“Men wanted for hazardous journey. Small wages, bitter cold, long months of complete darkness, constant danger, safe return doubtful. Honour and recognition in case of success.”

Legend has it that these were the words that appeared in British newspapers in 1914. Of the some five thousand applicants who responded, a mere 28 were selected to make a hazardous expedition to the South Pole. While each and every one of these 28 could very well serve as examples of courage, toughness, and ingenuity, none encapsulated these qualities better than the man who brought them together:

Ernest Henry Shackleton.

Who He Was

Born in Ireland in 1874, Shackleton traded his modest prospects for a career in the British navy. While Shackleton quickly developed a reputation as a rambunctious, ambitious, and popular officer, the get-rich-quick schemes of his civilian career would be marked with almost constant failure. He made an unsuccessful run for office. Botched an attempt at being an entrepreneur. A career in journalism fizzled out, as did one in academia. He was on the verge of financial ruin when he threw himself into a final make-or-break expedition to Antarctica. What was to follow would be one of the most unmitigated disasters, and greatest feats of survival, in the history of exploration.

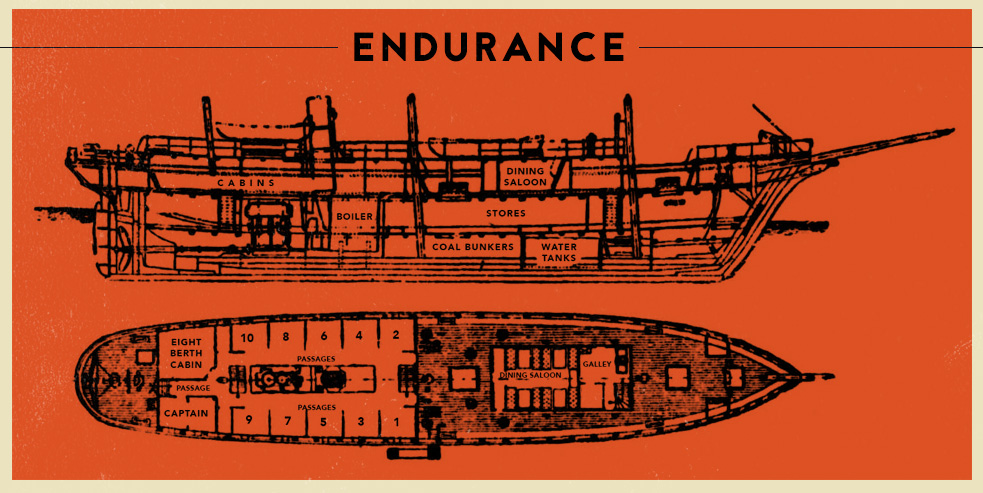

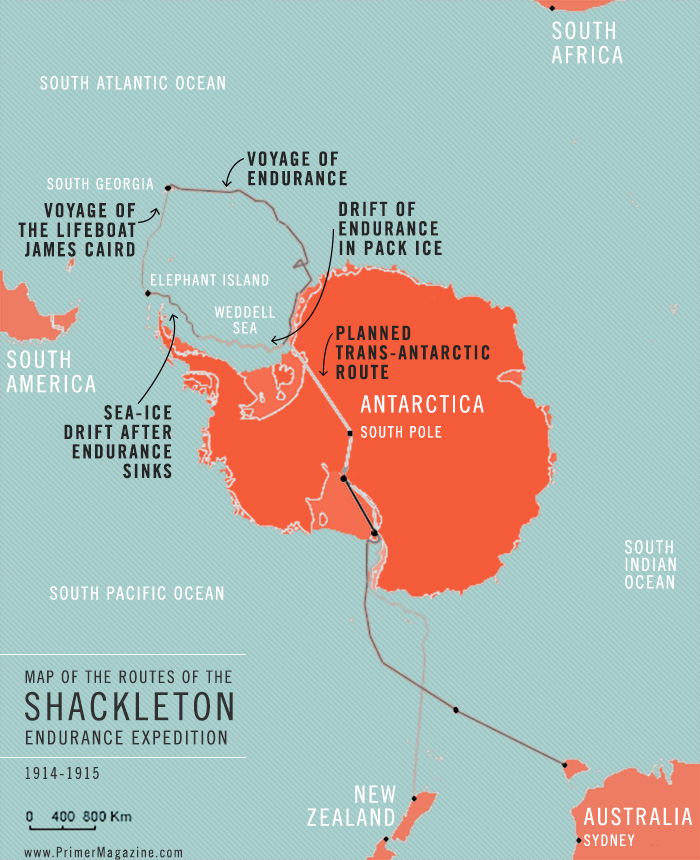

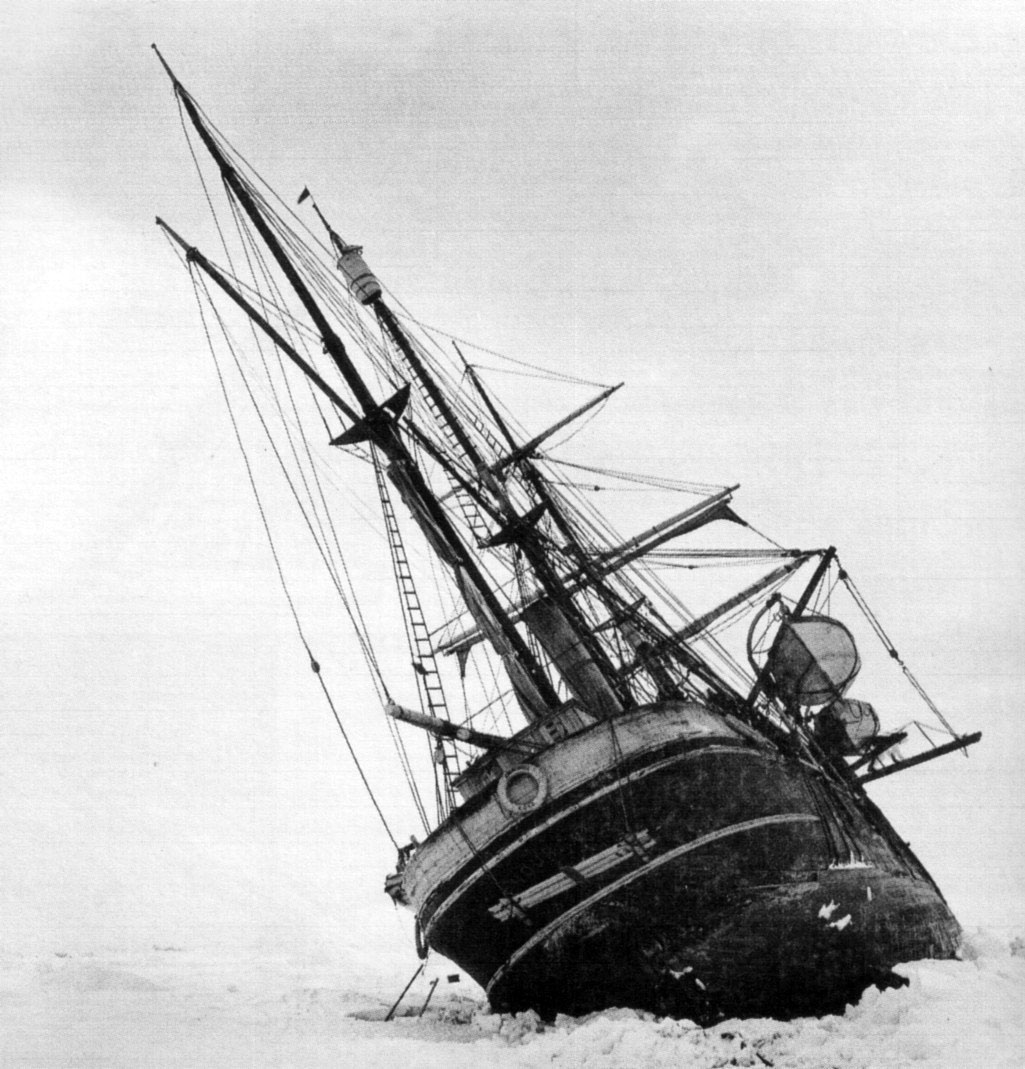

Shackleton’s barquentine The Endurance became trapped in the icefields of the Weddell Sea of Antarctica. After waiting months for a thaw, a sudden shift in the ice began to crush the hull, forcing the crew to abandon ship. Shackleton and his men found themselves stranded in the most isolated and hostile place on the face of the earth- over 1,000 miles from the nearest human being.

Endurance trapped in ice before sinking.

This is usually the point where any other man would’ve lain face down in the snow and died. Shackleton was not any other man.

Shackleton led all 28 of his crew on a harrowing march through icy hell, dragging not one but two boats behind them as they went. The journey would see them face off with frostbite, exhaustion, illness, infighting, crushing despair, and the miserable effects of a diet of seaweed and seal meat (made worse by the fact that the only “toilet paper” available came in the form of chunks of loose ice.) it would be five miserable months before the survivors of the Endurance would set foot on solid ground again- “solid ground” being in this case an equally miserable chunk of frozen rock at the edge of the continent. Think Shackleton and his crew hunkered down and waited for rescue? Think again.

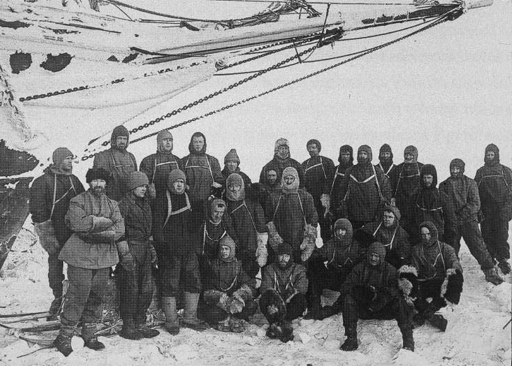

The 28 men of Endurance.

Shackleton, accompanied by the absolute worst members of his crew (those most prone to bickering and infighting), crossed yet another 800 miles of angry Atlantic Ocean (in a glorified raft, at that). Finally landing on the British island of South Georgia, Shackleton and his crew crossed a mountain that no human in history had crossed before (which was made more impressive by the fact that they had to lug their enormous cajones behind ‘em). Coming down the other side of the previously unconquered mountain range, Shackleton hailed a Chilean steamer and rode back 800 miles to rescue his men. In their two year ordeal, not a single one of them perished.

Why We Want To Be Him

It takes one mean sonuvabitch to survive in conditions as hostile those that Shackleton endured. It takes something else entirely to guide, manage, and rescue 28 men without losing a single one of ‘em.

It takes leadership, and leadership means:

Optimism

For all the hazards nature threw their way, Shackleton knew that the greatest threat to his men’s survival was themselves. With only each other to rely on, allowing even a single man to despair would unravel the entire crew and destroy any hope of escape. The solution? Keep everyone (including and especially himself) too busy to die.

Throughout their nearly two-year ordeal, Shackleton kept his men in a flurry of activity. Dog walks and races were held. Holidays, even in this miserable landscape, were still solemnly observed. Combatting boredom, keeping the crew physically and mentally sharp, and constantly focused on solving the problems that they could rather than festering over the ones they couldn’t.

The crew hauling one of the lifeboats, the James Caird, behind them.

Strategy

To claim that Shackleton invented the concept of cross-training would be a falsehood. To say that he didn’t have anything to do with it would be an utter travesty.

Under Shackleton’s direction, uneducated deckhands were trained in collecting scientific specimens. Scientists were given crash courses in medical care, and doctors and officers helped hunt for food and got their hands dirty with repairs. The result was that each and every one of the crew could, in a pinch, replace everyone else. But Shackleton’s strategy cut deeper than simple practicality. Familiarizing his crew with each other’s jobs gave the survivors a chance to walk in each other’s shoes, and the result was a much greater appreciation and understanding between the crew of the hardships and pressures placed on each other.

Organization

Shackleton’s greatest skill was, however, his intense understanding of his own crew, maintaining detailed mental notes of his crew’s skills and personalities. Shackleton was able to organize work and living assignments according to survivors he knew would get along with each other, even go so far as to house the crew’s most pessimistic and ill-tempered members with himself to keep them from demoralizing the rest of the crew. A fantastic delegator, Shackleton ensured that he left his most capable crewmen to command the survivors of Elephant Island during the final bid for rescue in 1916.

“Honour and recognition” were not waiting for Shackleton and his crew upon their return to Britain. Consumed by the first world war, the news of the incredible journey of the Endurance barely made the papers. Shackleton himself would die of a heart attack on a final voyage, but his passing was to be mourned by his crew, most of whom had signed up for yet another expedition under his command. He remains, even a century later, a remarkable example of courage in the face of unimaginable adversity. Shackleton’s heroic command offers us a model for the kind of leader, the kind of man, we should all aspire to be.

To Learn More About Shackleton:

Endurance: Shackleton’s Incredible Voyage – By Alfred Lansing

Shackleton: By Endurance We Conquer – By Michael Smith

Shackleton: His Antarctic Writings – By Christopher Ralling