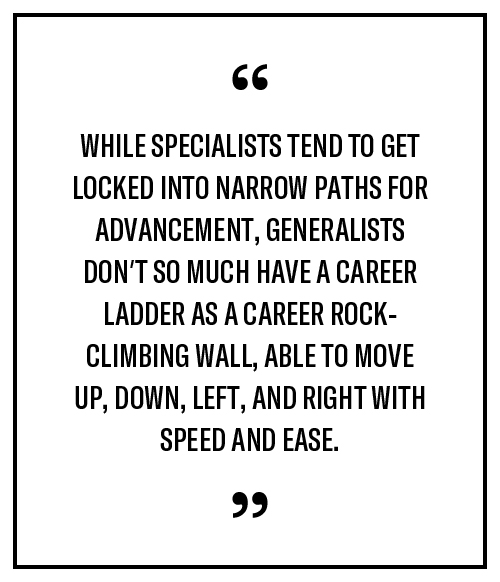

While specialists tend to get locked into narrow paths for advancement, generalists don’t so much have a career ladder as a career rock-climbing wall, able to move up, down, left, and right with speed and ease.

That freedom, however, comes with a price.

There is true danger in spreading yourself too thin. When we make ourselves stand-ins for every position, there’s a good chance a stand-in is all we’ll be used as – treated as “professional substitutes,” moved from crisis to crisis or passed whatever work nobody else can be bothered with.

While generalists are seen as potential leaders, actually proving ourselves to our superiors can be challenging. When our roles are ambiguous, our outcomes and success stories can be as well. We might be the glue holding the department together but we’ll still struggle to stand out in comparison to people with clearly defined positions and objectives.

And of course, there are times when being a jack of all trades simply doesn’t cut it. No matter how broad our knowledge might be, the harsh reality is that we are not as qualified to make a call as someone who has years of dedicated training. Surgery needs to be performed by surgeons – it’s as simple as that.

Which brings us to:

The Specialist

At its most basic, the specialist is simply someone with expert knowledge in a certain area – usually resulting from years of patient and painstaking mastery at the expense of other disciplines.

Doctors and lawyers are usually cited as examples, though this can apply to everyone from pastry chefs to network security specialists to chemical engineers working exclusively on developing superior shampoos for Jack Russel terriers. And even within those fields things can get tricky – a talented general physician is still a generalist compared to a diagnostic pathologist.

While the exact meaning might vary from context to context, the benefits to specialization are universal.

Beyond the simple thrill of being able to master something, the pay that often accompanies specialization can serve as a major incentive to specializing our skillsets. Expert knowledge means expert compensation – well into the six figures, depending on the field.

Alongside that, being an authority on a subject comes with a significant degree of respect and prestige, and the best and brightest specialists may even have an opportunity to carve out a career for themselves just offering their input on a problem or situation.

Specializations’ narrow-focus can also offer a clear and concrete plan for the future, letting us know exactly where we are now, where we want to be, and what steps we’ll need to get there – definitely a relief for folks overwhelmed by the chaos of post-college life. On that same note, there may never be a better time to specialize than right now, when we’re already in the habit of studying and researching and still young enough to handle the demands that come with it. It’s not for everyone, but damn it, if someone’s got to be affluent, influential, and respected, then why not us?

Which isn’t to say there’s no downside.

While they’ll be fewer people to compete with the more specialized we become, it will still be brutal. In any given area, there’s only going to be so many specialist positions available, and we’ll need to count on being the best candidate every single time or (and this is the far more likely option) face the possibility of having to relocate to find that niche job opening.

That might be great at first, but even the most seasoned road warrior will attest that the life wears on you after a while. Specialization also carries with it an inherent risk to balance out that potential reward, as even a slight change to the world can jeopardize our careers.

So where does that leave us? As technology, the economy, business – hell, as the whole world changes at an ever-accelerating rate, it’s never been more urgent that we answer this question. Specialist or generalist – which is it going to be?

As it turns out, it might very well be both.

T-Shaped People And The (New) Renaissance Man

Call it the “Model T.”

Or the “T-shaped” person. Or the “E-shaped” person. The “Repeating W Model”, the “Specialized generalist”, and even the “Pi-Shaped person.” The names might differ but the core is still the same: a broad base of knowledge contributing to a single point of brilliance. And that’s not just some passing management fad or a wussy non-answer to that age-old dilemma – in today’s world there’s very real need for people who are brilliant at, well, everything related to their chosen specialization.

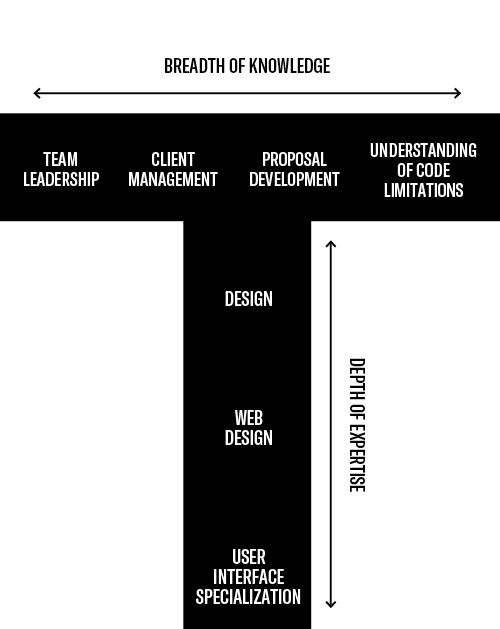

So what is T-Shaped? Imagine for a moment you’re a web designer. This T represents the sum total of your skills:

The trunk of the T is your specific job’s progression from generalist to super-specialist. You might call them your “hard skills,” like coding. The top of the T are all the many other skills you need to ascend to the top of your field. Career coaches and psychologists call many of these “soft skills” – all the other things you need to master to work effectively with others.

So how do you do it? How do you become a T-shaped person? Management coach Andrew Sobel tells a story that illustrates an iconic T-shaped industry leader, David Ogilvy, of renowned ad firm Ogilvy & Mather.

In an effort to win the coveted Rolls-Royce ad account, Ogilvy did a deep dive into Rolls’ company history, culture, and engineering. A single detail in an internal technical report popped out at him: the ticking of the dashboard clock is the loudest sound the driver can hear at 60 miles per hour.

There’s a world in that line. This single detail spoke to the quality of Rolls-Royce engineering, the luxury of its product, and its focus on the customer experience. Ogilvy won the account, and the campaign built around the quietness of the Rolls’ cabin is the reason quietness is held up as an indicator of auto quality today.

The question is, what about Ogilvy – David Ogilvy the man – enabled him to go on this odyssey of the mind and find a detail everyone else had overlooked while they were busy Don Draper’ing it up in conventional brainstorming sessions?

Two qualities: he was both a specialist and a generalist. His life until that point had prepared him as a generalist:

Like some other great client advisors such as Peter Drucker, Ogilvy practiced a number of trades—apprentice chef, stove salesman, farmer, and British intelligence agent—before settling in to become one of the greatest advertising geniuses of all time.

And his approach to being an advertising executive was that of a specialist:

Whereas many advertising professionals relied on “creative instinct” alone to develop new ideas, Ogilvy believed in carrying out in-depth research about every aspect of a company’s products, customers, and competitors.

Ogilvy wrote that a surgeon once told him, “‘…What distinguishes the great surgeon is that he knows more than other surgeons.’” He adds: “It is the same with advertising agents. The good ones know more.”

So how do you do it? You’re probably too old to join the CIA. But you’re not too old to travel the world, try another field, or enlarge your range of experiences in your current one. You can also develop these four principles we’ve distilled from studying the concept of the T-shaped man:

Four Principles of the T-Shaped Individual

- Be invested in what you’re doing. If you’re not, pivot to what you want to do most and use your current career as part of the top part of your “T” – an experience that makes you a richer, deeper generalist. It’s going to be impossible to develop yourself into a T-shaped careerist if you’re iffy on your career, but it’s also true that all experiences are opportunities for growth.

- Seek out new experiences and information in disparate fields – then make connections. How can behavioral economics radically change the car rental industry? If you’re a manager at Hertz, it could be you who answers that question (and never has to look for work again).

- Be generous with your knowledge – teach and mentor others, and seek out mentors yourself

- Learn from the T-shaped people in your life. Who do you know who is T-shaped? When you think of someone who has a genuinely cool job, is really about the job – or because they’ve made it cool by bringing a T-shaped toolkit to it?

The Road to T-Shaped

Each and every one of us is a unique combination of natural talents, curiosities, perspectives, and passions, so there’s no one road to being T-shaped. Perhaps the best way to explain it is through examples:

We’re talking about a microbiologist who uses his scientific knowledge to improve his cooking and homebrewing, both of which he’s equally passionate about.

We’re talking about a quality assurance manager who can streamline a company process and use the same principles to organize an amateur production of Hamlet and then take those performance skills back to the office to inspire the team.

We’re talking about how a nurse-in-training could use his knowledge of anatomy to improve his art, and his art as a way to memorize anatomy – it worked for Da Vinci, after all.

It might sound counterintuitive, but it’s through generalizing our knowledge that we’re able to specialize, and through specializing that we’re able to pick up new skills. The world isn’t compartmentalized – and to be T-shaped we can’t compartmentalize ourselves.

It won’t be easy, and it certainly won’t be fast, but there’s going to be nothing more rewarding – in our careers or in our lives – than cultivating the ability to discover the connections between skillsets and fields.

While the specialist-generalist debate might not ever be truly settled, perhaps there’s a more critical question we need to ask ourselves: Why settle for anything less than being all that you can be?